The College Board’s Failure with AP Tests

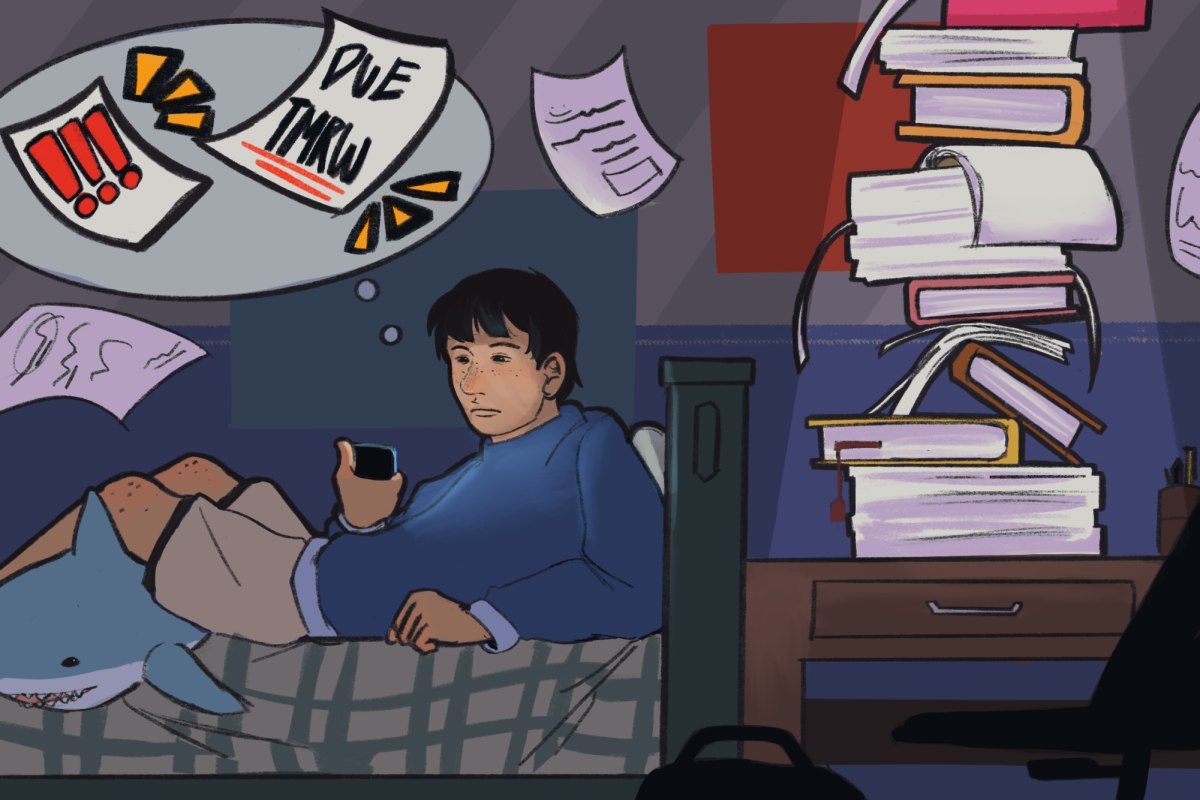

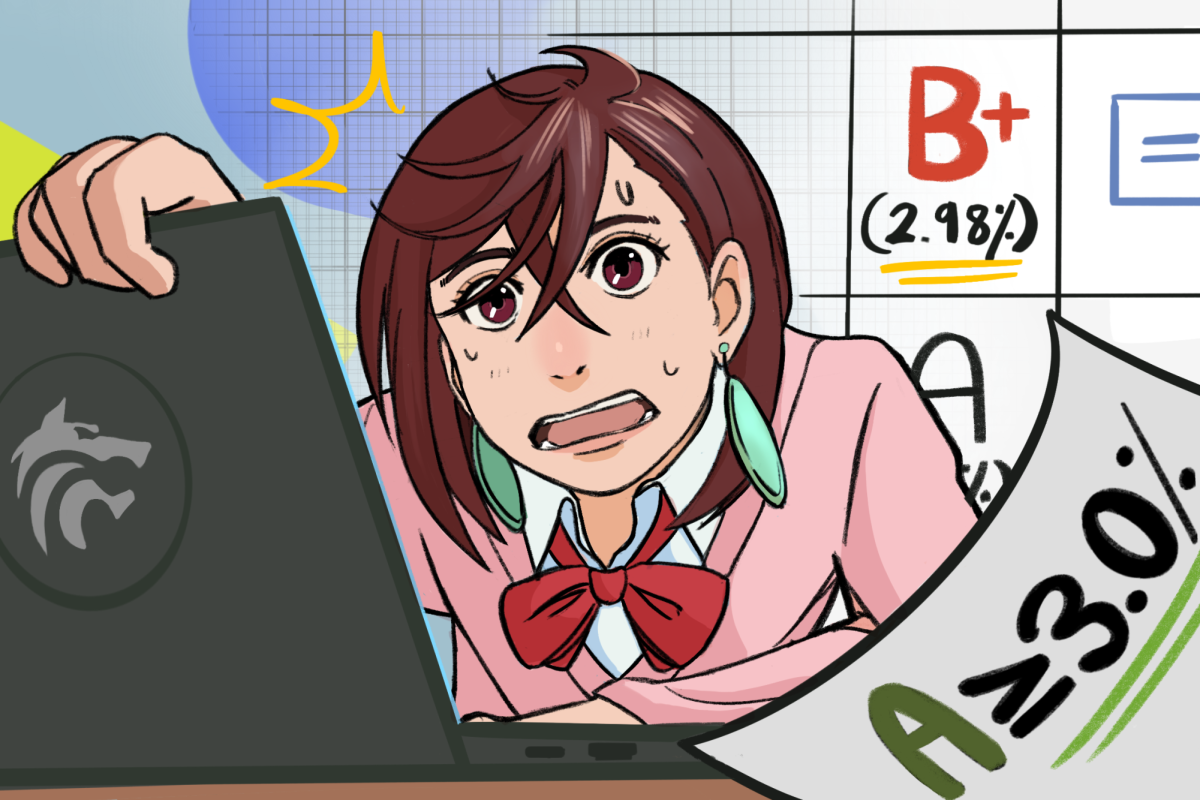

TEST DAY: Students take AP exams on test day after a year of studying.

January 28, 2021

As one of the foremost ways of showcasing academic excellency, Advanced Placement (AP) tests have become a substantial component of college admissions. Not only do they prepare students for college, but a high score can grant college credit, helping students pass out of general education classes and therefore saving money on tuition. However, in failing to address problems with testing this year, the College Board has created a problematic, if not unethical, year of testing.

The primary issue with AP testing is a lack of consistency between different regions. Despite ostensibly advocating for in-person testing for all students, the College Board hasn’t accounted for the unpredictability of COVID-19, leaving the actual testing method ambiguous. For instance, Norton County, Kan. has 5.3 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 people according to The New York Times, as opposed to 107 cases per 100,000 people here in Orange County. Different regions have different requirements for safety, so generalizing testing regulations for all counties can be dangerous.

Although the College Board has a contingency plan for communities with rising cases, this adds even further complications. The plan will likely consist of online testing, which can increase economic disparities by favoring higher-income students.

“Among lower-income adults, 46% say they have had trouble paying their bills since the pandemic started,” a Pew Research Study states. “About one-in-five or fewer middle-income adults have faced these challenges, and the shares are substantially smaller for those in the upper-income tier.”

Lower-income families may not have the ability to purchase necessary technology and may opt out of taking tests in order to sustain their families, negatively influencing their college applications and reducing potential college credit. This effect is hardly present in higher-income families, implying that the admissions process could be further skewed to favor high-income students.

