Diversity in the Oscars

THE GOLDEN IDEAL: The Oscars statuette is a symbol that celebrates the capabilities of people belonging to all ethnic backgrounds and gender identities.

March 28, 2023

As the 95th Oscars came to a close on March 12, the stand-out of the night was undoubtedly “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” which ended the ceremony with a total of seven award wins out of the 11 total nominations it received this year, including the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Praised for its remarkable showcase of diversity in both cast and crew, “Everything Everywhere All At Once’s” win was accompanied by a series of other groundbreaking accomplishments. This included Michelle Yeoh’s historic win as the first Asian American to receive the Oscar for Best Actress and only the second woman of color to do so, as well as Ke Huy Quan becoming the second Asian American man to win Best Supporting Actor.

Despite the undeniable progress the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science has made in terms of diversity, the fact remains that the rarity of these events in the 21st century is a reflection of not just the Oscars’ long-standing underrepresentation of marginalized groups, but the continual need for progress towards equity in the film industry itself.

The Oscars, among many other of the world’s most prestigious film awards, have been historically white and male dominated. Research from the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, which investigates the gender, race and ethnicity of Academy Award nominees and winners, reveals that since 1929 the ratio of male to female nominees across the Oscars has remained at around 5 to 1, while only 16% of Oscar winners in the past 95 years have been women. Women of color make up less than 2% of all Oscar nominees. Likewise, data regarding race and ethnicity of nominees highlights more disparities. Throughout history, people from marginalized groups comprise only 6% of both Oscar nominees and of Oscar award winners.

These trends are problematic for a variety of reasons, one being that underrecognition of their contributions simply discredits their efforts and can often prove discouraging to those entering the film industry. In addition, when nominees and winners fail to reflect the demographics of our society, there exists the danger of inaccurate portrayals of diverse cultures and lack of acknowledgment surrounding the vibrant stories that these marginalized communities have to share. The power of film lies in its ability to touch the hearts of viewers, something that is difficult to achieve without the sense of belonging that can be created by a diverse cast and crew.

