Where do we draw the line when it comes to true crime?

RATINGS OVER REALITY: The recent influx in true crime dramatizations should remind viewers to consume this genre ethically and not as pure entertainment.

October 29, 2022

As the Halloween season is upon us, you may find yourself gravitating towards a classic horror movie or even an episode of Buzzfeed Unsolved. Real life acts of violence have long been exploited in the media through tabloids and highly-publicized trials, but more recently, true crime dramatizations are the subject of much controversy. With the recent releases of Netflix’s “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” and “The Jeffrey Dahmer Tapes,” the question begs to be answered: Where do we draw the line when it comes to society’s consumption of true crime?

Though society has long profited off the dramatization of tragedy, this genre has only recently gained intense prestige. With the digestible format of 60-second TikToks and Instagram reels, word of the new documentaries have spread like wildfire. Taking a closer look into real life tragedy has some benefits, as it can renew interest in cold cases and explore the injustices of judicial systems. However, the true crime genre is often marred by its tendency to evoke insensitivity and prioritize ratings over ethicality.

“Monster” is based on the capture of American serial killer and cannibal Jeffrey Dahmer who murdered 17 men from the late 70s to early 90s while residing in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The series goes into great detail of the processes Dahmer utilized to lure his victims and has become one of Netflix’s greatest hits with over 496 million watch hours in two weeks.

With rising acclaim for its star actor Evan Peters’ portrayal of Dahmer, this public reaction has manifested itself into a mistaken idolization of Dahmer that has grown significantly among internet sleuths. Many have channeled their fascinations by using Dahmer cosplays as Halloween costumes, which Shirley Hughes, mother of victim Tony Hughes, has condemned as exploitative and traumatizing.

This sexualization of serial killers is yet another alarming byproduct of the increase in true crime dramatizations, also seen with the reactions to Zac Efron’s casting as Ted Bundy in Netflix’s 2019 “Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes.”

Aside from this, victims and their families have virtually no way to opt out of media coverage, as court footage is often within the public domain.

This sentiment was echoed by Rita Isbell, sister of Errol Lindsey, whose victim impact statement during the Dahmer trial was recreated verbatim without her consent in “Monster.” Though Peters himself has stated in promotional videos that “it felt important to be respectful to the victims, to the victims’ families,” those impacted have repeatedly emphasized the triggering nature of recreations in reopening already deep wounds.

“It’s sad that they’re just making money off of this tragedy. That’s just greed,” Isbell said in an essay on The Insider. “I didn’t watch the whole show. I don’t need to watch it. I lived it. I know exactly what happened.”

