Managing mental health at Northwood

October 1, 2021

From constant pressure to emerge victorious inside the classrooms to time-crushing extracurriculars outside the classroom, high school is a bumpy ride—but what makes it bumpier is when it is made difficult for students to find the resources and guidance they need and deserve.

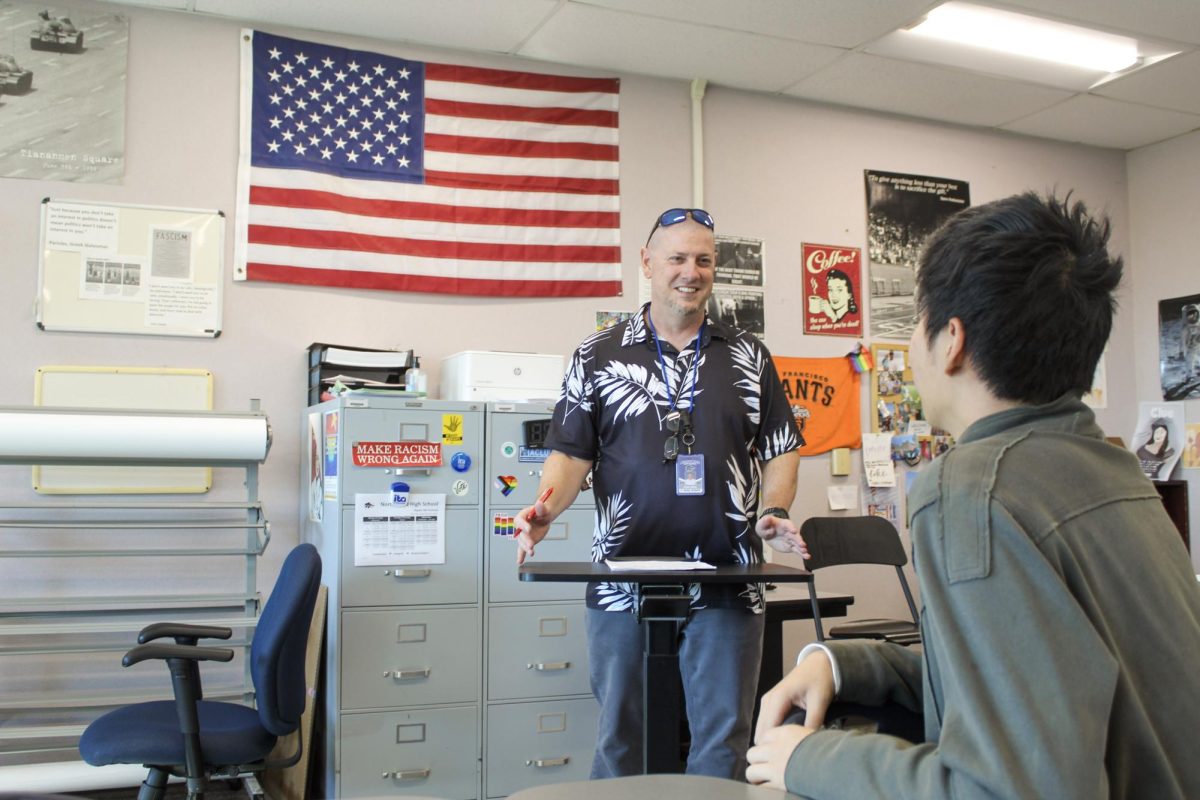

The American School Counselor Association states that the job of counselors is not only to address students’ academic needs but also “provide counseling and crisis intervention focused on mental health or situational concerns such as grief or difficult transitions.” Most counselors are trained to serve these purposes in theory, but aren’t given a chance to do so in practice. The problems are two-fold: low publicity and a perceived lack of approachability.

During my four years at Northwood, I have perceived the counseling department as a place to go for schedule changes and advice on how many sciences to take before graduation, rather than a place to visit to rant about stresses from home, vent about feeling targeted for the color of their skin or confide in a trustworthy adult about periods of self-doubt that just don’t seem to go away.

This isn’t to say that our counselors, who are patient enough to spend long hours answering questions to alleviate our academic stresses, don’t serve this function in some instances or that they aren’t prepared to—it’s simply that the department’s attempts at publicity haven’t been effective. And students are equally to blame for this, because we do not actively seek out these resources. But increasing the visibility of programs like the Irvine Family Resource Center, or increasing talks by experienced wellness coordinators like Northwood’s Megan Keller would solve this problem, and shed light on different sources of assistance.

Additionally, a lack of regular, private interaction between students and counselors formalizes the tone of our visits. Our counselors are strangers, for the most part, professional strangers who are kind and accomplished, but strangers nonetheless because we are given few opportunities to get to know them. There are solutions to this: decreasing the student to counselor ratio, increasing the frequency of student conferences with mental wellness coordinators and increasing publicity of mental health related guidance.

The counseling department has made efforts to increase publicity by plastering posters in front of classrooms and notifying advisement classes—efforts that students may not be fully aware of.

“Just recently, we pasted ‘Meet your Counselor’ flyers with a QR code,” Kim said. “We also asked TAs to advertise it.”

Resources exist: the flyers, the mental health well and the consistent flow of posts related to mental health on the counseling Instagram page are testaments to this. It’s the engagement that is low. While it is difficult to determine how many students are actually engaging with the posters, with a little help from admin through daily announcements during advisement (over the loudspeaker, so it cannot be missed) or from the district through fundraising opportunities, this number could go up.

