Black history’s lack of depth in American schools

Black History Month celebrates the contributions of Black Americans while acknowledging the ongoing consequences of systemic racism. However, the fervent attempts by brands and politicians to capitalize on this time only draw more attention to the inadequacies of how Black history is presented, particularly in substandard curriculum through the states and uninformed calls for a ban on critical race theory.

A poll conducted by Monmouth University asked half of the poll sample about teaching “the history of racism” in public schools. 75% approved—amounting to 94% of the Democratic respondents, 75% of the independents and 54% of Republicans. The other half of the sample that was asked about teaching “critical race theory” in public schools produced only 43% support overall —ranging from 75% of Democrats and just 16% of Republicans. The reason for this discrepancy, despite how both questions are interchangeable, comes from the connotation of “critical race theory,” driven by partisan divides.

Conservatives tend to view CRT as an attack on white Americans, condemned by Republican politicians such as former President Donald Trump.

”Critical race theory [is] toxic propaganda, ideological poison, that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together, will destroy our country,” Trump stated at a 2020 White House Conference.

Similarly, Republican South Carolina Representative Ralph Norman called it a “cultural warfare,” as CRT “asserts that people with white skin are inherently racist…by virtue of the color of their skin.”

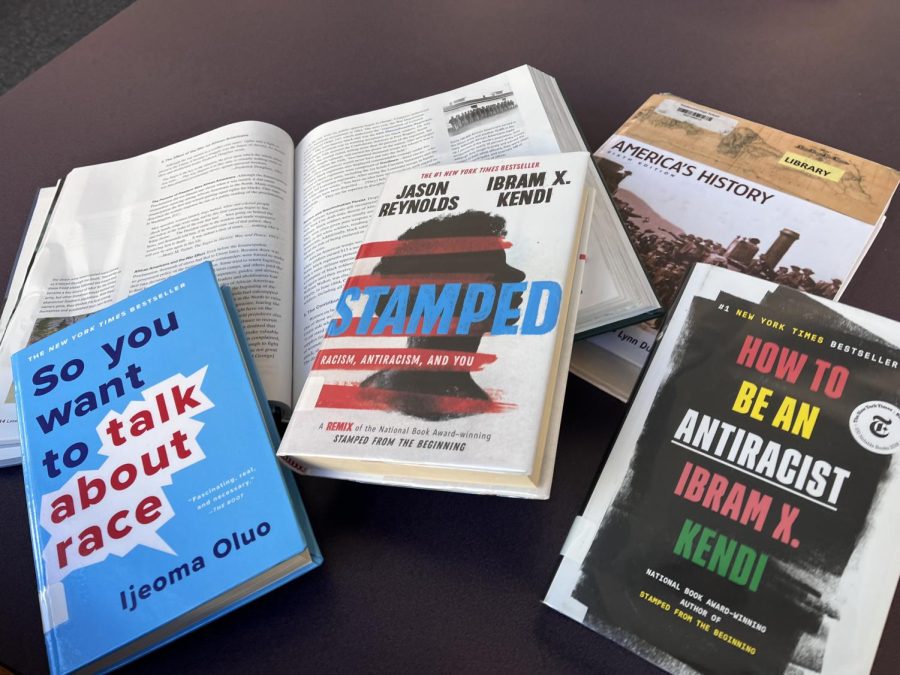

This narrative of supposed racist attacks against white Americans prevents education reforms from progressing with seven states having banned CRT and 16 attempts moving through legislation. The result of viewing CRT as “dangerous” manifests at the local level as educators fear the consequences when parents object. In Iowa City, after parents protested on social media, high school teachers stopped teaching a short story by Pulitzer Prize winner Alice Walker, a story involving a lynched Black man, to prevent further controversy. Another Iowan school ordered 1,000 copies of Ibram X. Kendi’s book “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You” for their U.S. history classes but it became optional reading after parents disapproved. This ignorant opposition to new beneficial resources proves how subpar education from earlier generations will continue if more measures aren’t taken to break the cycle.

However, over the past decade, there have been improvements in developing a comprehensive view of American history. Comparing surveys conducted by Pew Research in 2011 and by Washington Post in 2019 reveal a shift in how the Civil War is perceived, particularly by a young demographic of those under 30. In general, more people selected slavery as the main cause, growing from 38% to 52%. While those over 65 years were largely unchanged, from 50% to 47% selecting slavery, those under 30 shifted from around 30% to 58%. Claiming the primary cause to be states’ rights or economic conflicts negates the debates over slavery.

Racism was entrenched through the nation; although in the North there were those that were morally against slavery, there were others who only supported abolition to politically suppress the South. Conflict over slavery was driven by the economic differences between the industrial North that thrived with industries and the agricultural South that was dependent on plantations. But economics alone cannot explain the persistence of slavery, as even poorer white Southerners with no slaves believed the institution was an inherent aspect of the nation’s culture.

The roots of the Civil War play into how other eras of American history are interpreted, from Reconstruction, when Southern racism largely persisted in spite of emancipation, to the civil rights movement, when some ignorantly believe all racism was completely fixed with desegregation. How we view the Civil War particularly shapes our attitudes of race in the present, as denying the history of white supremacy prevents us from addressing it today.

The changing opinions of the younger demographic may be due to improvement of state standards such as Texas’ new history curriculum set in 2019 that directs students to “explain the central role of the expansion of slavery in causing sectionalism, disagreement over states’ rights, and the Civil War” when previously, these factors had been incorrectly taught as equally significant. Still, an investigation by CBS News found that seven states do not directly mention slavery in their state standards and eight states do not mention the civil rights movement. Only two states specifically mention white supremacy, while 16 states list “states’ rights” as a cause of the Civil War. This disparity of state standards is clearly evident when contrasting how identical lessons are phrased differently.

