Integrated Science works toward the future

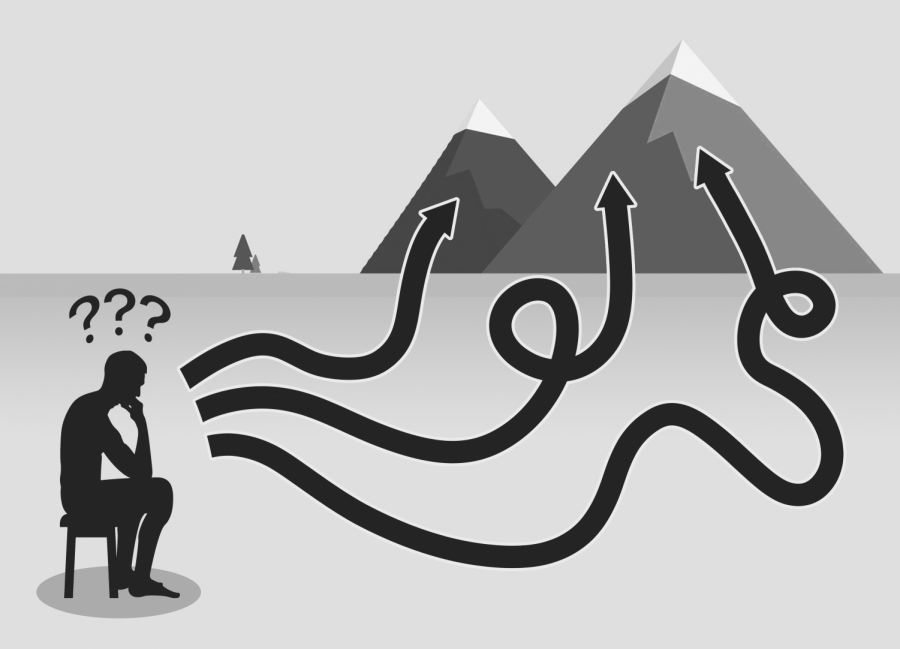

PERSPECTIVE: Learning is a nonlinear process.

February 13, 2020

A mixture of sounds can be heard across the room: student discussion, fans whirring, pencils scratching on notebooks, scissors cutting wood, questions followed by comfortable pauses. Today the Integrated Science (IS) 3 class is wrapping up their experimentation regarding optimal wind turbine design, analyzing various factors involved in the efficiency of the clean energy source. In an era of rapid global climate change, it is difficult to find a place to start when interconnected problems come into play. But here, the students start with a relevant topic and several questions.

Integrated Science has been making waves for years among Northwood students and parents as a distinctive replacement to the traditional course progression of separated biology, chemistry and physics. So it’s not surprising that a third year of Integrated Science was poorly received by the community when it was introduced last year to meet the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) recommended three-year integrated science model, “Every Science, Every Year.” Given the communal concern and lack of clarity about IS, The Howler researched and compared the educational benefits of both traditional siloed learning and integrated learning. We’ve found integrated learning holds several merits over siloed learning in fostering students who think more critically, hold more comprehensive understandings of content and are better prepared to succeed in various life paths.

Siloed learning, or teaching classes by isolated disciplines, has been used for so long mainly because of its efficiency. Having independent teachers for biology, chemistry and physics has made mapping out the curriculum more straightforward and educational goals more linear. According to STEMscopes, a leading organization creating Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM) curriculum for the US, siloed curriculum follows a logical progression of content comprehension that reaches a foundation of understanding in the subject. In theory, this concrete achievement compels students to feel more accomplished upon finishing the course and teachers to seem more like an expert in a single discipline. Overall, siloed learning is easier to execute for teachers and more comfortable for students.

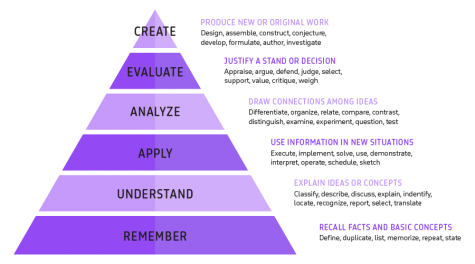

But learning is not meant to be an easy process; we learn the most outside our comfort zone. Oftentimes, tests from the isolated method turn out to be memorization-based rather than comprehension-based, and students rarely retain the information in the long run. Rote memorization does not build understanding, nor is knowing every detail of a topic the ultimate goal of a high school class. On the back-end, while STEM students tend to be overconfident about their career preparedness, only about 55% of employers felt that students possessed required critical thinking and problem-solving skills, according to the 2018 Job Outlook Survey. In this same survey, only 42% of employers felt that students could effectively communicate their ideas. They lack the real-world skills.

