The importance of AP African American Studies

REWRITING HISTORY: The new AP African American studies course that was recently passed has already been stripped of much of the topics in the original curriculum due to conservative backlash.

March 2, 2023

Historical merit and thought-provoking content is always the educational objective of history courses—except for when it comes to black history, apparently. There is often little for black students to identify with in most history curriculums; important eras of black history are often glossed over, invalidating black students and failing to accurately reflect their contributions to American history.

To alleviate this issue, a new AP African American Studies course was recently passed by the College Board featuring a curriculum that provided a deep exploration of African American history in America, including the origins of the African Diaspora, in-depth lessons on the speeches of the Black Panther Party and insight on black expression through art.

But, in a time where classrooms are already being restricted from covering “controversial” topics like gender and racism, the course quickly became a vehicle for an overblown political debate.

“That’s the wrong side of the line for Florida standards…We believe in teaching kids facts and how to think, but we don’t believe they should have an agenda imposed on them,” Florida governor Republican Ron DeSantis said in a response to the course. “We believe in education, not indoctrination.”

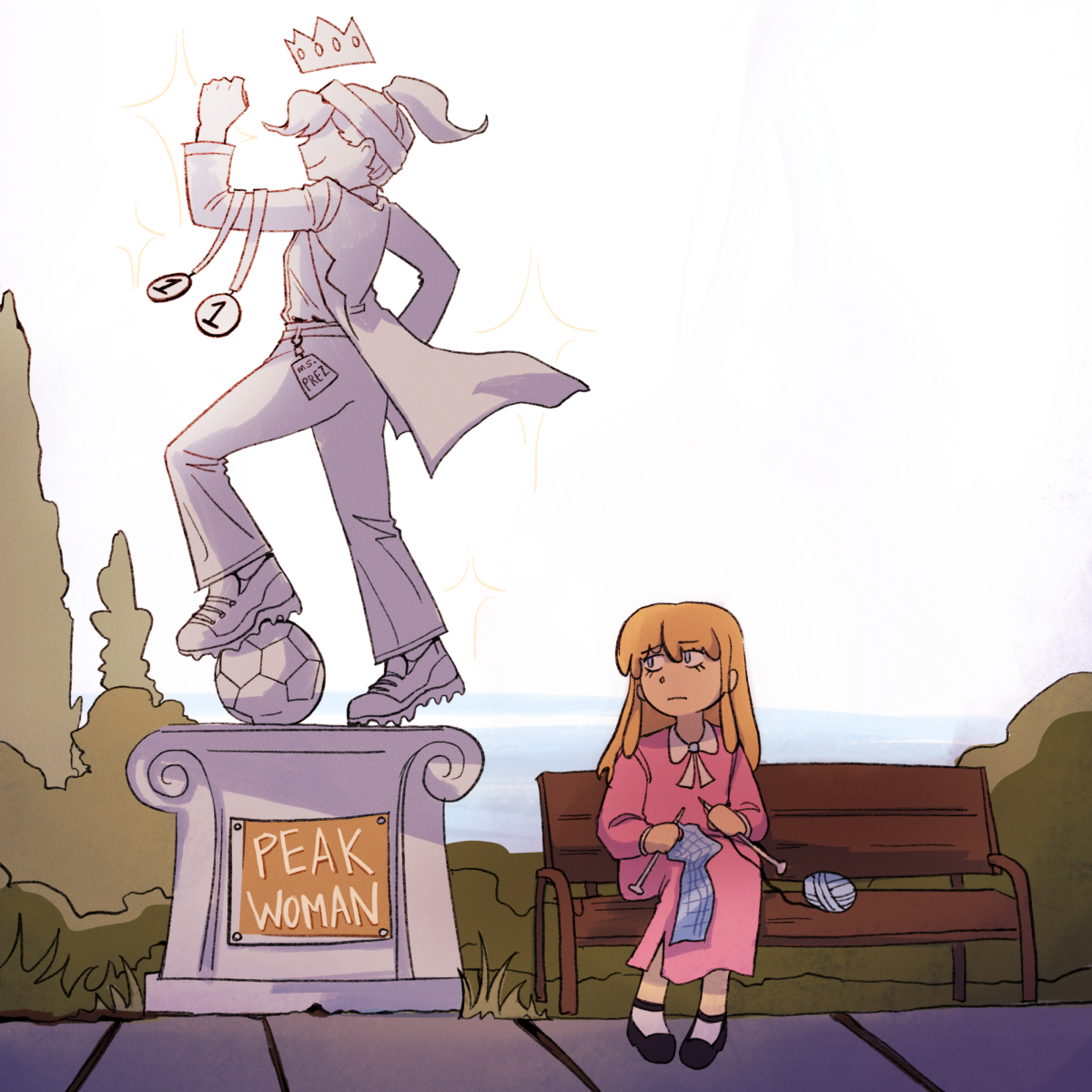

After the recent conservative backlash, the course has already been severely modified and stripped of much of the topics central to the curriculum, such as various black freedom movements and discussions on contemporary debates. However, not only is it important that the College Board offers this course to students, but that it is offered with the full educational merit and value that it was originally intended to have, rather than offering a barebones but “palatable” course.

Opponents to the course like DeSantis claim that it “lacks educational value” and violates established laws that restrict the teaching of critical race theory and other “woke” ideas. Yet the educational laws in these states provide biased portrayals of slavery and fail to devote enough time to significant eras in black history like the Reconstruction era, ultimately perpetuating the ignorance of black contributions in America and the lack of representation of black students.

According to a report by the Zinn Education Project, state standards for teaching Reconstruction “encourage classroom teachers to either rush through Reconstruction or skip it entirely” which ultimately leaves students “unaware of Reconstruction’s significance and unprepared to confront the nation’s realities.”

