It’s hard to feel like you’re failing. Trust me, we know. We all do.

You wanted that position. How did he get it over me? He doesn’t deserve it. You wanted that 97 on your essay. But she got it? Mine was clearly better. It must be biased.

You’ve been collecting extracurriculars like Pokémon cards. You’ve got your founder. Your president. You have your transcript lined with hard-earned As. But somehow, somehow… none of this puts you on par with the shining star in your class who’s bound to get accepted by an Ivy League, recruited by a D1 school. None of this is enough to get your parents to stop yelling at you about doing more… shining brighter than everyone else, climbing your way, knocking the others down under your footsteps, clambering towards the final trophy. Northwood has long faced a competitive culture, but never before has the me-before-others mentality been so prominent in the everyday experience. Never before has the competition been so gruesome and slanderous toward others, and yet at the same time so performative and lacking substance for the individual. It’s harming our school culture and the enjoyment of our activities on campus.

There are three categories of toxic competitiveness we have observed at Northwood: the diminishing of others’ accomplishments to feel better about your own shortcomings, half-hearted participation in extracurricular activities for the purpose of padding the college resume and humble bragging about trivial matters such as lack of sleep.

We all lose with “me first” mentalities

Self-centrism is often thought of as a quickly identifiable trait—someone who is full of themselves and who draws attention towards themselves. But here at Northwood, it manifests subtly, and people must learn to recognize when they may be impacted by this mentality subconsciously.

One manifestation of this mentality is an unwillingness to support others. Helping others is seen as giving them an advantage, an impossible choice not to be risked. It’ll make them better than me. Individual goals trump cooperation and empathy, so people are turning the other way, saying “Sorry, I don’t know. Can’t help you.”

