The “Clean” Girl trend is WOC Culture

THE DIRTY TRUTH: By ignoring the shame WOC have endured for wearing these same features, this “effortless” aesthetic, that draws inspiration from WOC culture, has brought to attention that society has equated “clean” to fair skin.

October 3, 2022

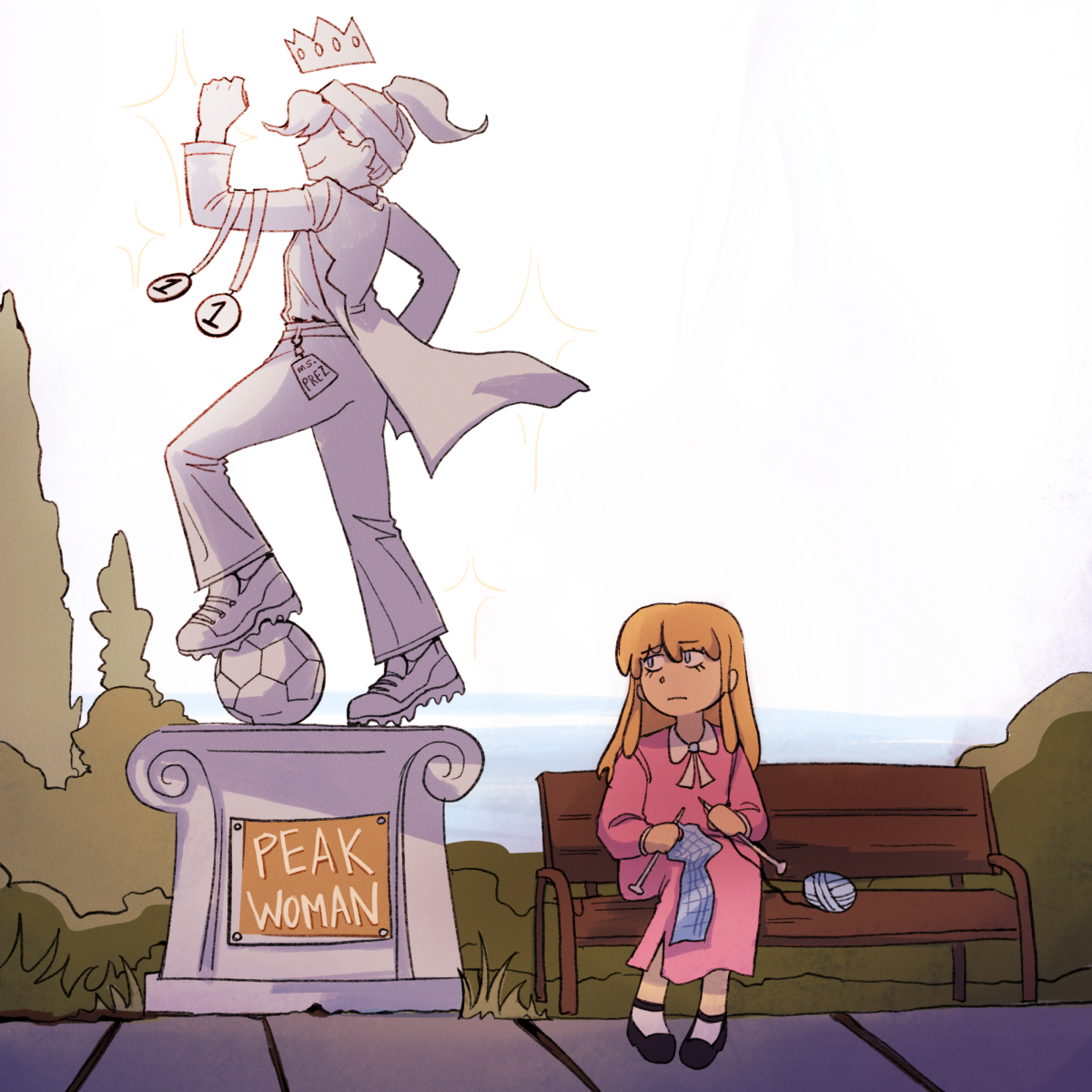

The slicked-back hair, the gold hoops and the minimalist makeup with clear lip gloss—all defining characteristics of the recently popularized “clean girl” aesthetic. But the truth of the matter is that these features have been around for decades, originating from minority groups that were ridiculed for them.

The “clean girl” aesthetic is essentially a rebranded version of Black and Brown culture. White influencers who sport these characteristics are now considered trendy, innovative and put-together. But a decade ago, these same features were admonished among minority groups.

To talk about why the “clean girl” aesthetic is problematic, it is important to clarify the difference between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. Cultural appreciation is the practice of recognizing the culture’s unique identity and culture while actively seeking to learn about the culture. Cultural appropriation is when a group or individual selectively chooses an aspect of a culture to adopt and uses it solely for personal gain, all while ignoring the significance of the culture and failing to give credit to the culture.

The “clean girl” aesthetic appropriates the culture of women of color. Before, the features of the “clean girl” trend were associated with being “ghetto and dirty” rather than “clean and classy,” since women sporting these looks were WOC. For instance, gold jewelry—specifically gold hoops—has gone from “ghetto” to “clean.” Once high fashion designers, like Marc Jacobs, started showcasing gold hoops on their runways and re-labeled them as a new trend with a new high fashion name, all of a sudden gold hoops were no longer seen as “ghetto”.

“This is about how WOC can’t wear their own style and culture because they are looked down upon when they do so,” Alegria Martinez, Latinx activist, explained to i-D magazine, a UK fashion magazine. “But on the other hand, white females are allowed to appropriate the fashion when it is beneficial to them or makes them look edgy.”

Now that these defining characteristics have been rebranded by white women, it’s considered clean and classy, upholding the norm that only a select group can actually fit into this aesthetic. Not long ago, women of color, specifically Brown girls, would be mocked for oiling their hair, a traditional Indian practice. Now, this South Asian practice has been popularized and rebranded as “hair slugging,” with white influencers taking credit for this “innovative” idea and treating it as a rare discovery.

Another example of rebranded WOC culture would be the recent trend of “brownie glazed lip”, a practice people of color have been doing for decades. The idea of lining one’s lips with a darker lip liner has now been credited to Hailey Bieber, even though hispanic women have done this to compliment their hyperpigmentation, a feature often seen in WOC.

The trend reinforces the “white people are clean” mentality, as shown by people’s refusal to attribute the trend to Black and Brown culture while openly accepting the aesthetic when it is done by white women.

Under the umbrella of the “clean girl” aesthetic, there has also been a new emphasis on self-care. This new emphasis on taking care of oneself, both mentally and physically, is a good thing. Taking care of one’s skin and hair, replenishing one’s body with nutritious foods and even just making mental health a priority are all positive aspects of the “clean girl” or “that girl,” aesthetic.

But as mentioned before, under this aesthetic, aspects of WOC culture have been rebranded as a “new trend” rather than recognizing the historical significance of these practices. It’s great that these trends are now being appreciated but it is important to give credit to the women who have pioneered these trends.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)