Debating debate practices: Sexual harassment in debate

National Speech & Debate Association

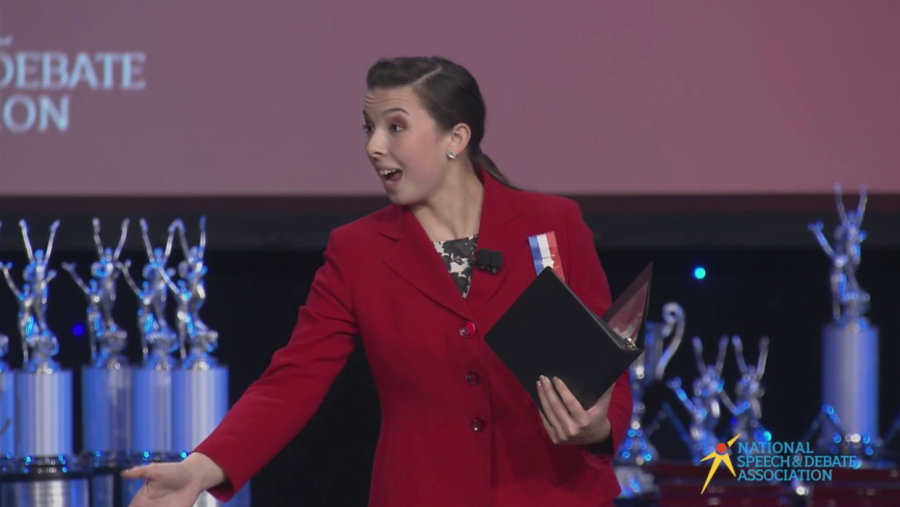

Women Deserve: Ella Schnake passionately performs her Program Oral Interpretation speech titled “Debate Like A Girl” at the 2019 National Speech and Debate Tournament finals—a reminder of the prevalence of sexism that impacts people in Speech and Debate and aids sexual harassment.

January 19, 2022

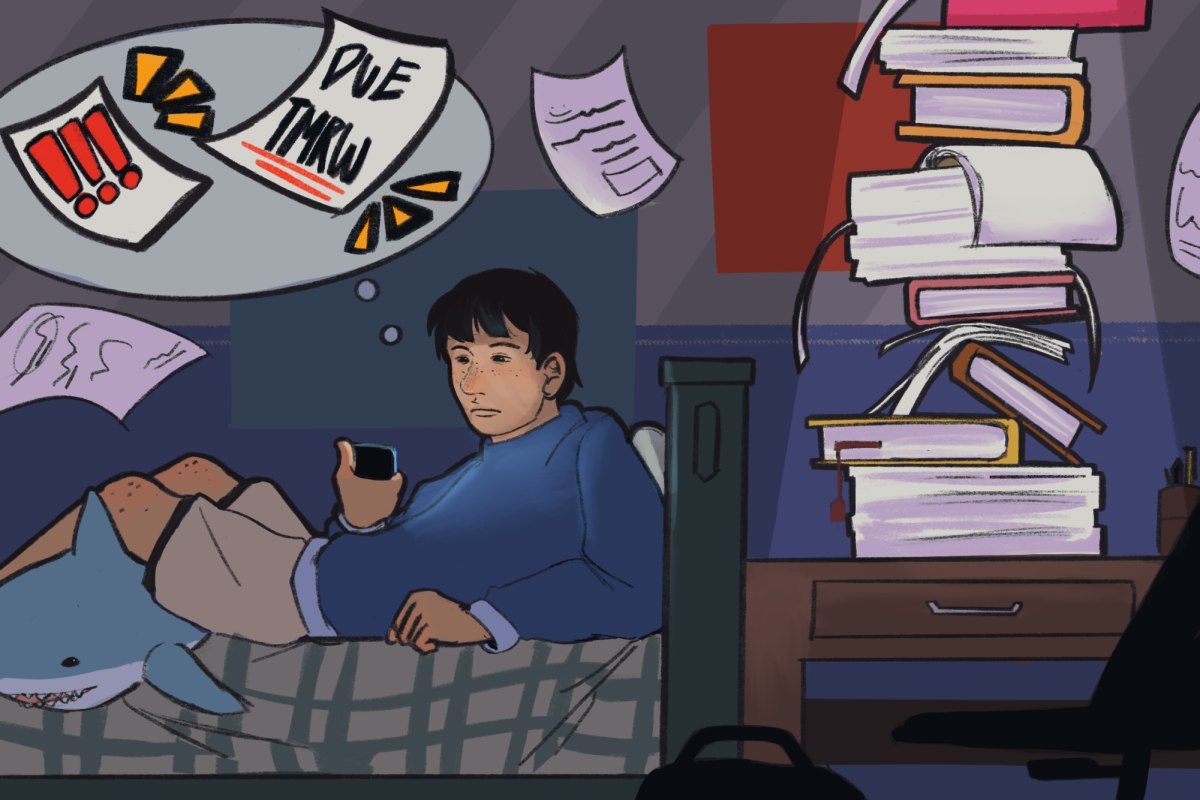

The timer beeps and the teenager in front of their computer sets off at a rapid pace, flying through their speech on water protection and nuclear war. Throughout the room, pens are scribbling down key concepts even as someone yawns and reaches for their morning coffee. Most debaters recognize that debate takes something from them—their weekends, their sleep or their computer storage. However, debate should never take away their safety.