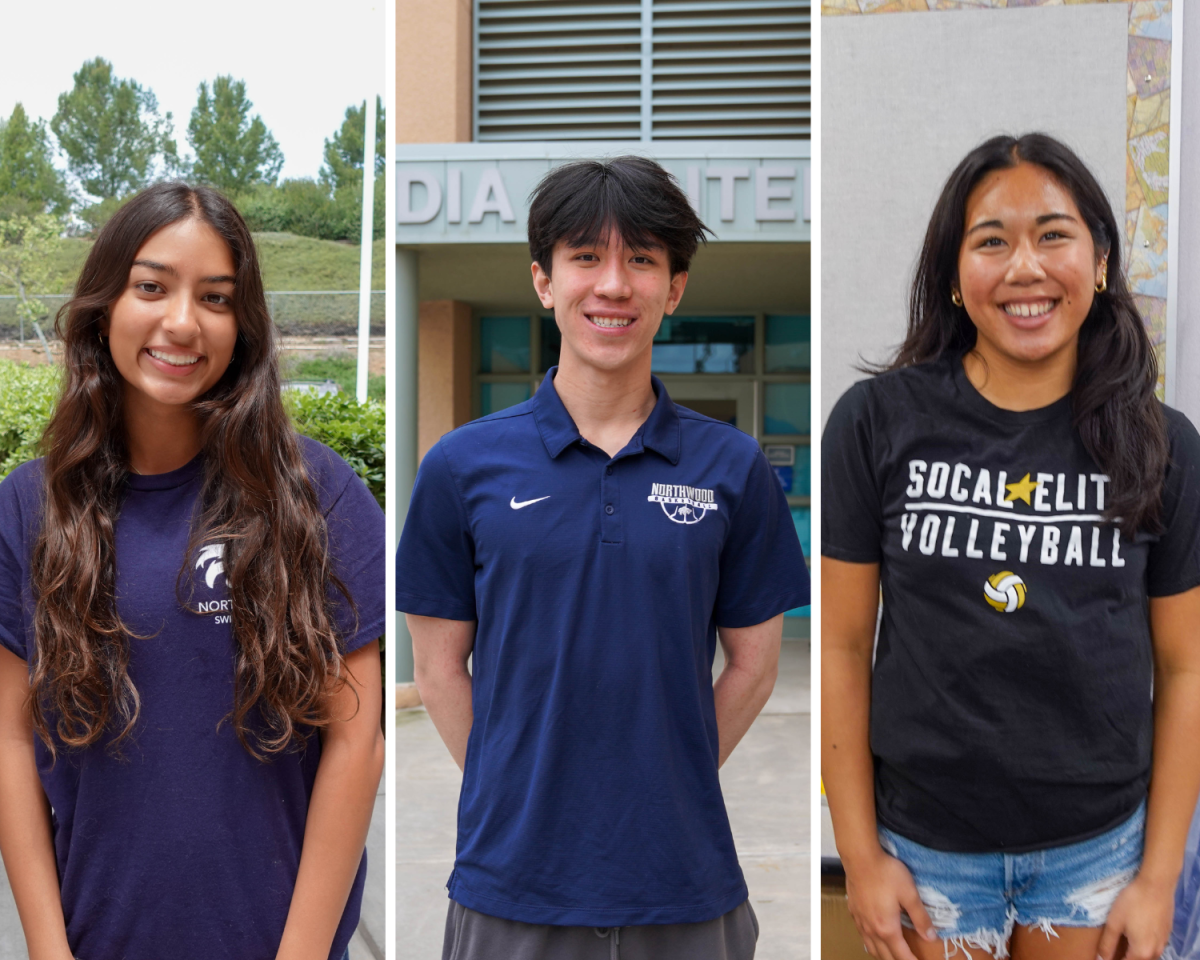

“Especially in a sport like track and field, which is considered a team sport, there are individual goals that we want to achieve,” senior Sara Kabbara said. “And this sometimes gets in the way of team goals and overall camaraderie.”

We are also observing students who—sometimes intentionally, sometimes unknowingly—increasingly fail to respect other people’s accomplishments. When they are knocked down for getting a bad grade or not getting the result they expected, they talk badly about others who made it. This only creates a culture of negativity and hatred on campus, wrongfully attributed to others when people should be looking inwardly at themselves.