California: “Study the views and lives of leaders (e.g., Ulysses S. Grant, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee) and soldiers on both sides of the war, including those of black soldiers and regiments.”

West Virginia: “Compare the roles and accomplishments of historic figures of the Civil War (e.g., Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Proclamation, Gettysburg Address) Ulysses S. Grant, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Clara Barton and Frederick Douglass, etc.).”

Both of these standards involve learning about major figures of the Civil War but are drastically different in how they are framed. Although it’s undeniable that Jefferson Davis (Confederate president) and Robert E. Lee (commander of the Confederate army) were influential figures of the Civil War, the West Virginian standards calls to teach their actions as “accomplishments” which is an oddly positive connotation for those who were essentially traitors to the United States. Another difference is in how California emphasizes the role of Black soldiers but West Virginia leaves the inclusion of those lessons to the discretion of schools and teachers.

Perhaps the solution isn’t to provide a long list of every historical detail that must be covered, but to provide the resources for history teachers to explore various narratives. Curriculum should guide lessons, not dictate them. That means giving teachers a push in the right direction, say, by calling for standards that will teach slavery as the leading cause of the Civil War, but also how the mistaken states’ rights narrative came to be, by teaching topics like white supremacy and America’s aversion to confronting racism.

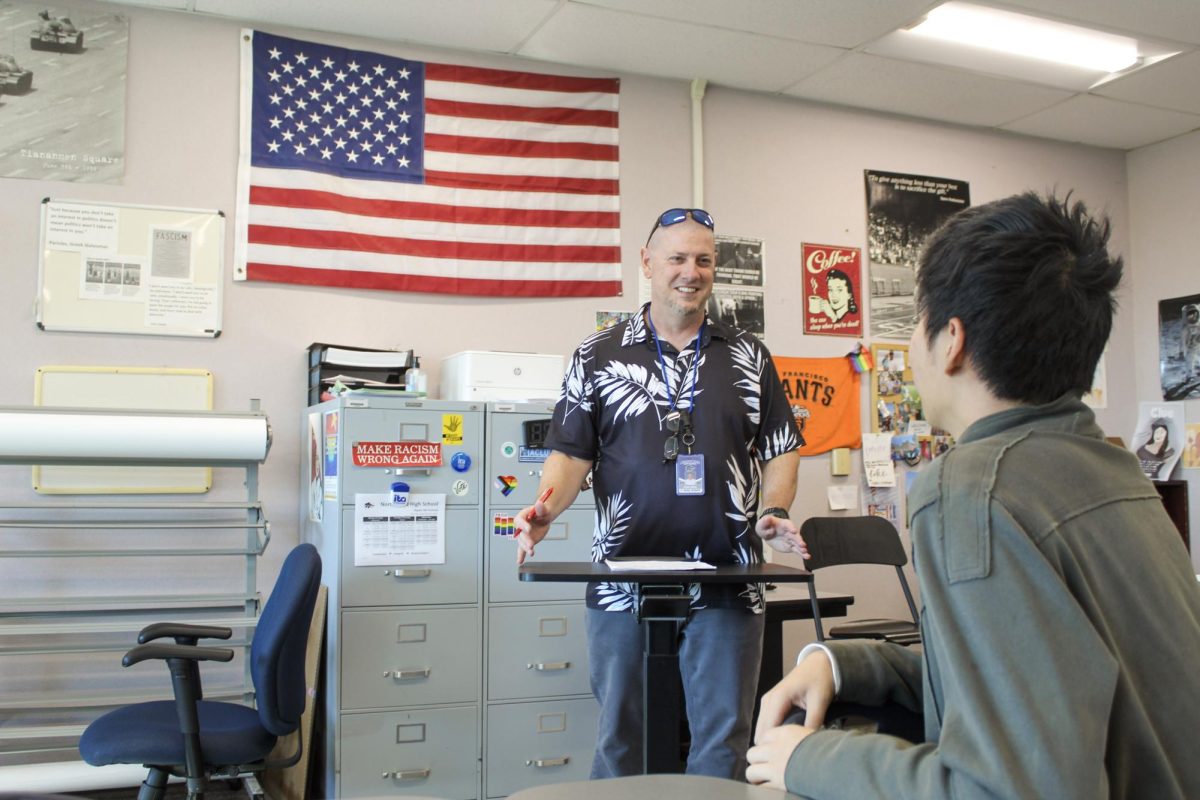

“I think California has done a good job recently focusing on skills so that teachers have more autonomy in deciding how we want to present standards to our class,” Northwood history teacher Anysia Leveratt said. “I enjoy teaching connections about present day issues so that students can start to see some of those impacts of historical events.The cool thing about teaching here is that I think a lot of the students aren’t aware of some of the bigger racial issues in America. It’s like, ‘Hey, open your eyes to someone else’s perspective to something else outside your own community.’ And I think the students here are really receptive to it.”

As all writers have some bias whichever way they lean, textbooks will never have a perfectly impartial recount of historical events, especially as there’s no way to neutrally sanitize the dehumanization of African slaves and its impact through every era of American history. Neither will social studies standards be perfect, but reforming them to guide often neglected lessons on Jim Crow laws and grassroots movements of the 1960s is a way to start. Accomplished Black figures extend far beyond the few martyred names spotlighted in textbooks, and it’s time to recognize the contributions of others such as medical pioneer Charles Richard Drew and NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson. For educators, this may mean incorporating more primary sources to allow students the opportunity for critical analysis rather than being fed information. For students, this may mean being open towards learning multiple facets of history, through proactively searching for supplemental material, not for the purpose of acing tests and completing homework, but to become a more informed citizen.

Rita is the Accent Editor for Northwood High School, and her favorite class...