5, 4, 3, 2, 1: reverse procrastination comes to AP registration

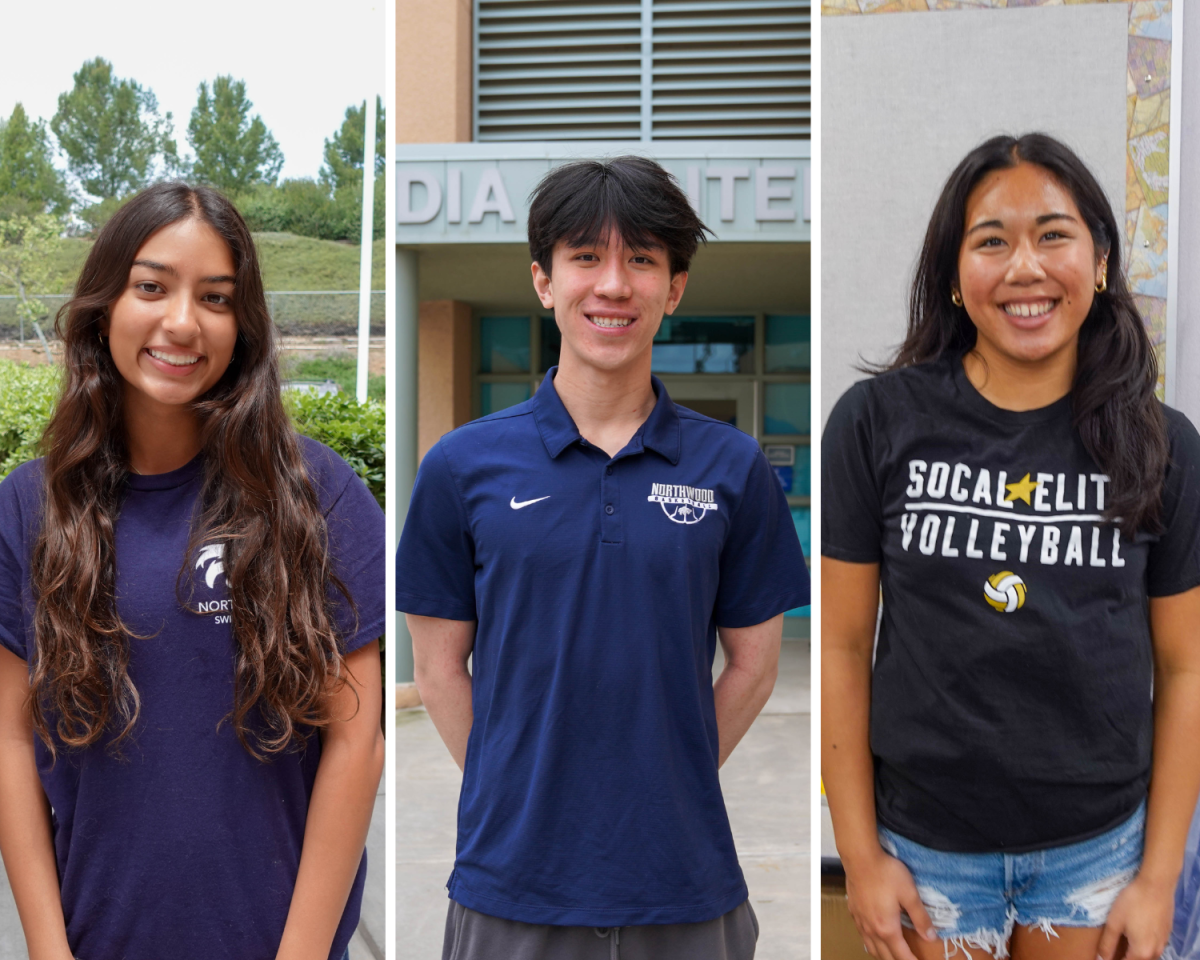

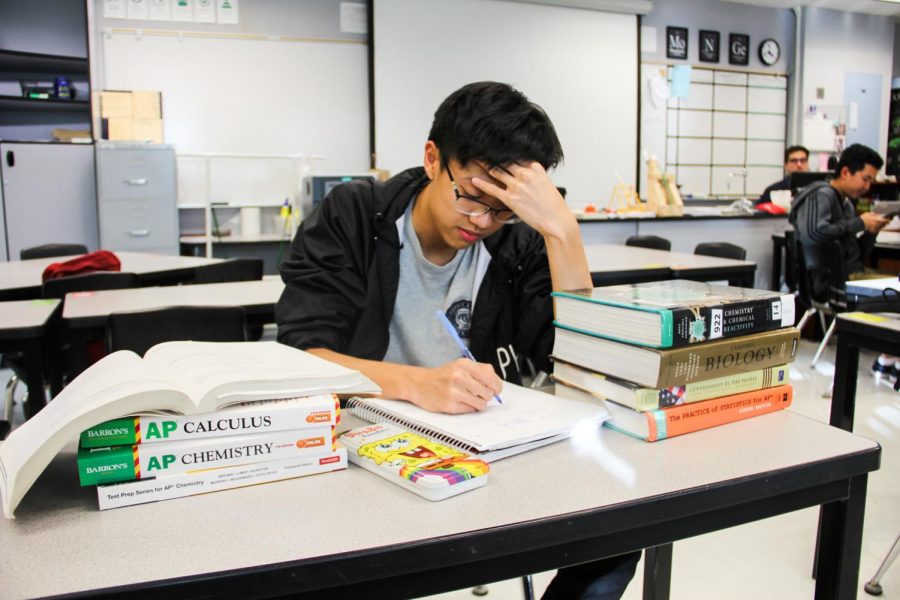

OVERWORKED: Junior Zachary Huang-Ogata struggles under a gargantuan AP courseload.