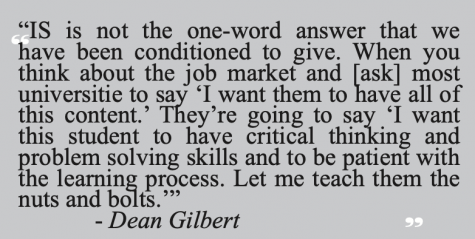

“What [five-scoring AP students struggling in college] were lacking is the ability to synthesize information, to be able to use their critical thinking and problem solving in order to apply what they’ve learned to real world situations,” Next Generation of Science Standards reviewer and STEM consultant Dean Gilbert, who has helped develop California Science Content Standards, said.

Northwood has been teaching integrated STEM classes since its founding in 1999. Instead of teaching students separate topics each year, this method teaches chemistry, biology, physics and earth science, all while increasing the depth of understanding year by year. It aims to challenge students to answer phenomenon-based guiding questions per unit by using what they have learned about various fields through experimentation and modeling.

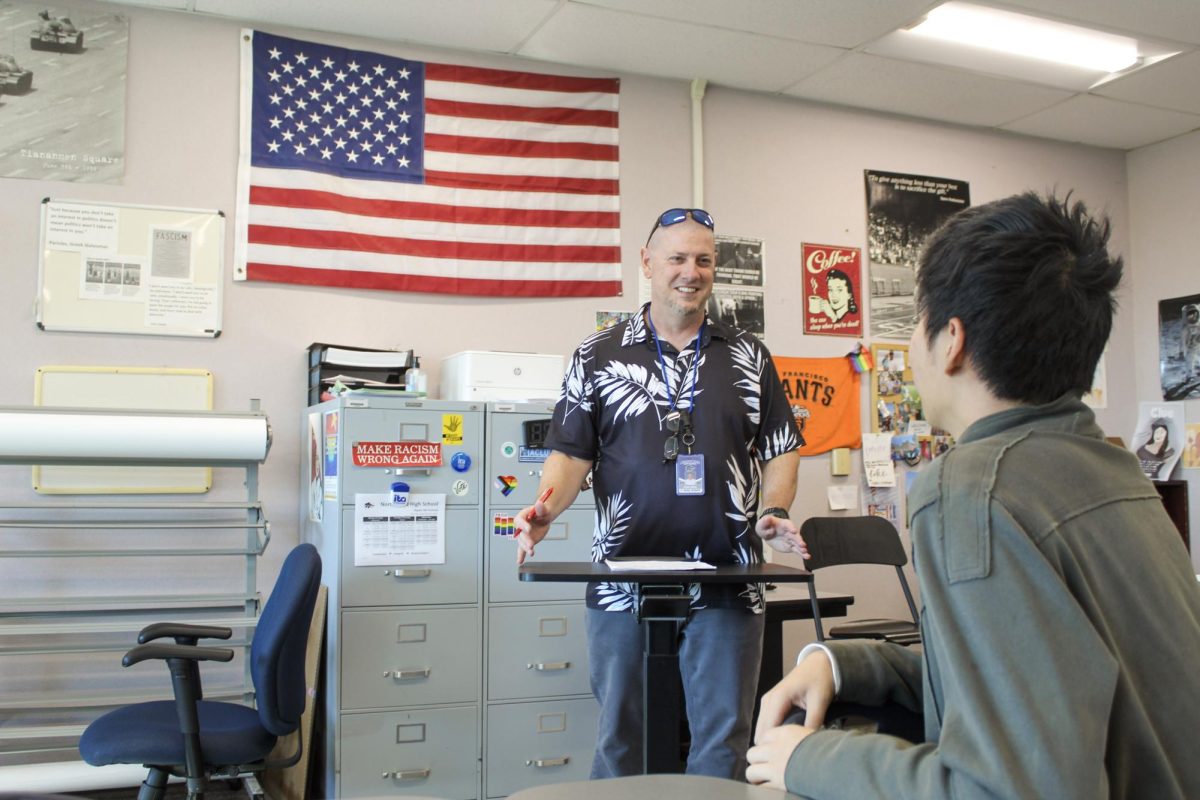

“In terms of whether Integrated Science is good or not, you go to the research. [Both the national and district-wide committees for redesigning the science curriculum to fit the NGSS] read research about how kids learn,” science teacher Mickey Dickson said. “Making connections we know is the best way for us to learn.”