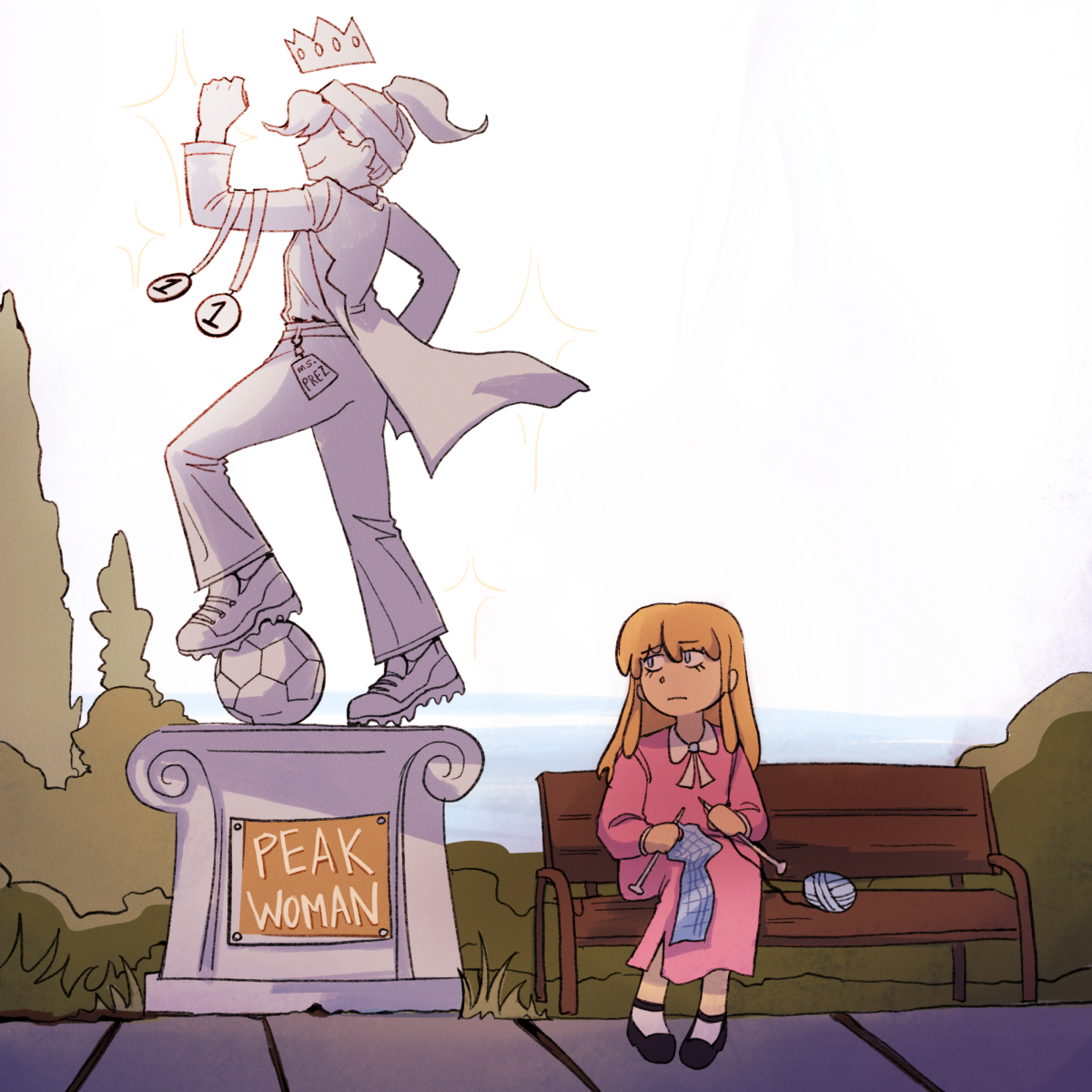

The problem does not lie at the feet of the counseling department, but in the culture which we have all cultivated. Students’ priorities are skewed. To many students, the way counselors or teachers perceive them is seemingly more important than their own mental wellbeing. It makes sense, though. Society—and specifically our city’s over-competitive educational environment—has led students to believe that the college admissions process is life or death. And studies back this up. An article titled “We’re sacrificing our kids’ mental health to the college admission industrial complex” by Bill McGarvey, claims the high levels of stress and anxiety amongst students are a result of economic fears ingrained in them by society. And our counselors have observed this phenomenon too.

“In my experience, parents and students are worried that reaching out about mental health issues will reflect on their college transcript, which is not true at all,” Kim said. “Seeking help for mental health is no different from seeking help from any other medical injury, such as a broken leg.”

According to Professor Robert Anthony Seigel from North Carolina Wilmington, there exists “an almost mystical faith in name-brand universities as a ticket to security,” and the race to the finish line is “a response to a world that is increasingly uncertain and scary—a winner-take-all kind of world.” In this high-stakes world, how many students would risk sharing the darkest and most painful aspects of their life with the same person who will send a letter of recommendation to their dream school two years from now, or with the teachers they interact within the classroom every Tuesday—afraid to be confronted by pitiful stares or to be viewed as fragile? Especially when they want to appear resilient and put together, in an effort to embody the qualities that they’ve been told are conducive to economic success.

It is our job as a community to dispel these perceptions and reaffirm students’ beliefs that their stories are worth telling, and mental health organizations such as Crossroads Initiative are doing just that. Portola High School senior Shailee Sankhala, the founder and president of the organization, kick-started it during the COVID-19 pandemic to increase awareness about mental health issues and make reformations in mental health counseling at IUSD. With over 50 members, the organization is one of the largest student-led programs in Irvine.

We don’t all have to do what Sankhala did. Prioritizing our mental health and the mental health of others above our ambitions from time to time, donating to mental health organizations and signing petitions to make changes to the parts of the education system that fail to tackle mental health effectively would have a significant impact too; an impact we all have the power to make.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)