Minari: A forgotten voice waiting to be heard

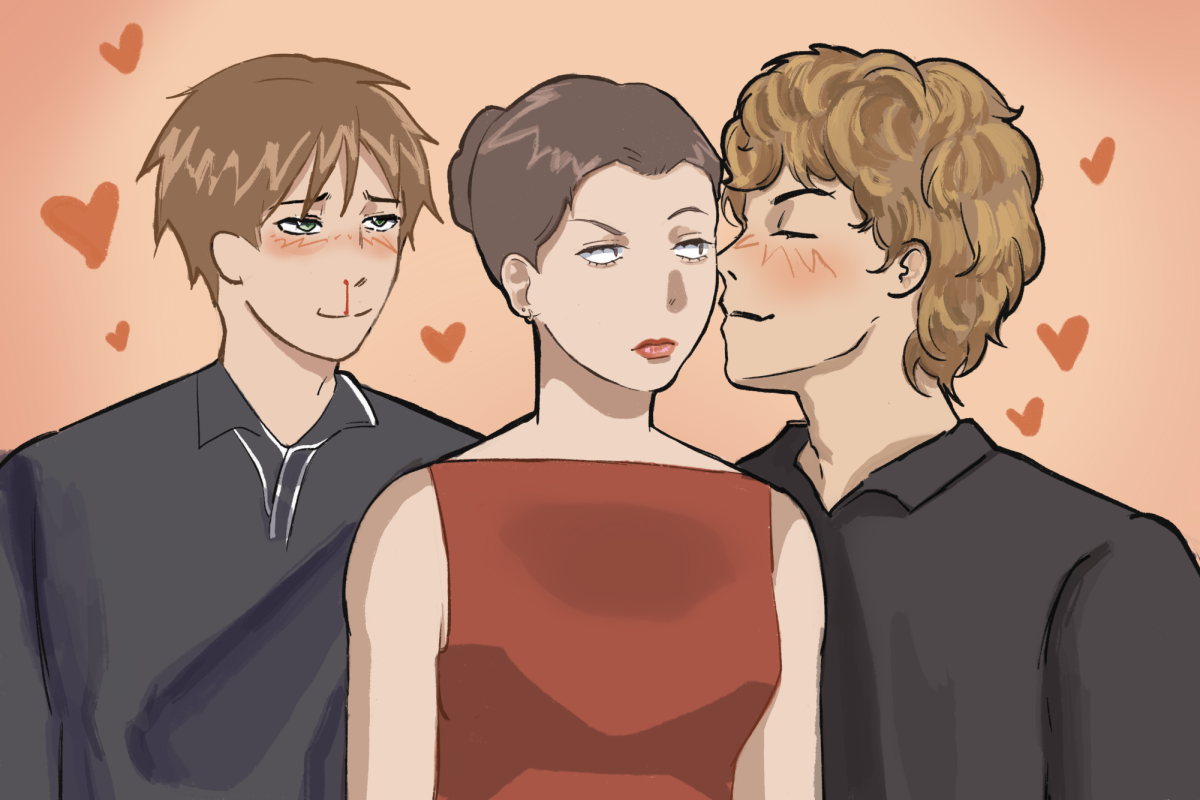

THE SUCCESS TO FARMING: After rejecting an offer to purchase a divining rod to find water, Jacob teaches his son, David, where they should dig for water, which is needed for farming.

March 3, 2021

It seems almost unimaginable to discuss Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari” without mentioning the numerous nominations and awards the film has received, and its controversy for not being eligible for the Best Picture category at the Golden Globes.

However, since these important issues have already been discussed to great extents, movie viewers should focus on the story at heart. “Minari” is about a family surviving in an unexpected environment they must soon learn to call home, a comforting story that, although centered on immigrants from South Korea in the 1980s, many can relate to.

The film begins as Jacob (Steven Yeun) and Monica Yi (Han Ye-ri) bring their children, Anne (Noel Cho) and David (Alan Kim), from California to Arkansas hoping to find success through farming. While Jacob is overly optimistic, Monica is doubtful and David and Anne seem to be unaware of their parents’ concerns.

Monica’s mother, Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung), soon arrives from South Korea. At first, David is uncomfortable around her as she seems to be doing all the wrong things: calling him “pretty” instead of “good-looking” and not being able to bake cookies. But eventually, she forms a loving bond with David and begins to plant minari, a leafy vegetable often used in Korean dishes. While planting the seeds, she explains to David that minari is resilient and will grow anywhere, the theme of the film.

After Soon-ja plants minari, the family only revists it at the end of the film. Yet, the minari survives even without Jacob’s care, symbolic of South Korean immigrants. Planted in a foreign environment, they carried the stereotype of being submissive for decades and lived without much attention or help from society.

Beyond resilience, “Minari” is about parental sacrifice, another aspect that made the film so relatable. Each of the parents makes a conscious effort to create a better life for their children: Jacob and Monica work and Soon-ja leaves the comfort of her home to help her daughter. With the difficulties Jacob faces in his relationship with Monica and his efforts on the farm, the film adds another layer of complexity that makes the audience question what the American dream truly means and how pursuing one’s passion can potentially impact the rest of the family.

What made the film so personal was that it was based on the true story of director Lee Isaac Chung and his memories growing up on a farm with his parents. But Chung made many efforts to prevent his personal memories from getting in the way of the creative process, an example being how he changed the family name from Chung (his own name) to Yi.

“I think one of the things that I had to establish for myself quite early on was the rule that this is not my parents and this is not me or my family, that somehow this has to become a family that exists solely in the film of Minari,” Chung said in an interview with the National Public Radio. “Once I [changed the name], I really invested in that idea and gave myself the freedom to just let them be themselves.”

Because of Chung’s choice to prioritize creative freedom, the actors and actresses took measures to make their characters come to life. For example, Han revised parts of the translated script to make it sound more natural in Korean. And Youn worked with a neurologist to make sure she was moving only certain parts of her body during the scenes when Soon-ja has a stroke.

In addition to the exceptional efforts from the cast, the details of South Korean culture embedded in “Minari’” add authenticity. By mentioning everything from the traditions of a patriarchal household and society (like when Monica was unaware that they would be living in a mobile house) to attending church to the theme of parental sacrifice, the film alludes to several customs that both first and second generations of Korean Americans can relate to.

Unlike many blockbusters, a majority of the film isn’t very dramatic. There isn’t a turning point when a hero sweeps in to save the day; no one can save them except themselves. For some viewers, the film may feel very uneventful, but this is the advantage of the storyline. With the calming atmosphere of the farm and melancholy music, the focus remains on the relationships each character maintains throughout the film.

Without relying on tropes, the tear-jerking moments or cliche storylines, “Minari”’ tells a forgotten story of survival, proving once more that the greatest strength of an indie film is its ability to resonate in the hearts of the audience.