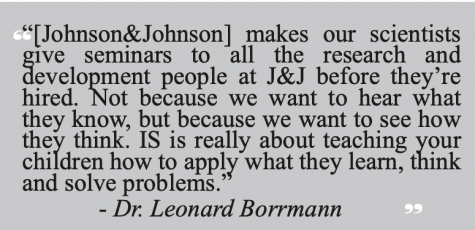

Integrated Science prepares students for real-world careers while providing a better understanding of the content. Our science teachers developed a curriculum where students build on what they have learned from previous disciplines—like using basic chemistry principles to understand the mechanisms of the electron transport chain in biology—to develop a more enduring, holistic understanding of science. They also apply several disciplines to understanding single phenomena or solving single problems. Students get to see the applications of science to aspects of daily life that we might have never explored, like the cellular processes allowing trees to grow, starting with an inquiry-based investigation. The IS pathway teaches NGSS best; in siloed biology, chemistry or physics, it’s nearly impossible to make connections for big, overarching learning objectives. Moreover, this interdisciplinary approach is key to the modern-day workplace that so highly prioritizes collaboration between departments.

A 2019 study on the effects of integrated STEM learning in South Korea from the Korea National University of Education found different degrees of positive effects on student learning. A meta-analysis of several independent studies of different STEM classes found that students were overall rated higher in science engagement, multidisciplinary understanding and eagerness to collaborate. These students faced no detriment to in-depth understanding of each subject. To analyze the long-term effects, this study sampled hundreds of college students comparing those who did and did not take an integrated class (using independent t-tests for those statistics buffs) and found that those who took an integrated class gave statistically significantly higher ratings in real life application, problem solving and interest in science. Interviews of these students corroborated the numbers, as many students felt more engaged in scientific careers and more readily carried the concepts into entrepreneurship. It is worth noting the study mentioned that further research was necessary on the widespread implementation of these programs and teacher training. Furthermore, while this study is not located in the United States, we share the same learning objectives in equipping students for an ever changing, globalized world.

Now that we have looked at the benefits of IS over siloed STEM education, it is important to see why IS faces so much backlash from the Northwood community. In a sample of 328 Northwood students, two-thirds of which were current underclassmen, 50% believed it did not prepare them for life and the median rating for overall experience was a 5 out of 10. There are ultimately three major arguments against Integrated Science these students may be responding to, which we hope to refute in the coming paragraphs. One is that it ruins the college competitiveness of a student.

“We sent our three-year curriculum out to colleges across the nation [lists Ivies, UC system, BU, WashU, etc.] asking them ‘will they accept our integrated program in lieu of the traditional biology, chemistry and physics?’” Gilbert said. “Every single one put their stamp of approval based on the efficacy of the content that we define in our curriculum.”

IS provides the foundation to succeed in APs, and many students in AP Chemistry, Physics or Biology will find that they have already covered and retained much of the content and overarching ideas. Following this “college application” train of thought, that one missing AP science class in junior year is not making or breaking a student’s college application or future career. Widely renowned schools across the country are dropping AP classes entirely, maintaining or even improving their competitiveness in college admissions and careers. If anything, IS cultivates skills needed to succeed and innovate outside class, tackling pressing issues with creative solutions bridging disciplines—something immeasurably meaningful in college and life paths alike.

The second argument is that IS is less rigorous and does not cultivate the intensive, discipline-specific knowledge necessary for today’s scientific solutions. Science teacher David Monge concedes: “If students are saying that IS is watered-down because it has less content, that’s understandable because AP classes cover a lot of content for test-preparation. But AP sciences do not allow you to truly learn. For example, most students tried to rush through the AP Chemistry summer assignment instead of taking it in, so by the time we talk about it two months down the road, they’ve forgotten everything. The pace of an AP class lends itself to providing more content, but it doesn’t lend itself to providing more learning.”

