CDA Section 230: The future of politics on social media

February 12, 2021

Immediately following the U.S. Capitol incursion on Jan. 6, former President Donald Trump faced suspensions across multiple social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat for sharing misleading content and inciting violence. In addition, Twitter purged more than 70,000 accounts associated with far-right conspiracy QAnon. These suspensions have sparked heated debate about freedom of speech and censorship; however, liberty and regulation are not mutually exclusive, and the digital world has opened up new horizons that require a balance of the two.

Following the bans, many conservatives turned to an alternative site, Parler, and essentially transformed it into a right-wing echo chamber. Parler was then disabled as Amazon Web Services removed the site from its hosting service due to Parler’s ineffective moderation of content threatening public safety; And in Parler’s subsequent lawsuit against Amazon, Amazon invoked Section 230 as a liability shield for its platform moderation.

“The fact that a CEO can pull the plug on POTUS’s loudspeaker without any checks and balances is perplexing,” European Union Commissioner Thierry Breton said. “It is not only confirmation of the power of these platforms, but it also displays deep weaknesses in the way our society is organized in the digital space.”

Section 230 has come under fire recently as Trump, Biden and even tech companies themselves call to modify the legislation. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act states, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider,” which means internet companies—such as Instagram, Facebook and Youtube—cannot be sued for the content users post on their sites nor good faith efforts to remove content that violates their policies. This leaves companies to regulate themselves, but it does not protect platforms in criminal cases, such as copyright claims and human trafficking.

In retrospect, the law has been salient in shaping the internet as we know it today. It has allowed startups to enter the online markets without liability risks and brought social media to the forefront of communication in our society.

“CDA 230 is perhaps the most influential law to protect the kind of innovation that has allowed the Internet to thrive since 1996,” the Electronic Frontier Foundation said.

Repealing this protection altogether—an approach both Trump and Biden have favored—would be nonsensical, as it would dramatically increase censorship to avoid potential lawsuits, which may also involve pre-screening all content and micromanaging users. However, this 1996 regulation is largely outdated.

One point of contention is the inconsistency of censorship: Senator Ted Cruz and other Republicans have alleged that political censorship is more prevalent on the right, but there is no evidence to corroborate this as of now.