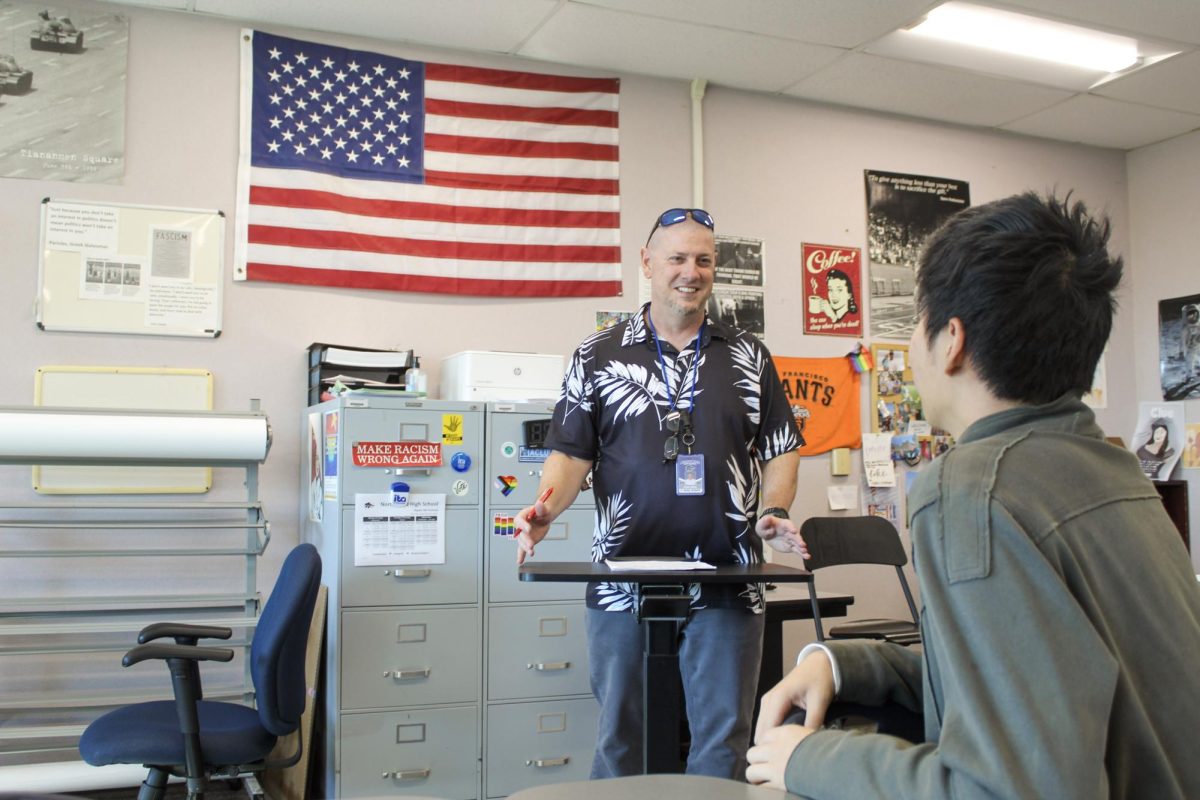

“It doesn’t matter how someone else does on a test. The whole grading system that we’ve tried to create at Northwood is about individual journeys and pathways,” AP World History teacher Logan Sewell said. “Sometimes it feels like we as teachers are fighting an uphill battle with the inherent competition between students.”

In order to foster a more cooperative, togetherness-minded environment, students must be slow to seek attention, practice the humility they preach and know when to put their self-interest aside for the betterment of everyone as a collective. When things do not go your way, limit your negative language. Phrases like “He didn’t deserve it,” “I deserved it more” and “This is biased” need to be eliminated from our vocabulary on campus.

Chasing the elusive Ivy League can cost you

Simply winning is everything. Being the best on paper is everything. That has been the culture on campus recently. And this ruthless endeavor to win at any cost is coming at the expense of joy and enjoyment. We have been observing many students on campus who seem to be joining extracurricular activities and reaching for leadership titles solely for their inherent “college application value.”

Merely making it—getting a leadership title in a club, being selected into Science Olympiad, The Howler, a varsity team—is starting to become like a checkmark to get closer to a dream college. Not only does this involvement become performative and surface level for the individual, it also lowers the morale for the other people who are actually passionate about the organization.

“Throughout the marching band season, we saw very strong leaders emerge, but we also saw leaders that demonstrated no leadership apart from the one projected from their title,” drum major senior Laura Estrada said. “In my opinion, one of the most important traits of a leader is passion. Without being passionate, being a leader will feel like a chore rather than an opportunity.”

While it’s good to be dedicated and build a hard working mentality, it’s not just a “hard working” or “hardly working” world. We must retrain our thinking: not getting first place is okay. You aren’t lesser because of it. Participate in extracurriculars for enjoyment, not a line on a resume. The desire to want to seem “achieved” by taking on too many burdens is baseless.

“While involvement in extracurriculars is indeed crucial to the application process, it’s essential to prioritize quality over quantity,” admissions consultant Christopher Rim wrote on Forbes. “Admissions officers are more interested in your authentic commitment and demonstrated leadership within a select few activities than in superficial involvement in numerous clubs.”

What is best for you is to prioritize yourself and your interests. Instead of doing everything to please one school, the mindset must be shifted to simply doing what you love. The place that you end up in will be the best place for you to grow and develop.

Humblebrags breed toxic expectations

Words are important, and should be used wisely and productively. Right now, Northwood culture seems to be rooted in using these words to brag about productivity more than anything else.

In 2010, “humblebrag” was coined as an official term in the Merriam-Webster dictionary. Essentially, it is to make a seemingly modest, self-critical or casual statement that is really meant to draw attention to an admirable or impressive quality.

“I only got six hours of sleep last night.”

“Wow, you got six? You’re so lucky! I only got two.”

“What did you get on your test?”

“Oh, not too good. Just a 92. I bet you did better.”

You’ve probably heard such conversations around campus. Maybe you have accidentally partaken too. But this is exactly the problem: mundane conversations, probably one that you’ve had first period before receiving this newspaper, are creating a debilitating environment.