I have been fortunate enough to be part of an amazing debate team that has the support of administration and other adults. However, some debaters are immersed in a breeding ground for violence and assault even when high school debate should, first and foremost, be a safe space for underage students to discuss, experiment and have fun exploring their interests.

Generally, like any other activity, female debaters already have a difficult time, given the sexism rampant in double standards for speaking (women are considered “bossy” or “arrogant” for speaking out, while males are considered “confident” for talking over one another), standards for attire (the insistence on wearing professional skirts to look put together) and more.

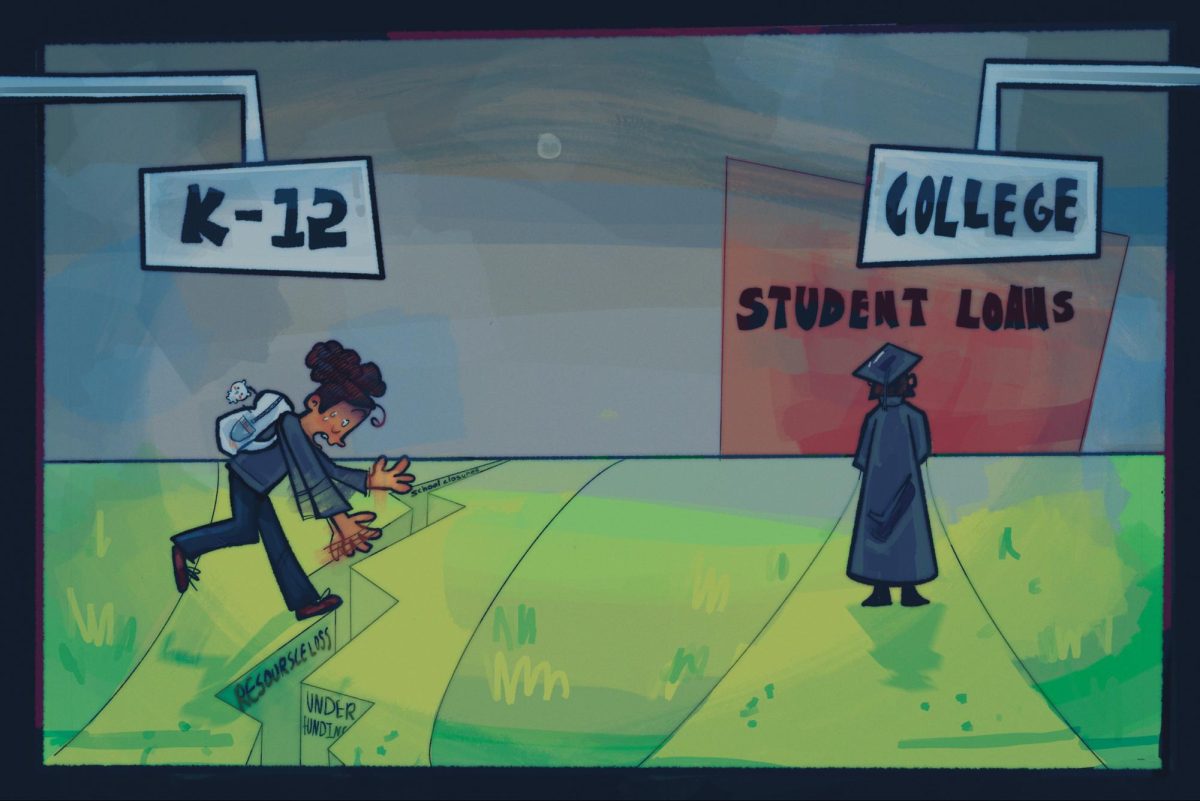

However, debate has evolved to form its own unique traditions and norms as well. The intense commitment that thousands of high schoolers across the country pour into this activity and community only magnifies this. For example, well-known, competitively successful (and often male) debaters are revered in what is known as the Good Debater Syndrome, which creates power dynamics amongst high schoolers that leave young women vulnerable to potential abuse. Speech and Debate Stories (@speechanddebatestories), an Instagram account that posts anonymous submissions regarding stories of discrimination and violence in high school debate, has over 400 posts regarding pedophilia, gaslighting, manipulation and more that happen both inside and outside of tournaments.

Even worse, adults can and often do contribute to such abuse rather than preventing it. Judges can not only provide the feedback that reinforces sexist standards (as mentioned above), but can also make young, underage debaters feel uncomfortable and unsafe when they are left alone in a room at a tournament with no supervision. Coaches, who are constantly teaching and advising underage debaters, can also abuse their own power. For example, prominent debate coach Jon Cruz was arrested in 2015 for asking for sexually explicit photographs from teenage boys around the country.