When such inadequacies exist, we have to realize that this controversy is just the center of a culture war in America that has unnecessarily served to fuel political agendas. At what point do we realize that calling an education about African Americans “indoctrination” is just another excuse to maintain the Euro-centric education system and invalidate the background of millions of students?

“The move to censor topics like intersectionality, the movement for Black lives, and reparations is nothing more than an assault on African-American history and worldviews—effectively whitesplaining topics that are integral to the development of American history, culture, and identity,” Ivory Toldson, director of education innovation and research for the NAACP, said.

The College Board’s job is to make sure that this course is educationally rigorous and complete despite all the political discourse. Yet, they continue to succumb to pressure and avoid talking about “controversial” topics, even though it’s not possible to create a course about the history of African Americans in America without addressing racism and its legacy. In actuality, the very merit of this course comes from the educational value from learning about, centering discussion around and directly addressing the inextricable tie between racism and American history. But from the way conservatives like DeSantis have framed their ideal history classes, it’s not possible for students to be exposed to these issues.

“You learn all the basics about the great figures, and you know, I view it as American history. I don’t view it as separate history,” DeSantis said. “We have history in lots of different shapes and sizes, people that have participated to make the country great, people that have stood up when it wasn’t easy and they all deserve to be taught.”

But we have to realize that even if we acknowledge that black history is American history, current U.S. history courses don’t have the time to highlight important black figures in history in a way that a dedicated African American studies course can. How often are students exposed to lesser known black activists? Or the origins of black poetry and art? The nuance and the pride that can be explored in this class is simply not possible in that traditional history class.

Either regular high school history has to be completely revamped or laws that restrict covering “problematic” topics have to be modified—because when a single course that covers African Americans launches such a massive controversy, it’s clear that the education system has continued to idealize American history and push African Americans to the side.

African American history is not something that should be hidden or covered up—not only to acknowledge the flaws of America, but also to give black students some sense of pride and belonging in the history books that often prioritize the white narrative.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)