Analyzing Squid Game: A down-to-earth reflection of human nature and capitalism

MOMENT OF FRIENDSHIP: In one of the only hopeful scenes of the series “Squid Game,” players Sae-byeok and Ji-yeong play a round of marbles after spending time sharing their life stories.

November 2, 2021

A black and white, slow-motion video of kids running on the dirt floor fills the screen as the voice of Seung Gi-Hun (Lee Jung-Jae) explains how they played the squid game as children. Behind the violence of Netflix’s “Squid Game”, there is a story about human nature and capitalism. Rather than taking a didactic stance in the development of this series, the creators highlighted empathetic and approachable characters.

In short, 456 people are given the chance to earn 45.6 billion Korean won (39 million US dollars) if they win six Korean childhood games, but unbeknownst to the participants, losing comes with deadly consequences. The straightforward nature of these games, such as tug of war or a Korean version of Red Light, Green Light, allows viewers to focus on the characters and storyline instead.

“People are attracted by the irony that hopeless grownups risk their lives to win a kids’ game,” Squid Game director Hwang Dong-hyuk said in an interview with the Yonhap News Agency.

The games along with the pastel-colored sets juxtaposed the sound of the gunshots and the bursts of blood that smeared the green jumpsuits. The layer of nostalgia added by sets resembling playgrounds, theaters and Korean neighborhoods was not only thought provoking but seamlessly incorporated the larger meaning behind the series. Viewers have tried to find hidden symbols, and several interviews were conducted with Art Director Chae Kyoung-sun who designed the sets.

“The sets in general, were created to cause confusion and chaos among the players—between reality and fiction,” Chae said in an interview with the Korea JoongAng Daily. “For example, in ‘Red Light, Green Light,’ I deliberately put a tree without any leaves behind the Young-hee robot to imply that this place was ‘lifeless.’”

Besides the cheerful set, the greatest differences when comparing the show to popular dystopian series such as “Hunger Games” or “Maze Runner” are the realistic characters and their willingness to join the game.

All the characters had unresolvable situations that forced them to play the game. Whether it be Gi-Hun, the desperate father who gambles money, or Abdul Ali (Anupam Tripathi), an immigrant from Pakistan who faces racial discrimination in the workforce, the characters have stories that resonate with viewers. While I questioned why most of these characters returned to the game when given the chance to live their normal lives, I could not help but empathize with their decision.

The performances by the actors considerably heightened the tension and emotions. Though the cast included veteran actors such as Lee Jung-Jae and Park Hae Soo, the unfamiliar actors successfully made characters, such as Sae-byeok or Ali, more relatable. Despite the commendable acting on the players’ side, the non-Korean cast members who played VIPs who spectate the games came under heavy criticism. According to The Guardian, some of these actors recently responded, explaining they were not given a lot of context before filming and struggled with the awkwardness of reciting lines with a mask on, but their excuses were not enough to justify exaggerated acting.