Even then, AP classes are designed to emulate college introductory semester-long courses, now stretched over the span of a year. Strong learning mindsets and study habits are essential to healthily stay on top of the heightened pace down the line. There will be little hand-holding, serving information by the spoonful, and IS brings a taste of practical situations by giving students room to extensively examine, experiment and evaluate.

“IS provides the content that can help teach the important skills. AP content is important for science majors, but not everyone is going to be a PhD or Bachelor of Science in chemistry,” Monge said. “The idea that I’m going to teach you the fundamentals of chemistry that you will remember is a much better mindset.”

Not only does IS have equal levels of rigor (our student sample showed a median rating of 7 out of 10 in difficulty, Dickson’s 19 years worth of IS student surveys showed consistent responses about being challenged by the course and any Integrated Science student struggling to maintain an A will confirm this), but it also better prepares students for the scientific world by focusing on cultivating the applicable “Science and Engineering Practices,” like communication, collaboration and project management. According to Gilbert, “it is estimated the amount of science information doubles every three to four years. If this is the case—if we base scientific literacy on the ‘amount’ of information we learn—a high school student would be obsolete before graduation.” Scientific solutions that require deep dives into specific disciplines are not going to be coming from high school students learning AP Chemistry; they’re going to come from experts who have already acquired professional level problem-solving skills before immersing themselves in their field. Moreover, effective scientists and functioning members of society are defined by their processes in approaching situations and problems, rather than the vast amount of information they possess. We already have supercomputers and other great resources for sharing information.

Another concern worth mentioning is the current lack of teacher education programs preparing instructors to lead these integrated courses. As college systems divide educators into specialty areas, the lack of expertise in every field can be difficult for teachers to answer any possible question posed by the class. That being said, most high school science teachers who obtain a B.S. degree have a broad breadth of knowledge in biology, chemistry and physics, qualifying them to teach at the high school level. The difficulty for finding IS teachers is the willingness to revisit this knowledge from earlier on in their careers and teaching it to students. Yet, the value of admitting one does not have the answer on hand and deciding to research further is severely underrated. Everyone is bound to face the unknown in the future, whether it be in an upper-level academic course or formulating a solution to an unsolved problem to save lives, but the mindset in which one approaches the situation and learns from it is ultimately most valuable.

IS focuses on fostering these critical thinking and problem solving skills to apply to the real world, instead of just information. With yearly professional development training and protected weekly time to collaborate with fellow colleagues, IS teachers can develop the best curriculum to teach us students. IUSD and local groups like the California School Employees Association are especially proactive in supporting teachers for attending conferences and gaining relevant experience at the forefront of academics and education.

However, the key to effective teaching and learning requires a collaboration of everyone involved. With such controversial changes, it is crucial that our school administration is proactively transparent about plans for change and clearly communicate throughout the transitioning process. The administration has improved as of recent in terms of conveying their intent and strategy, and we hope to see patience and understanding grow on both sides. We are all invested in the success of the students—parents, teachers, politicians, administrators—and need to consider every stakeholder, students included, to execute a vision of excellence and equitable education.

Rote memorization and comfort should not define our standard of education. Instead, we should value a better grasp of scientific concepts and a problem-solving mindset that allows students to succeed outside the controlled classroom environment. There is an immense collection of empirical evidence backing the benefits of Integrated Science as a way to teach students important and applicable skills while covering equally in-depth content as siloed learning in the long run. While opposition to Integrated Science has valid intention, the fight is ultimately a stubbornness to change ingrained traditional structures. Yes, we are transitioning to a new system, and it is scary to reform something as important as education. Yes, teachers must pour more effort into training and curriculum development to make it work. But given that education—like all things—must progress and that our dedicated and genuine Northwood teachers are seeking the path less taken (for now) to develop better curriculums for us, the least we can do is be open-minded to the new, especially when it is grounded in evidence. The future will not wait for public education, for the public, to catch up. Integrated Science is built on the core goals and principles of education, preparing our students to be adaptable, global citizens in a diverse, interconnected world.

Fill out this form with your input!

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)