January 31, 2019

The hardest part of an Irvine student’s life, besides social interaction and maintaining high marks, is the Advanced Placement test season. The student’s full year of rigorous studying, all-nighters and ripped hair culminates in one last exam (or as history teacher Bryan Hoang would call it, a “celebration of knowledge”). However, recent decisions by the test-giving administration may make it increasingly difficult for students to take the exams. The College Board is implementing changes to their registration policy by requiring students to sign up for tests in the fall. Starting in the 2019 school year, students must register for AP examinations as school begins and will be charged additional fees for late registration and cancellation. These changes are an unreasonable and unfounded solution to the issues the College Board cites for advocating this plan.

One of the largest issues with the new policy is the monetary penalties that students incur. On top of an already large price for taking a test itself ($94 according to the College Board), students will be charged $40 for either late registration or cancellation.

This especially harms financially disadvantaged students who already pay a hefty sum for AP tests. Regardless of whether discounts are applied to students from underrepresented backgrounds, the very concept of extended fees hurts their financial status. If a student realizes that a course is too difficult or does not wish to receive a score from the official exam, they must pay more money for an obligation made months before. Because many AP courses are rigorous and model college courses, this is a common decision that students make and will continue to make.

Although there were already fees applied upon cancellation, allowing students to register later gave them the leeway to decide later on whether or not they wish to take a test, not to mention the fact that they may apply for a refund under the current system. Changing this system by adding more fees, in turn, disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds and forces them to make an expensive obligation before delving into their courses.

The College Board really cites only a single justification for its change of policy: that there will be a “boost” in the “learning culture in AP classrooms” in addition to having students “more engaged” when signing up for tests early. There are a few issues with these statements and the study the College Board analyzes for evidence.

First, promoting the “in it to win it” mindset to students to encourage them to take the test only entrenches the idea that students take AP courses solely for scores and status. By writing that their data indicates a higher number of students completing courses and taking the exams under early registration, the College Board effectively reinforces the idea that the more students taking the test, the better. Obviously, we cannot deduce that the organization is simply trying to force more tests to be taken, but it certainly fails to acknowledge that students take courses for their interest in them. If one truly is invested in a subject and wishes to study it in an advanced course, then it’s reason- able to assume they would take both the class and the test. However, as the College Board claims that “ask- ing students to commit to taking the exam at the start of the course results in three additional exams taken,” it can reasonably be argued that these new policies neglect the notion that students take tests for their own interests and instead serve the organization’s desire to open more test spots and demand students to substitute quantity for quality.

Second, it is far too subjective of a claim to argue that students would be “more invested” in their classes be- cause of early registration. As mentioned earlier, students simply will not have the time to consider whether taking the course is worth it. If a student decides to take AP Biology be- cause of their slight interest in becoming a doctor but decides three months later that the course is too difficult, they must pay their way out of taking the exam or risk getting a low score in a subject they no longer care for. The College Board responds to this by arguing that an equal number of students in the current policy and new system take the test, but they fail to account for a logical consequence of this method; their sampling data was taken over the course of a single year, which indicates an inability to foresee the consequences. Furthermore, the College Board proclaims that there will be nearly “1.5 times the growth in students taking exams” and “nearly double the growth in the number of low-income students taking exams.” Although we cannot speak for certain, this evidence only indicates that the students binded to taking the test were reasonably unable to pay for late registration or cancellation, and were thus forced to take the test.

A third claim concerns seniors who take AP courses and tests for credit. College decisions come out be- tween December and March, meaning seniors who take these courses must gamble on the possibility that their decided college accepts the score as credit for a course. The only alternative for undecided students (which make up a large portion of the senior population) would be to pay late fees or cancel a test on a course they wish to have completed in their final high school year, which, again, forces students to fork over more money on a decision made months before. Such a restrictive strategy to funnel money from unknowing students is one all AP students should be aware of, and one that the College Board should not implement out of basic integrity.

The ultimate impact of the new policy goes beyond minor inconveniences to some students. In general, the College Board ought to create systems that it knows will help as many students as possible, test these systems beyond only a single year and attempt to reason with the opinions of the students from a lesser emphasis on quantity over quality.

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-1200x800.jpg)

![AAAAAND ANOTHER THING: [CENSORED] [REDACTED] [BABY SCREAMING] [SIRENS] [SILENCE].](https://thehowleronline.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/lucy-300x200.jpg)