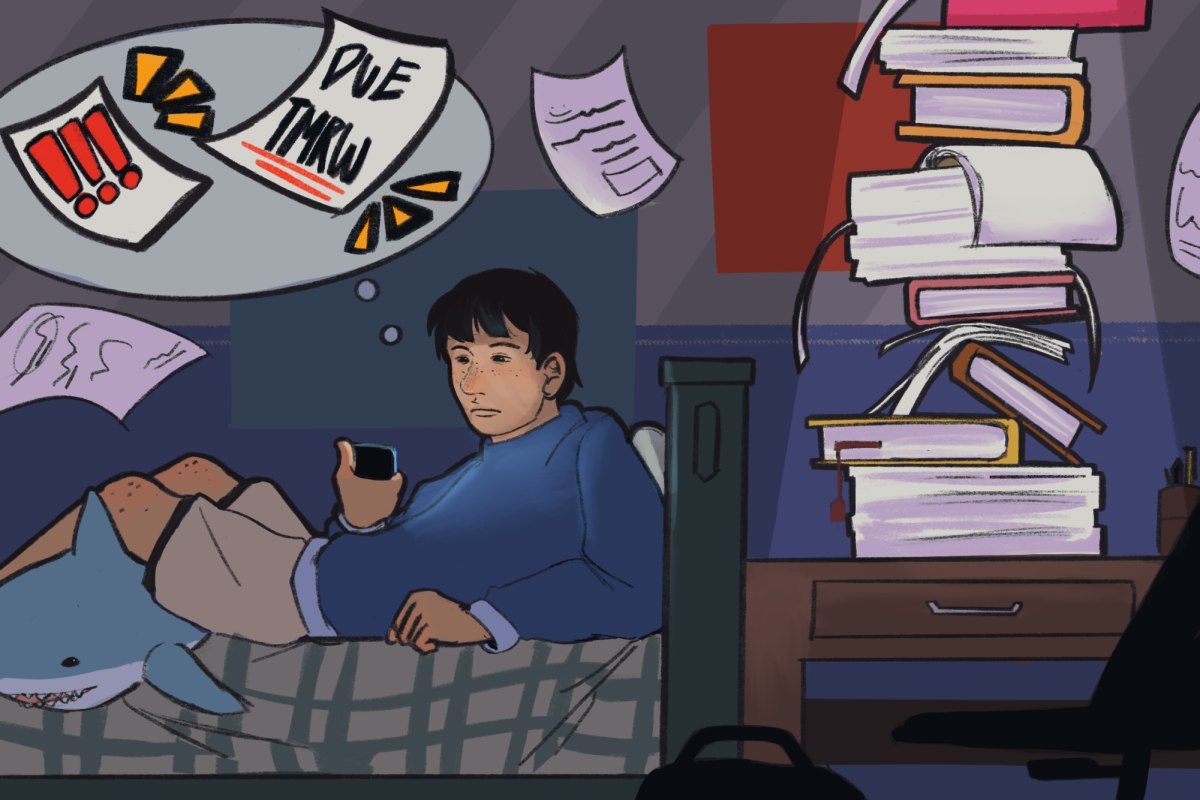

Lindsey’s daughter, Tatianna Banks, likewise, was never contacted regarding the creation of the show. She has described being unable to sleep and repeatedly seeing Dahmer in her nightmares following its release.

“I feel like they should have reached out because it’s people who are actually still grieving from that situation,” Banks said to The Insider. “That chapter of my life was closed and they reopened it, basically.”

The intense consumption of true crime dramas has also led to the sacrifice of journalistic accuracy among producers. Though “Monster” was directed through primarily victims’ perspectives, Anne Schwartz, the journalist who first broke the Dahmer story in 1991, has noted several inaccuracies, especially with the portrayal of Glenda Cleveland as Dahmer’s neighbor.

“In the first five minutes of the first episode you have Glenda Cleveland knocking on his door. None of that ever happened,” Schwartz said to The Independent. “I had trouble with buy-in, because I knew that was not accurate. But people are not watching it that way, they’re watching it for entertainment.”

Though a seemingly minute detail, producers often sideline ethics in order to sensationalize the coverage of heinous crimes. Outrage over police inaction towards Dahmer is well-deserved, yet the dramatization has contributed to increased conspiracy theories and true crime fanatics flocking to explore the clubs and apartments that Dahmer frequented, rather than a focus on the victims, which the docuseries intended. By fabricating scenes for dramatic flourish, producers blur the lines of reality.

“I think with something like this, you have to ask yourself ‘what is the point? Are we learning something from this?’” Illinois Wesleyan University psychology professor Amanda Vicary said.

This dichotomy between justice and entertainment also often contributes to negative long-term effects on the viewer. Those engaged in regular consumption of crime-centric content are more likely to experience physiological desensitization and decreased levels of empathy, according to a UAB doctoral study. Those who develop fixations on certain cases are also more prone to developing paranoia and stress-induced illnesses, says Cleveland Clinic psychologist Dr. Chivonna Childs.

“Watching true crime doesn’t make you strange or weird. It’s human nature to be inquisitive,” Childs said. “However, I always tell people that too much of anything is a bad thing, and when we watch too much true crime, we start to worry about the what-ifs. It can cause us to isolate and to not fully live our lives.”

It can be easy to get lost within curiosity and the desire to understand the unthinkable. Though, inquisition has been channeled effectively through podcasts like “Serial,” an investigative podcast into flawed prosecutions. A 12 episode series released in 2014 renewed interest into the case of Adnan Syed, a 17-year-old convicted for murder despite no concrete evidence. Syed’s conviction was overturned this month after 23 years. The key to its success? “Dogged reporting, a reliance on experts and propulsive storytelling,” says Barry Scheck, co-director of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit that targets wrongful convictions.

As viewers, It’s important to remember the “true” in true crime and separate dramatizations from reality. The often exploitative nature of true crime content taints it as a paradigm of justice, but it doesn’t have to be this way. With the sensitive nature of this material, audiences should critically examine the point of engaging in certain forms of it. And it’s safe to say that the Dahmer story can be laid to rest.

To check out another student publication’s take on this controversial issue, visit the Portola Pilot