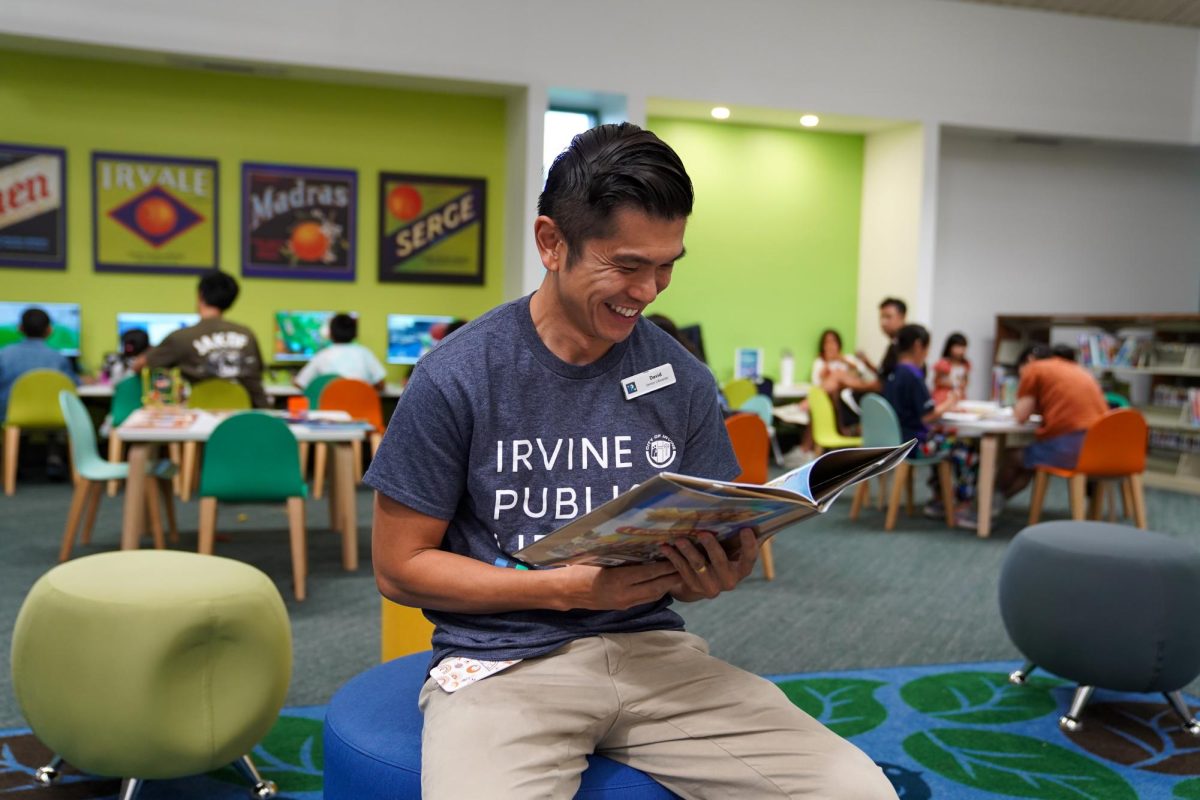

“Sometimes students will wonder if they are worthy or if they have value if they aren’t getting better grades than everyone else,” Calculus teacher David Lee said. “You’re gonna do awesome things no matter what grade you got or what clubs you are a part of.”

When you only get a 92 on your AP Biology test and complain about how you did so bad and now your grade is going to drop and now you won’t get into any Ivies and—

These “humblebrags” perpetuate a standard of toxic expectations in which you can only succeed if you’re suffering worse than everyone else. Words are precious: so why should we be using them so unnecessarily? Practice real humility, not this fake attention-seeking behavior.

To the parents: Some of it is coming from you

Sometimes, competition can yield a positive force. It motivates you to do your best, to give your best effort and reach your full potential. In fact, a study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that the social motivation of competition encourages students to exert greater effort than they might independently feel driven to apply. However, focusing solely on academic success can come at the detriment of what really matters.

“The competitiveness at Northwood is grade-based,” sophomore Emma Walton said. “I’ve seen people put down out-of-school commitments such as sports and mental health care at the expense of a letter on a report card.”

Competition can be a good thing, but it is excessive when it leads to aggression, anxiety and frustration.

We’ve addressed this with students. Of course, students need to take better steps to fix this culture, but it’s not just their fault. Some of this culture can be traced to the over-involvement of parents. While research shows that parental involvement can be key to academic success, according to the National PTA, over-involvement can have an opposite effect.

One study published in the American Psychological Association found that students of over-involved parents had higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of self-efficacy, leading to poorer college adjustment.

Parents need to stop dictating that their child must join a specific activity, must win a specific title or must be perfect in everything they do.

Northwood is not a competition of who gets the least amount of sleep. Northwood is not a competition of who has the least amount of rest between their extracurricular activities. Northwood is not a place of crushing others just to ensure you succeed.

Northwood is a place where we support each other to make sure that all of us can achieve our dreams, whatever those may be.

Shut down the bragging, shut down the “Ivy League or nothing” mindset. Stop dragging people down so that only you can lift the shiny trophy above your head. Instead, let’s raise each other up on that pedestal—there’s room for us all.