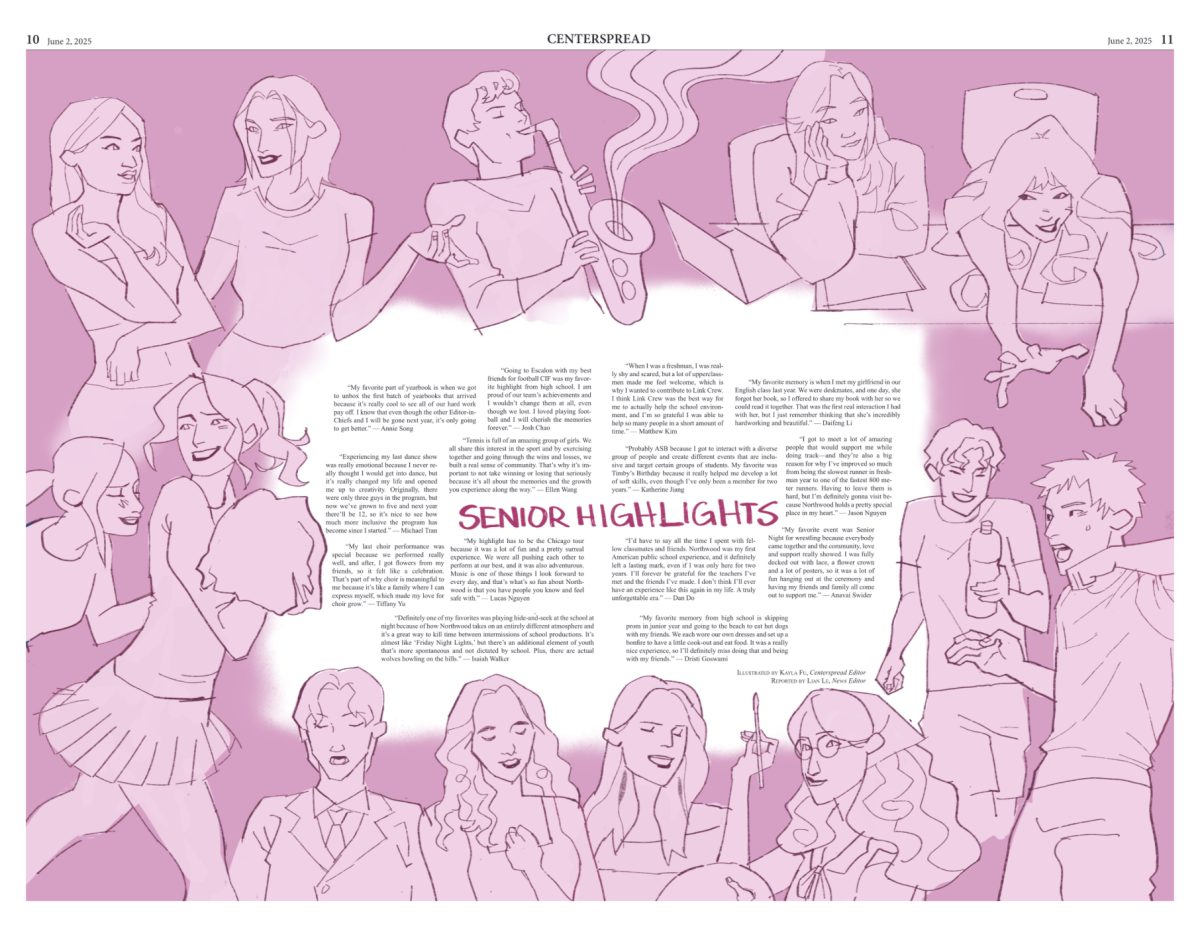

In the fourth game, characters Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) and Ji-yeong (Lee Yoo-mi) spend time getting to know each other before Ji-yeong sacrifices her life, telling Sae-byeok that she has no reason to live while Sae-byeok does. While these moments of friendship are hopeful, the selfishness of characters like Cho Sang-Woo (Park Hae Soo) are more realistic and hint at the inevitability of immoral actions in capitalist societies, which are heavily critiqued throughout the show.