Another important issue is the testing material. All tests will cover the same amount of material as a regular year, meaning three hours of testing. For such an irregular year, maintaining test length can grant certain students advantages, since in-person testers may get access to materials such as calculators and equation sheets that make testing easier. Additionally, concerns of cheating are naturally higher for online tests, as students have a much larger window than the 45 minutes last year to access outside resources. Since the pandemic has reduced time in classrooms, teachers are also concerned about covering all of the material in time for the test in May.

On top of all this, regular concerns about online testing still persist. Last year, some students were unable to submit their answers before the deadline due to latency issues, voiding their results and forcing them to take the exam at a later date. For a three-hour test, this is especially concerning, as a WiFi outage in the middle of a test can prevent students from answering questions, lowering scores significantly.

Although these are difficult issues to solve, the College Board can address them by implementing new policies. The first and most crucial change they can implement is transparency with students and teachers alike. By announcing a decided method of testing earlier on in the year, the College Board can prevent potential surprises and inequities.

Another change should be reducing the amount of material tested. While students do have an entire school year to prepare, the pandemic has greatly reduced class time and access to important materials, meaning a cut in the tests can provide a more equitable standard of education.

The College Board plays a crucial role in college admissions, and their complacency can damage entire communities. They should take responsibility for their faults and value students over profit.