Student anonymity in grading

HANDWRITING JUST AIN’T RIGHT: When there’s more efficient and fair methods of evaluating students, educators should consider turning away from handwritten work.

January 6, 2023

The struggle of a weary hand scrawling barely decipherable words against a ticking clock is a familiar tale to all students. For most, it may feel like a step back to the stone age, before computers, where the only option was for students to be assessed by putting pencil to paper. Handwriting assessments are inherently flawed because they lead graders to judge on the quality of the handwriting and not the validity of ideas. In a larger context, adherence to compulsory handwriting assessments follows the lack of progress made towards blind grading.

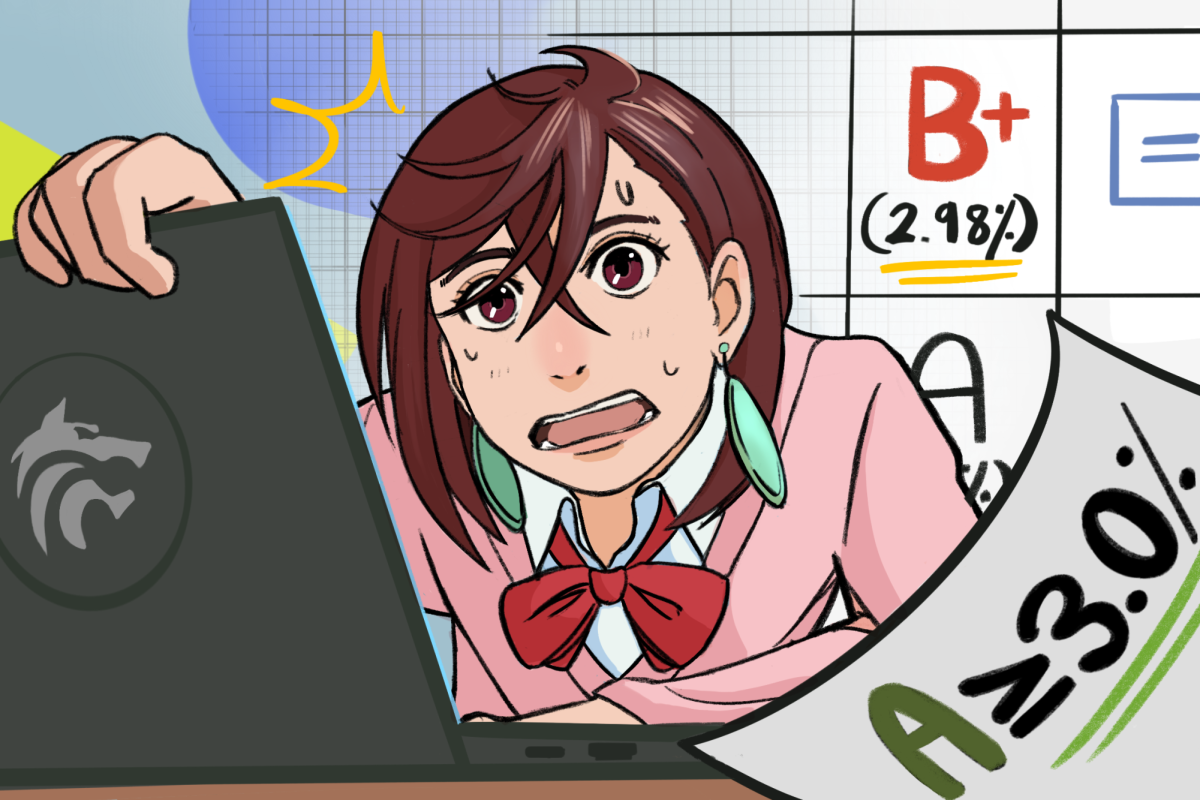

The positives of typed assignments reflect the benefits from blind grading: ensuring standardization and anonymity across students. A resource from the Yale Poorvu Center of Teaching and Learning cites a 2013 study, “The Risk of a Halo Bias as a Reason to Keep Students Anonymous During Grading,” and encourages typed assignments over identifiable handwriting. These implicit biases include the Halo Bias which is when students that are perceived as better based on past work or behavior are rewarded with higher grades for the same work as another student.