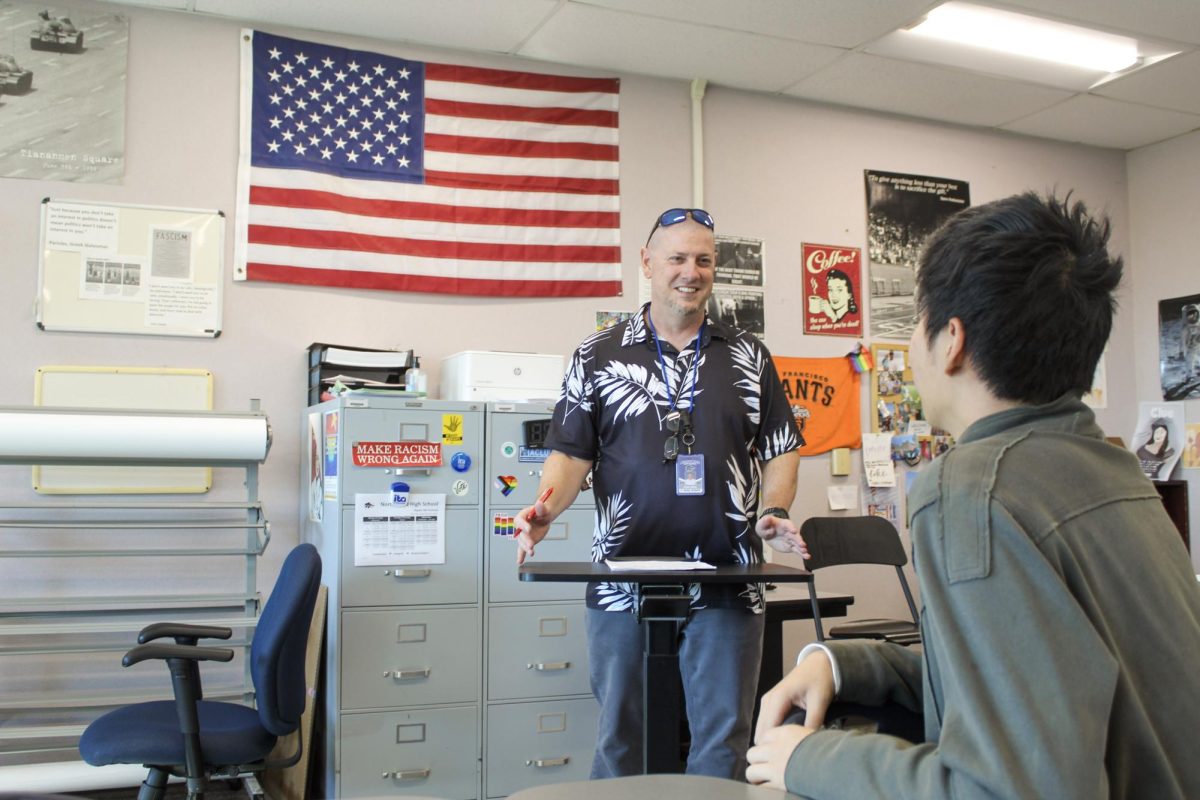

The circulation of such stories is undoubtedly a positive sign because it demonstrates an effort at transparency in debate. When I started debate in high school, I was similarly impressed by what seemed to be a constant discussion over accountability and the inequities of the activity, spanning across different online platforms. As an example of this, Northwood Speech and Debate recently held its first Equity Day initiative, where the team split up into small groups to hold discussions regarding the personal experiences and observations of unequal treatment.

“I feel that Northwood is very inclusive in terms of the club itself,” sophomore Anika Akshantala said. “It felt like there was an event for everyone regardless of experience, skill and to an extent, financial resources.”

However, while such awareness is encouraging, adults in charge of competitions need to do more to make debate a safe space. Reforms focused on regulating other adults have been offered numerous times by people within the debate community, such as a petition for a new ethics code from the National Speech and Debate Association (the institution that governs most of the Speech and Debate activity nationwide), a system to report sexual misconduct and a process of accredition for coaches and judges. The National Speech and Debate Association has already committed to some, such as judge training for its judges and anti-harassment training for its employees.

The National Speech and Debate Association, however, can only encourage all tournaments to follow its protocol. Every tournament director must bear the responsibility of creating basic judge screening processes and reporting systems after they are standardized by the National Speech and Debate Association. Current forms of training, which are typically asynchronous, functionally optional videos that judges are encouraged to watch, can also be reinforced by simply requiring all judges to take a short quiz or some other measurable test of the protocol’s effectiveness prior to judging. Along with the National Speech and Debate Association, the University of Kentucky (the university in charge of awarding bids to tournaments) can condition a tournament’s ability to receive a bid—a qualifier that is often a mark of a prestigious tournament—on such action. This would also send a signal that the safety of competitors is prioritized over the prestige of the tournament.

New policies will be strenuous and require significant effort on the behalf of all involved, from judges to tournament administrators. However, they will be well worth the effort if there is any possibility of remedying a serious problem that is detrimental to the safety of debate and the debaters that suffer because of it.