We are not defined by our bloodlines

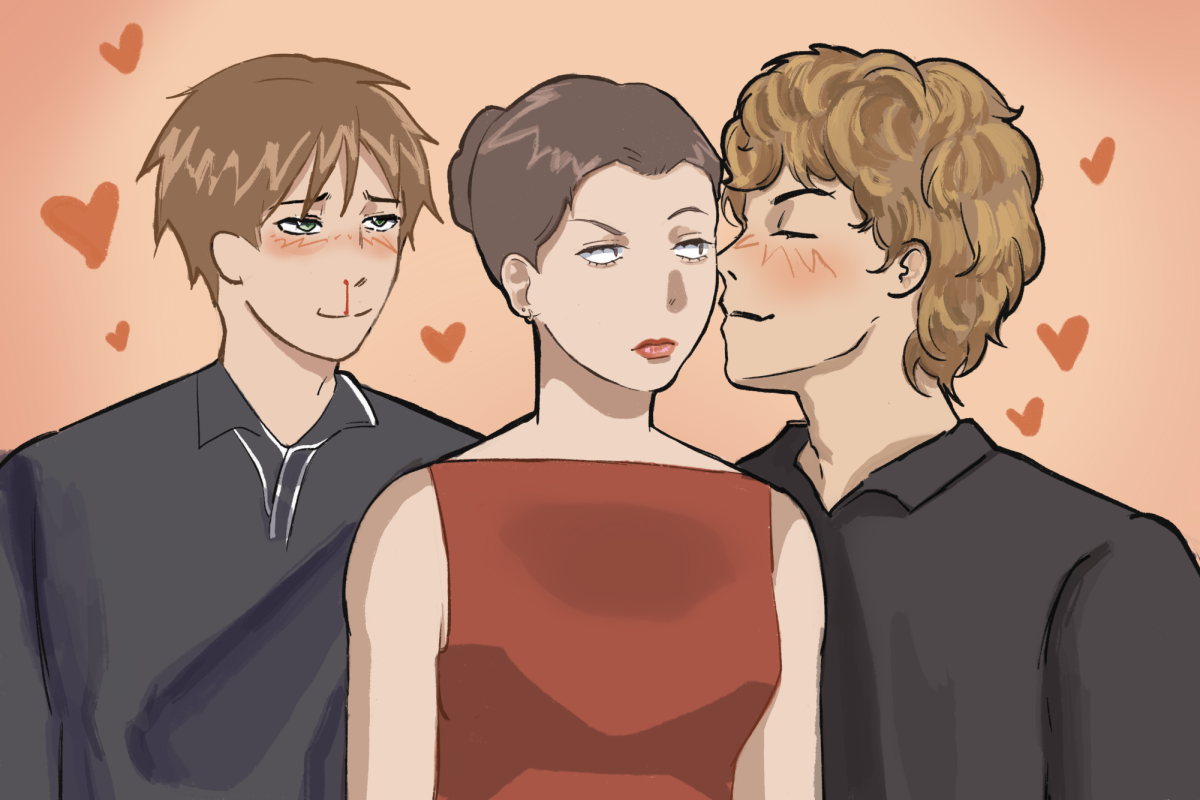

LOOMING SHADOWS: Being constantly compared to the overwhelming academic achievement of your sibling can feel like living in their shadow.

April 12, 2023

You share 50% of DNA with your siblings. You share a house, maybe clothes, maybe looks, a last name. But there is an important distinction you should not share: a reputation. An identity. But if that is the case, why are countless students in the classroom still being defined by the siblings that came before them?

Everyone has heard the comments made in class before. The teacher goes down the roster calling names and stops at one.

“Are you related to…?”

From there, from just the initial reading of the family name, an inevitable, innate bias is placed upon the individual. This bias can be a positive one—their sibling may have been an academically-successful student whose glorious reputation now passes onto the shoulders of the younger. It can also be a negative one—their sibling, maybe even their parents, stirred up trouble and now the younger sibling bears that judgment.

Either way, these biases are problematic and harmful. And while bias is an unavoidable part of the human experience, we must make conscious strides to judge people not by their last name, but by their unique characteristics and strengths as an individual separate from the family unit.

An immense amount of pressure is placed on an individual once initial assumptions are made about them on the basis of their sibling’s performance or behavior. The sibling of someone who used to constantly “act up” might feel as though they must overcorrect their behavior to not be seen in alignment with the conduct of their sibling; the sibling of someone who constantly achieved the highest grades and honors may feel as though they must “live up” to that success.

These assumptions and expectations, of course, go unsaid by teachers in the classroom. An article from Medium, however, points out how “even though most expectations go unsaid, we still know and are often keenly aware of the expectations others have for us.” Humans are social creatures that can pick up on cues from others, and sometimes, even the mere “are you related to…?” questions can spark the worry that expectations are being placed on them.

Over time, these expectations can lead to poor mental health, including depression, anxiety, lowered self-esteem and higher stress levels according to BMC Psychiatry.

A 2015 study by BYU professor Alex Jensen investigated this phenomenon in academia by looking into the academic achievements of 388 teen first- and second-born siblings in 17 school districts across the United States. Research found that preconceived expectations correlated to worse academic performance.

The beliefs held by teachers and parents that one sibling was “smarter” or “better” than the other led individuals to feel as though they were less capable, which contributed to poorer academic performance. This translated to a 0.21 difference in GPA among participants. While it may seem like a small difference, it is crucial to understand that this trend was consistent.

Meaning, there is clearly a problem present.

Some people might misunderstand this problem. Parents and teachers alike may claim “No, we don’t have these expectations. We don’t feel that. We’re unbiased.” And perhaps there is truth in that—no one is consciously trying to compare two individuals together, and when it happens subconsciously, the logical part of the brain must be trying to mitigate such unfair feelings.

The problem really is that students think that these expectations are placed on them stemming from comments about their siblings. Students know that a teacher would not blatantly draw comparisons out of malintentions. However, they still understand that a teacher may think about them in certain ways internally, and thus the pressures they feel come from within: a need to prove to themselves that they are just as worthy as their sibling, masked as a need to prove it to other people.

The classrooms must start to account for the problematic nature of associating siblings together. Limiting even the small, “trivial” comments—the “are you related to…”s, the “your sibling did this…”—can help lessen the pressure that students feel. In a classroom, individuals should be free to truly feel like individuals, free from comparison.

We are not defined by our bloodlines—not defined by the good, the bad and everything in between that make up our family names. The focus should be not on the last name, but on the first name: of the individual themselves.