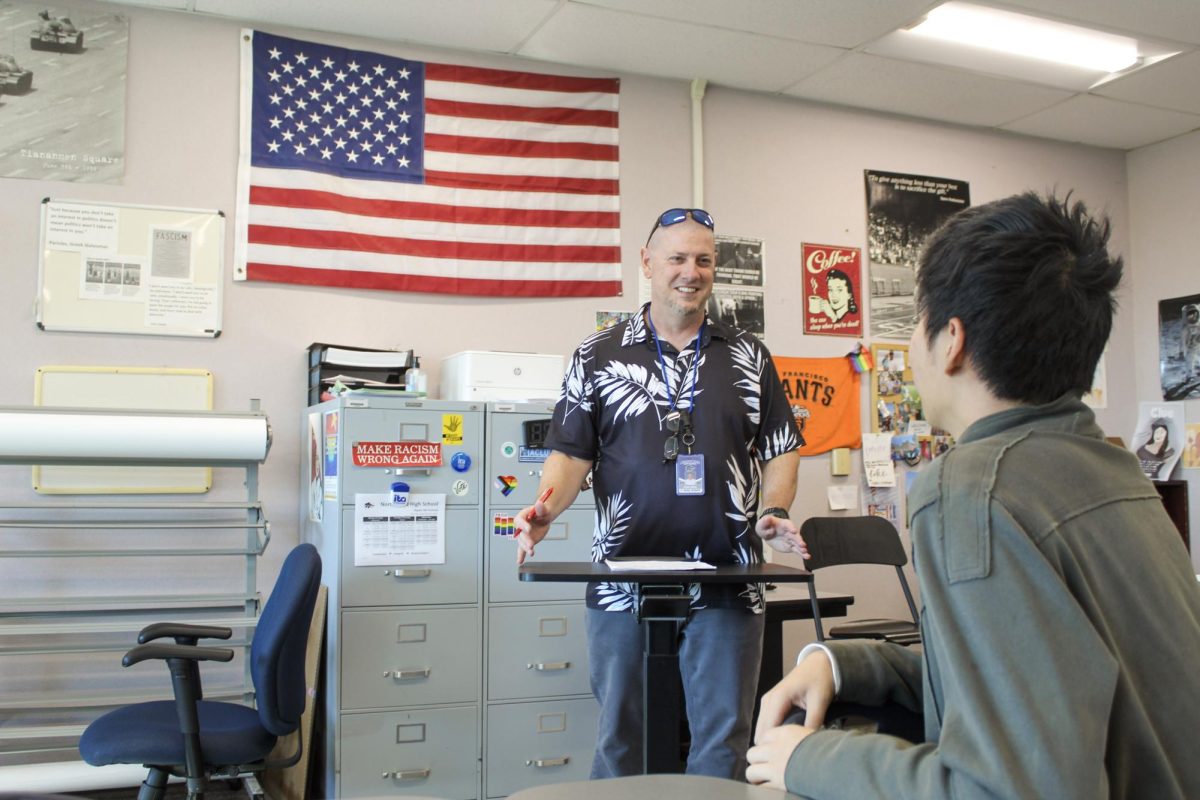

The most efficient way to reduce Halo Bias is switching to blind grading. The policy of blind grading decreases implicit biases of the grader through methods that create uniform assignments across students, such as using ID numbers instead of names and using typed rather than handwritten responses. At Northwood, this method of anonymizing assignments is used in AP Government, AP Biology and AP Environmental Science where ID numbers are used on FRQs.

“I might unknowingly grade easier on students who are known to perform proficiently because I’ll assume they do know the content, and then more harsh for students who don’t usually perform well,” AP Government teacher Zane Pang said. “Anonymized responses keep grading more accurate and less prone to bias.”

Still, handwriting may reveal the identity of students which leads graders to judge on the quality of handwriting rather than the content, and to be inadvertently biased since handwriting is easily tied to preconceptions.

The implicit bias against students with poor handwriting is well-documented. A study published in American Educational Research Journal, analyzed the results of 420 teachers grading essays of different levels of handwriting neatness when the content was exactly the same. Even when graders were reminded to only grade based on content, there was a statistically significant difference between neater and messier samples.

Another study published in Bar Ilan University found legible pen-written essays scored nearly 17% higher than messier essays of the same quality. This disparity demonstrates a significant impact to a student’s grade based simply on the quality of their handwriting, but the implications of this are more sinister than a simple difference in grade.

Given that there is bias created through traditional grading, teachers who assign handwritten samples are also unconsciously supporting structural racial, gender, class and native language privilege among students. An experiment conducted by the American Economic Journal randomized the details of students in India printed on exam sheets and discovered that low castes were graded lower than high castes. These findings correlate to implicit discrimination of students based on socioeconomic status.

These biases begin affecting students as early as elementary school. In an experimental study, David Quinn, a researcher at University of Southern California assigned 1500 teachers two writing samples that were identical other than the either stereotypically white or black names. For the teachers who got the Connor version, 35 percent marked it as second-grade level work or better, but only about 30 percent for the Dashawn version. Not only was there a grade disparity observed from the perceived race of the student, but white teachers were also 8 percentage points less likely to rate the Dashawn sample as being on grade level than the Connor sample while POC teachers graded them the same. Leaving identifiable characteristics, such as names, gives way to implicit biases just as handwriting does, supporting the necessity of blind grading.

The subjectivity of handwriting is detrimental to standards based grading methods that value content over behavior or expression. Since there is no way to ensure all students have the same quality of handwriting and longhand lessons in elementary school are few and far between, the clear solution is to allow students to type written assignments.

There are valid concerns regarding computerized testing, but all can be easily overcome with technological resources, many of which are readily available in IUSD. Turnitin.com can check for plagiarism, circumventing anyone from copy-pasting into their essay. Students can be prevented from navigating to other sites through Blocksi which allows for teachers to simultaneously view the chromebook screens of students enrolled in their class. Privacy concerns can be mitigated with Blocksi which can be enabled to only work during school hours.

California’s standardized state exams have been digital since their start in 2013, and College Board will transition the SATs to a digital format in 2023. With such an established precedent for the security and reliability of digital exams, it’s clear that the risks do not outweigh the benefits.

Let’s be real- an employer will never ask for pages of handwritten documents over neatly typed ones, and teachers certainly prefer 12pt Times New Roman over handwritten chicken scratch.

Another point of concern against blind grading is equity for English learners and others who might struggle with grammar and word choice in an essay. When teachers know the background of their students, they can contextualize the responses better. This is easily overcome through clear rubrics with learning targets that eliminate grammar and expression errors from the final grade, particularly in non-English secondary classrooms such as math and science. Students should not need to demonstrate mastery of English conventions to complete a government FRQ or a science lab report. Additionally, typing those assignments could allow students access to spell checkers and grammar tools that might help them spot errors before an assignment is submitted.

As handwriting standards such as cursive writing are no longer explicitly taught, and emphasis has instead shifted to being computer literate, there’s little reason to continue handwriting for the sake of tradition. Let’s be real- an employer will never ask for pages of handwritten documents over neatly typed ones, and teachers certainly prefer 12pt Times New Roman over handwritten chicken scratch. It’s time to fully embrace the advantages we gain from widespread use of technology to eliminate any obstacles standing in the way of fair education.