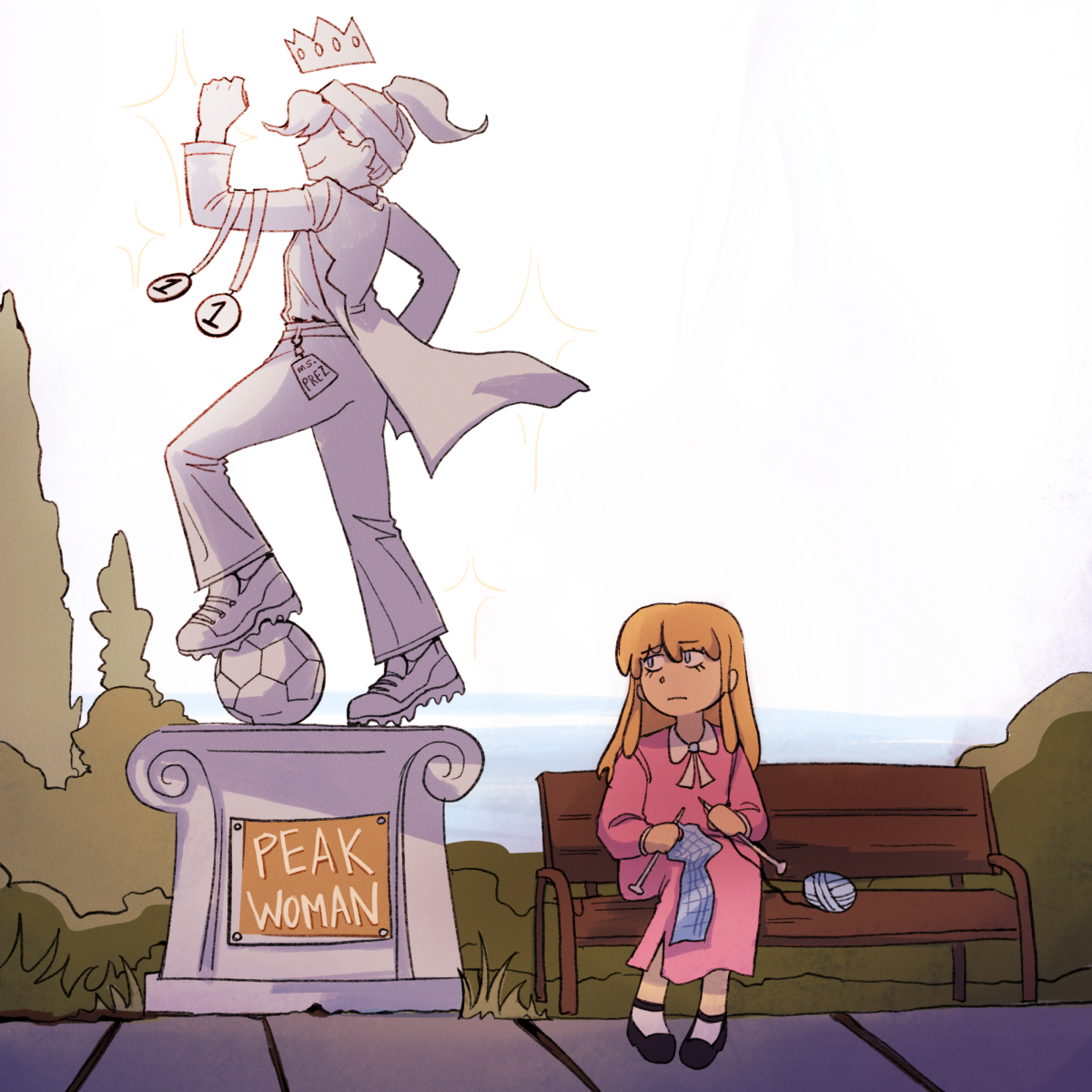

The main issue focuses on tech companies holding contradictory roles as both open-source platforms and selective publishers, as intervening with political speech online as “publishers” has now put them at risk of losing the “platform” protections granted by Section 230. However, the role of social media has never been one or the other, but rather, something in between. Since private companies have been able to restrict speech as they choose, tech companies taking an “editorial” role to moderate content is not new.

Companies uphold their terms of service that prohibits hateful conduct, which covers terrorism and violent extremism, and Section 230 legally protects them to do so. Historically, Twitter has deplatformed ISIS and other international terrorist groups for recruiting members and organizing violence on their platforms, and Youtube and Spotify censored conspiracy theorist Alex Jones in 2018 for violating their hate-speech policies.

To a lesser degree, Trump infringed on speech policies when inflaming domestic terrorism and broadcasting false claims about election fraud to his millions of followers, which resulted in his ban. The surge on the capital and consequent Trump ban have been described as the “9/11 moment of social media” by Breton and a “turning point in the battle for control over digital speech” by Edward Snowden, an exiled American whistleblower. While it is important to not resort to a Patriot Act-equivalent crackdown on civil liberties, recent events have clearly demonstrated the need to address the faulty underpinnings of social media and its crossroads with free speech.

Deciding what violates their policies and whether they should be allowed to censor content at all are gray areas. Handing the government or tech companies the power to form policies and make censorship decisions on essential platforms sounds worryingly technocratic, yet an overly populist space without moderation would perpetuate the amplification of misinformation, hate speech, conspiracy theories, organizations of violence, etc.

Nonetheless, social media has created a digital breeding ground for polarization and radicalization, and thus, should be legally held accountable to take nonpartisan preventative measures and be transparent about their moderation. Moving forward, some proposals from U.S. legislators to change Section 230 have been to remove protections from certain categories of content and to only offer liability protection after meeting certain standards set by the government. Uncertainties for Section 230 lie ahead in the Biden administration as it remains without a clear modification plan, and more importantly, our laws have yet to catch up with innovation.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)