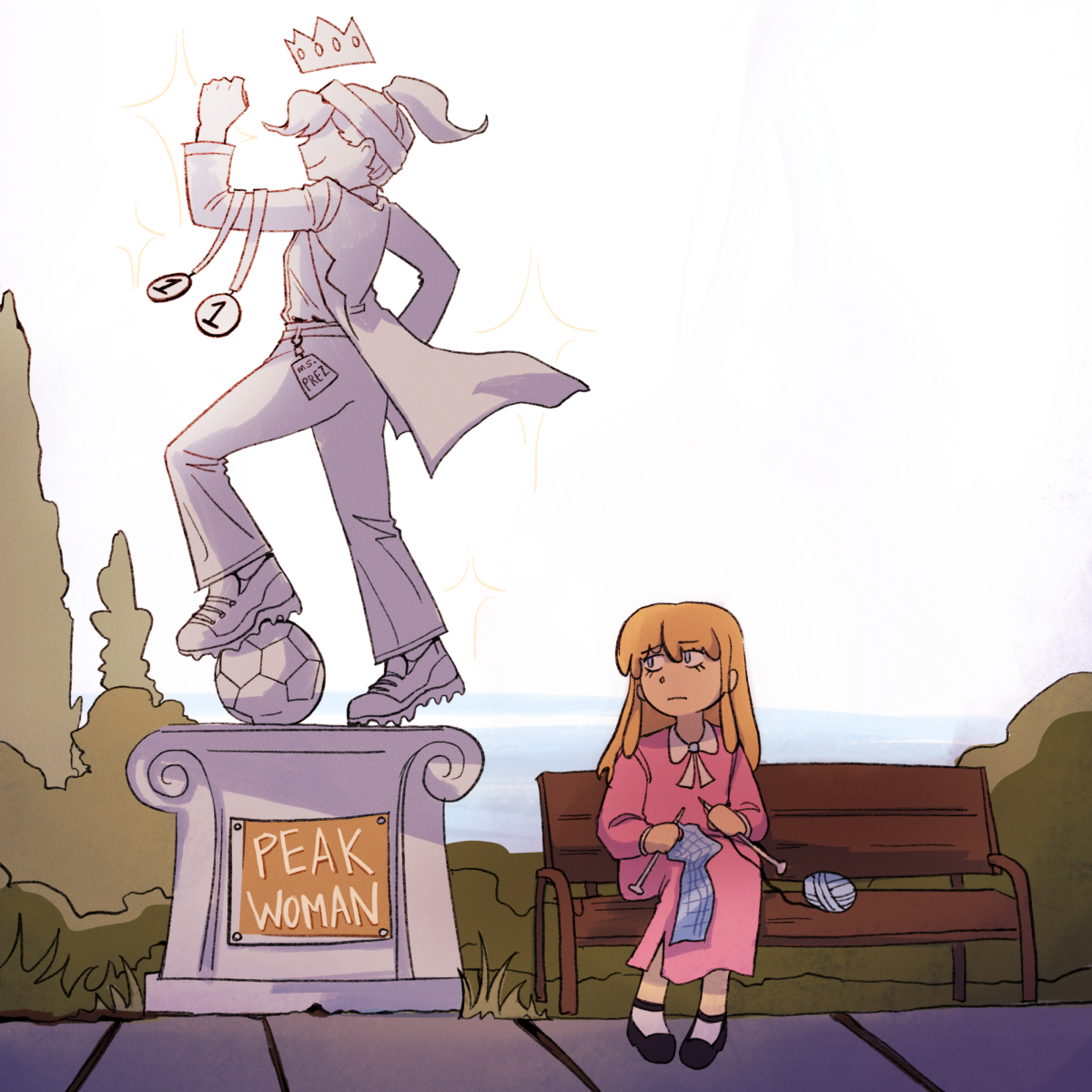

The game represents how far people are willing to go for money and all the problems the characters could not solve because of a lack of money. However, “Squid Game” also comments on how even if the gap between society’s richest and poorest person widens, both can be unhappy and lose the agency to live. The players in the game are miserable and the creator of the game, a rich, old man with a brain tumor, chooses to entertain himself by watching people kill others because he has nothing better to do.

Similar to gaining wealth in a capitalist society, while some games such as the tug of war can be won through logic and strategy, others, such as choosing the dalgona shape, are only determined by pure luck. No matter how hard they try, players cannot easily win all six games, which parallels the situation in Korean society where it is nearly impossible to climb the social ladder. While many people in the United States believe in the “American dream” or social mobility, after the financial crisis in Korea in the late 1990s, people rarely succeed financially while the wealthy grow richer.

The injustices of capitalism are further emphasized when those who won the Squid Game in previous years choose to continue recruiting members, showing how these flaws are unlikely to change.

While I was disappointed by inaccurate English dubs and subtitles, which sometimes changed the meaning of nuanced scenes, the series as a whole presents a coherent message about capitalism and its people whose lives are determined by the luck of a game. “Squid Game” was worth the chills as it challenges viewers to address society’s flaws.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)