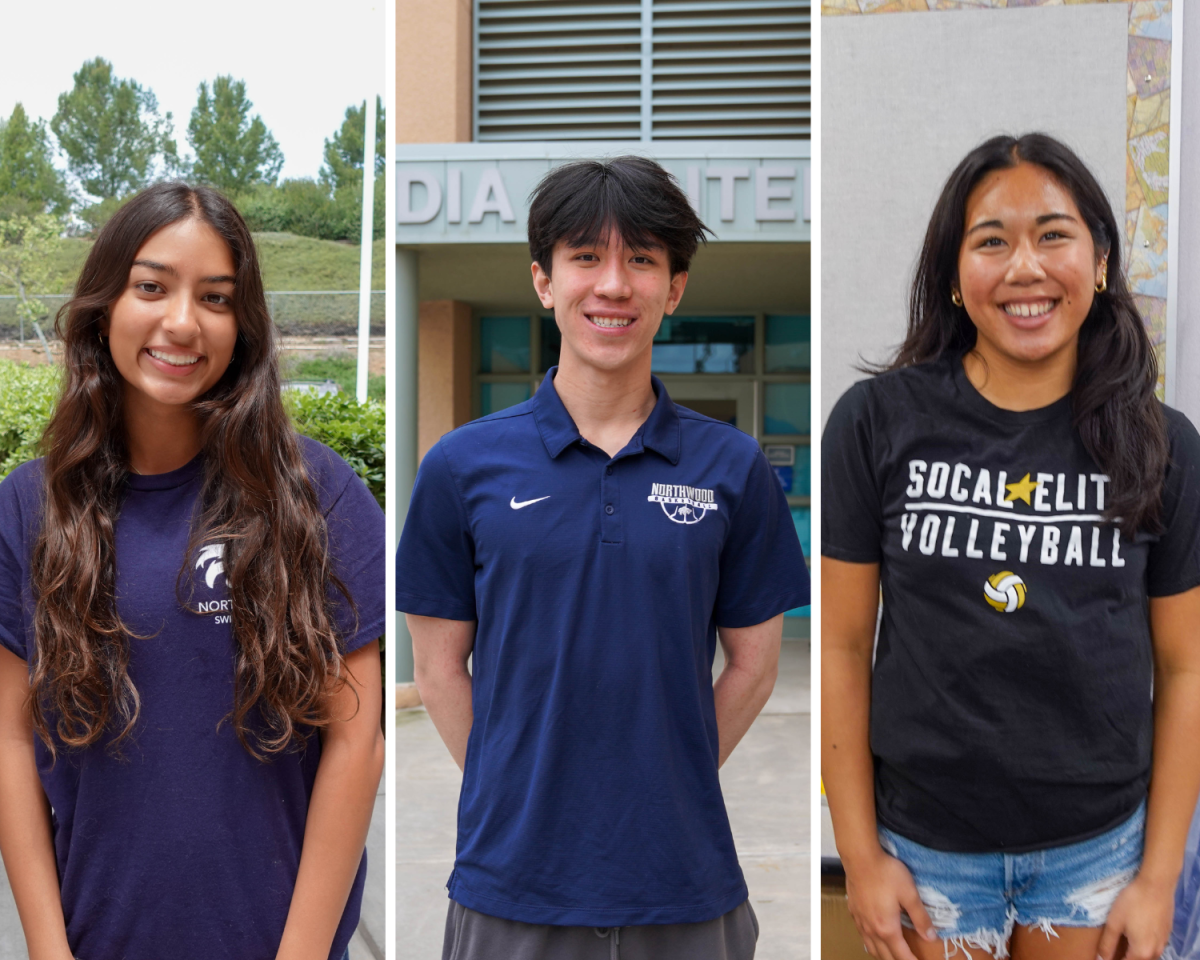

“As a member of NTV and a woman of color, this Oscars event really resonated with me because it gave me the hope that I can make it in the industry,” NTV ASB Producer and senior Kriti Jain said. “Films that would’ve seemed weird 10 years ago and probably wouldn’t have even been greenlit to be filmed are now being given seven awards.”

Although the Academy has made strides to ensure equal representation, announcing that film submissions to the Best Picture category will be required to fulfill at least two out of four inclusion thresholds starting from next year’s Oscars and adding new members to its voting committee to adjust the historically male-dominated voting body, such actions by themselves are unable to create significant change unless accompanied by a willingness to pursue diversity in the film industry itself.

For instance, even in a year of historical breakthroughs for the Oscars, not a single female director was nominated for Best Director. This comes as no big surprise, considering that female directors made up only 18% of directors as of 2022, according to research from San Diego State University.

This example is perhaps the most indicative of the underlying reason why the Oscars are not and cannot be fully representative of filmgoer populations. The problem lies not simply within voting boards and the confines of the nomination process, but rather alludes to a broader issue—It is impossible to expect marginalized groups to be accurately and proportionately represented in film awards when they are not in the industry itself.

Such standards like those introduced by the Academy can act as practical safeguards only when the barriers preventing marginalized groups from entering the industry are first torn down. A study conducted by McKinsey and Company found that not only do Black actors receive less opportunities in the industry to secure roles as compared to their white counterparts, the Black community faces challenges like lack of representation in off-screen roles as well.

According to the McKinsey study, “Films of any kind with two or more Black professionals in off-screen creative roles (producer, writer or director, for example) receive significantly lower production budgets—more than 40 percent less than other films. The disparities are particularly notable given that these films make 10 percent more in box-office revenues per dollar invested in prints and advertising, compared with films with no or just one Black creative professional.”

Losing out tens of billions each year by underrepresenting the Black community alone, beyond the harm that a lack of diversity and inclusion can create for modern audiences, the film industry itself is also suffering. It is clear that audiences are eager to see themselves reflected in films, and if the harm in underrepresentation wasn’t already an obvious indication of the industry’s failures, the numbers also speak volumes.

This year’s Oscars have given hope to audiences around the globe, paving the way for greater changes in inclusivity to follow. Now, the film industry itself must renew its commitment to lift up marginalized voices, breaking down institutional barriers so that we may witness more moments like these at Oscars to come.