Racial Inequities in COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution

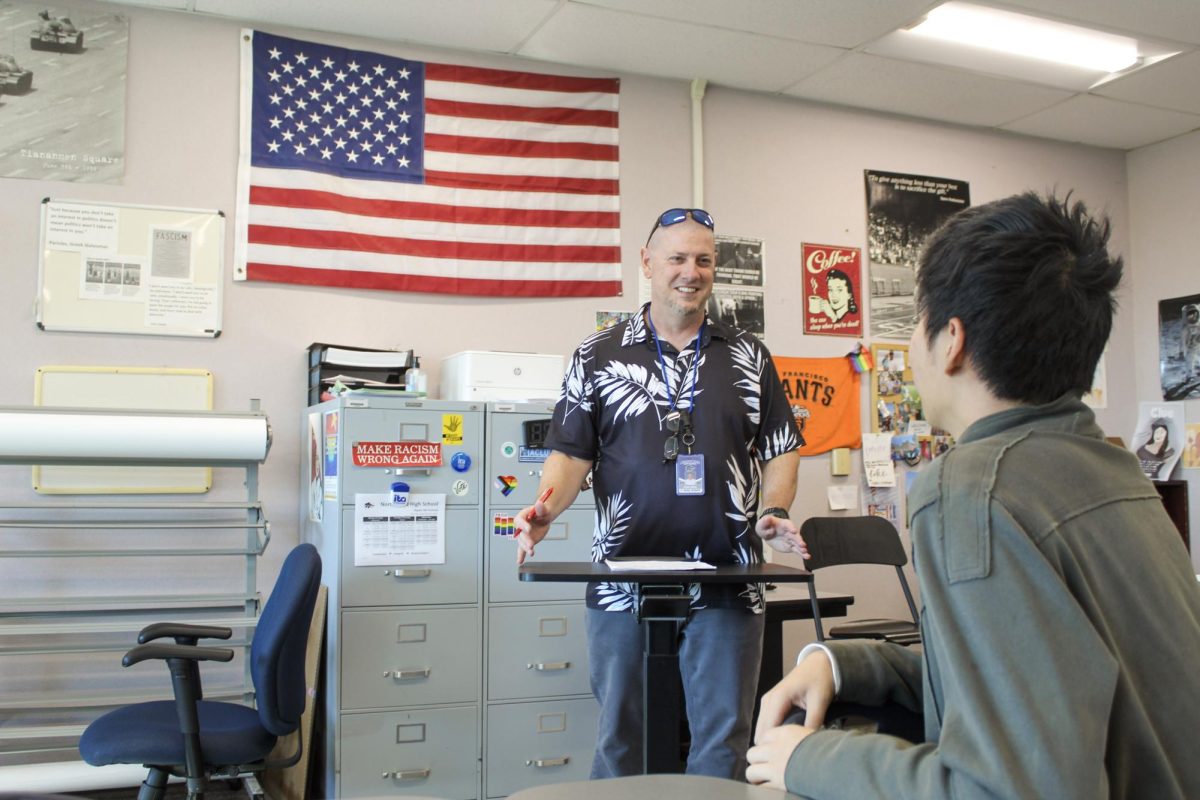

IMBALANCE: COVID-19 shines a spotlight on the flawed healthcare system in the United States.

March 9, 2021

How do you choose who lives or dies? In the summer of 2020, the United States witnessed social movements for racial equity overlap with the destruction of the COVID-19 pandemic. As large numbers of vaccination doses roll out, we seem to increasingly witness greater relevance between the two.

As vaccination spreads in availability, a greater gap has formed within American communities, tearing the United States into those who are able to get the vaccine and those who are not. Data shows that in most states, Black and Hispanic individuals receive a significantly smaller portion of available vaccines in comparison to their population proportion and their share of cases or deaths caused by COVID-19. For instance, Black individuals have received only 15% of Mississippi’s total vaccination doses, despite making up nearly 42% of COVID-19 deaths in the state. Other minorities including Native and Hispanic populations are facing similar disparities. With Black, Native American and Hispanic COVID-19 death rates nearly three times those of their white counterparts, the disparity in vaccine accessibility reveals a larger system of inequity not only particular to COVID-19 vaccines but rather the entire healthcare system and the United States as a whole.

The issue primarily stems from a number of deep-rooted factors ingrained into the racial injustices of the United States. Among healthcare workers alone, people of color face significantly less access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and are much more likely to face greater exposure to COVID-19 patients to a clinical setting. Upon analyzing antibody evidence of previous COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers, the CDC concluded that healthcare workers of color faced higher rates of seropositivity than their white colleagues, suggesting higher likelihood of prior infection.

Structural inequality has created even greater disparities in the general population as Black individuals face greater rates of contraction and death in nearly every state. Throughout the 20th century, redlining—an unjust practice of services that discriminates against residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity—has segregated racial minorities, particularly Black communities, and trapped them from earning higher education, buying homes and accumulating wealth. Black communities are also typically areas of greater population density, increasing the rate of COVID-19 transmission compared to more affluent, predominantly white regions. While facing both higher dependence on public transport and reduced access to hospitals or equitable healthcare, Black workers represent a larger proportion of the COVID-19 essential workforce—bus drivers, food service workers, cashiers, etc. A history of discriminatory treatment against racial minorities has also fostered a deep distrust of the medical community of the healthcare industry. With reports of police stopping Black PPE-wearing healthcare workers in stores and openly coughing at Black residents in a public housing complex, the Black community faces a number of racial biases that shape disparities in healthcare.

As COVID-19 vaccines increase in availability, we can hope to see inequities reduce as states are increasingly recruiting vaccinators in local neighborhoods through the CDC’s social vulnerability index, which interprets race, density of housing and poverty, as the Biden administration hopes to establish more racial equity for the vaccine rollout. But even after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides, the United States will continue to face greater racial injustices that may take more than a two-dose vaccine to eradicate.