Northwood High School senior named a 2022 Regeneron Scholar

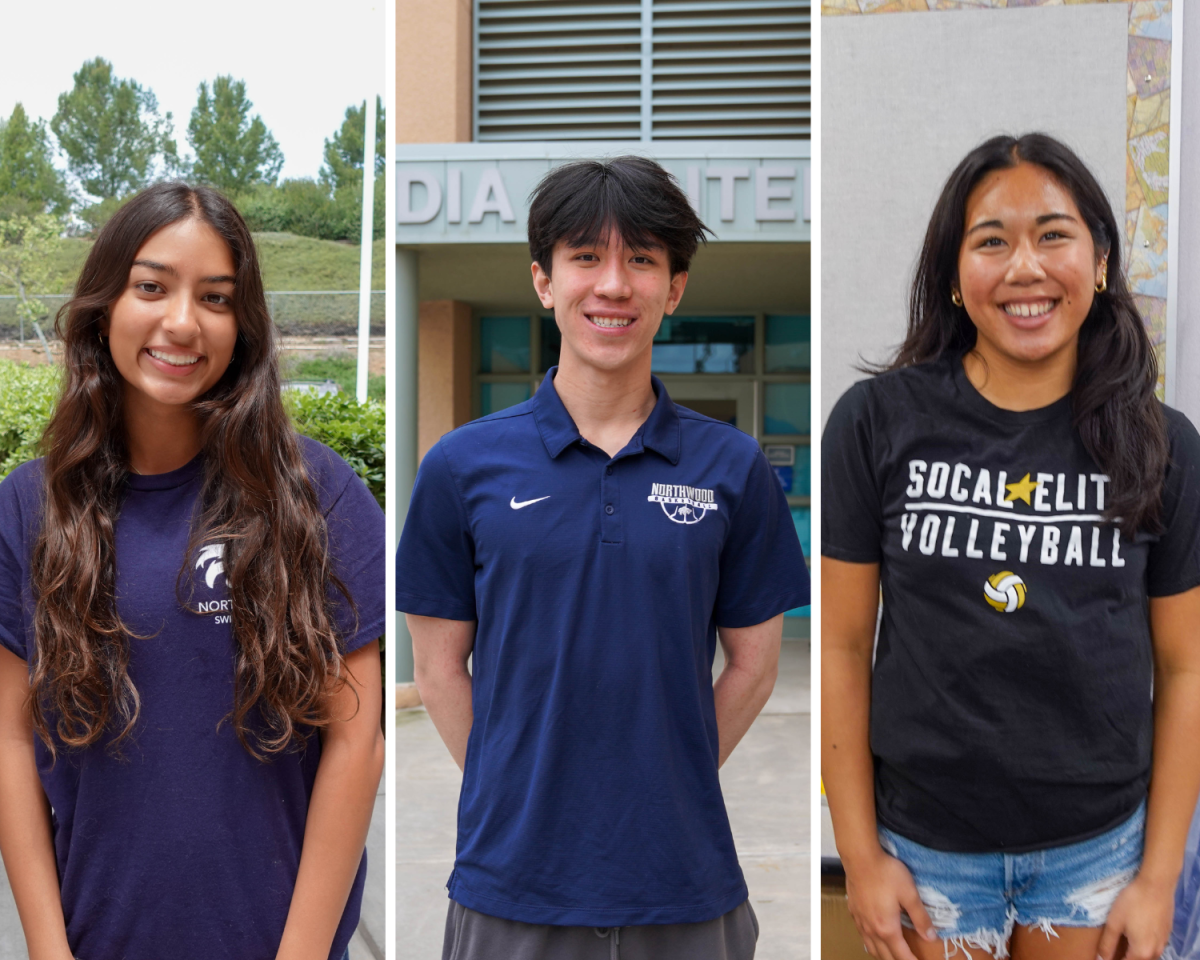

Senior Nithin Parasarthy was named a Regeneron Scholar finalist, the nation’s oldest and most prestigious science and math competition, with alumni ranging from Nobel Prize winners to founders of STEM-based companies.

After a competitive application process including both a research abstract and various personal essays, finalists were chosen last January based on their projects’ rigor and potential for growth as a world-renowned scientist. Each of the 300 scholars will receive $2,000 for their school.

“I went in hoping for the best but expecting the worst,” Parthasarathy said. “I was well aware of how competitive STS is, and even if I wasn’t selected, I knew that it was just a way for me to summarize all my findings. Of course, I was pleasantly surprised when I received the notification that I had been selected.”

Parthasarathy began his research journey all the way back in his freshman year, taking inspiration from his grandmother.

“She used to be really good at using technology, but after she took a fall, she wasn’t as adept anymore,” Parthasarathy said. “I wanted to change that.”

After reaching out to the UCLA Department of Radiology, Parthasarathy was able to obtain data from patients at local hospitals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, a neurodegenerative disorder affecting nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that causes loss of muscle control. His work helped to provide ways for ALS patients to communicate based on brain-computer interfaces, which analyze brain signals and translate them into commands on an output device.

“Whenever my parents and I would go on road trips, we’d play a lot of word games, like crossword puzzles and Around the World,” Parthasarathy said. “So I thought I could integrate my love for linguistics through developing these language models.”

The patient would be presented with a computer screen while wearing an electrode cap that could detect their brain signals through an Electroencephalogram, a test that records brain wave activity. While the screen flashed characters in front of a patient, the cap would record whether their brain had increased activity based on wave frequency. Parthasarathy’s software used probabilities of letter combinations such as “pa” being more likely than “ph” to determine ways for the patient to spell faster by predicting what the next letters would be.

Later, he applied this work to ADHD patients, finally creating the project that he submitted to the Talent Search titled “Minimally Calibrated High Performance Communication Interfaces for the Neurologically Impaired: New Directions Using Language Models Along With Gaming Extensions to Assist ADHD Subjects.”

Essentially, his project uses the same brain-computer interface setup to detect when the brain signals falter, indicating that the subject has lost focus, and play a sound to get them back on track. His conclusions helped ADHD patients focus and communicate more efficiently.

“The idea just kind of came to me after I was playing a game one day,” Parthasarathy said. “Even though ALS is extremely important because of how debilitating it is, ADHD can also be an interference with daily life as it can be hard to study or pay attention in class, and I wanted to use my work to help people with all sorts of neurological disorders.”

In the future, Partharsarathy hopes to continue pursuing research at UCI and possibly get his master’s or doctoral degree.

While Parthasarathy’s work may seem inaccessible or beyond reach, he believes that anyone is capable of doing research.

“Find something that you’re willing to dedicate the next several years to work on, be willing to spend lots of time and frustrated nights of not getting results, and just go for it,” Parthasarathy said.

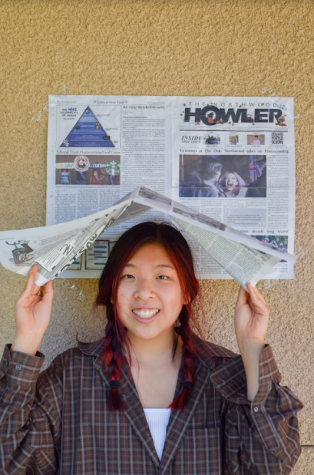

Annabel Tiong is a Northwood senior and Junk Editor for The Howler. She holds...

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)