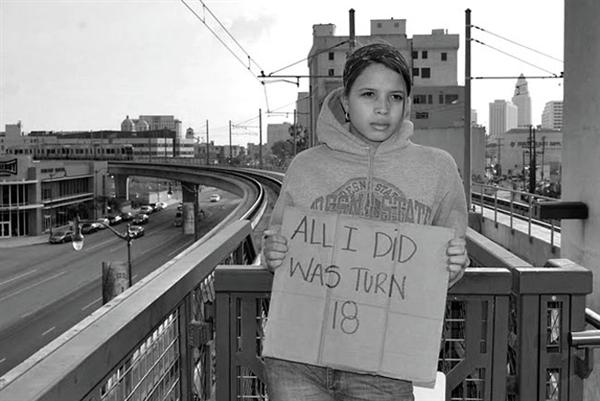

No Place like Home: The US Foster Care System is Broken

As teenage foster youth age out of the system, they are thrown into the adult world without an adequate system of support.

October 20, 2020

On paper, the foster care system is picture-perfect. A neglected child is lifted up from a broken home, plagued by abuse and mistreatment, to then be gently placed in a warm, welcoming environment with safety and stability. In reality, this picture-perfect cloak disguises disastrous failures that leave children vulnerable and defenseless.

The majority of children in foster care come from environments of abuse and neglect typically created by biological parents who have fallen victim to drug addiction, incarceration, or death. As the opioid epidemic continues to escalate, the need for foster parents is greater than ever. Research from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that 2019 was the fifth consecutive year in which the number of children entering foster care grew. States are increasingly experiencing an acute shortage of competent foster parents and scramble to find places for the hundreds of thousands uprooted from their homes. This national crisis in the search for foster parents stems from inadequate training and a lack of support that drive approximately half of all foster parents to quit fostering children after their first year.

Plucked from their homes with no place to go, thousands of children are sent to juvenile detention centers, shelters and group homes—all locations agreed upon by child welfare experts as the ultimate last resorts for a child’s growing environment. Isolated from the outside world in cold, harsh facilities with little social interaction and treated as criminals, foster children in congregate face conditions not much better than the ones from which they were removed. These children often jump from shelter to shelter, uprooted by the lack of sufficient resources in care centers, and have even been called by child advocacy experts as “homeless in foster care.”

In just Washington state alone, more than 2,000 foster children have had to stay overnight in hotels due to a lack of housing provided by the foster care system. In 2019, a few slept in the offices of their own social workers. Oregon has also placed children in refurbished juvenile centers and former police stations concealed with new decor.

With these dreadful conditions, it’s no surprise that many foster children are desperate to get away from the system meant to help them. In 2013 alone, over 4,500 foster youth ran away from group facilities or temporary shelters. When children feel so guilty and unwanted by a system meant to protect them that they end up running away, it is strikingly clear that the system is deeply flawed. Children who are placed in hostile settings like juvenile detention centers are given the impression that they themselves must have done something wrong, ingraining in their minds the idea that the system is not meant to help, but rather punish.

As such instability shakes already-vulnerable children, many are pulled further away from resources that invest in their long-term futures. Roughly half of foster youth nationwide never graduate high school and even less than half are able to earn money from employment at any given time. One in five will enter the homeless population and one in four will become involved with the criminal justice system within just two years after foster care. After years of trauma of being passed from place to place with as much instability as the original home of abuse, 21 percent of former foster youth develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, as opposed to a mere 4 percent of the general adult population.

The foster system produces such weighty statistics because most foster youth age out of the system without a reliable system of support built through a connection with a permanent, stable family. Children in the system are therefore deprived of the bonding experiences that shape their childhood and, consequently, their outlook in adulthood.

The foster system also displays another troubling phenomenon: although the statistic of child abuse and neglect for black families is lower in proportion that that of white families and black children represented 14% of the total child population, they make up 23 percent of the foster care population. In comparison, white children, who represent 50% of the total child population, make up only 44% of the foster care population. As racial minorities are disproportionately placed into the foster care system and become targets of its immobilizing conditions, the socioeconomic achievement gap afflicting the nation’s education system is further expanded.

As a result of multiple flaws deeply embedded into both our federal legislation and societal tendencies, the foster care system undoubtedly fails children who need a secure environment and in some cases may abandon them in a deeper ditch than their origin. Because the flaws in the foster care system are caused by an interlaced network of external issues, there is no perfect solution. Federal initiatives like the Family First Prevention Services Act work to fund services meant to keep children out of foster care, but they do so by eliminating current group care centers and thereby displacing thousands during a time of a foster family shortage. However, a series of diverse legislative and social implementations may help take a step further in the direction.

First, legislation must take a substantial number of measures to fight the public stigma about foster children that discourage many from becoming a foster parent. The stereotypical confinement of foster children as troubled delinquents and charity cases portrays foster parenting as an incredibly challenging, purposeless experience that forces the public to view foster youth differently than for what they really are: normal children who simply deserve a chance. As the number of children in foster care continues to increase, the shortage of foster parents must decrease so innocent children aren’t forced to live in harsh, deplorable conditions. A greater connection of resources and support have to be provided for foster parents to raise the retention rate so children aren’t left isolated after their first year.

Second, the preservation or reunification of the family of origin must be prioritized when ensuring the child’s safety and well-being. Although connecting a child to their abusive family is never acceptable, the federal government must fund more resources to help protect families that do want their children. Separating families creates trauma for children in foster care and further perpetuates the instability in their lives. Providing assistance to biological parents and families will serve as a first step towards breaking the generational cycle of abuse and neglect.

“I didn’t have hope before,” Kendra, a biological mother who once lost her sons to foster care because she turned to methamphetamines after the death of her grandmother, said. “Now I have hope, and both of my sons are home. When they call me mommy, sometimes I cry because there was a time that might not have happened. It’s the best feeling to get to be their mom, like I should have been.”

Cj

Feb 5, 2024 at 10:06 pm

The system has a lack of foster parents because the system treats foster parents terrible. As a foster parent my wife and I have tried to adopt at risk children multiple times. Every time the system would prolong the process of adoption and give undeserving family members an endless amount of opportunities for placement. Kids go back into bad family environments, then in a couple months get rotated back to foster homes. During this whole time the foster parents who love and want to adopt the child are always seen as a last resort. By the time the legal process ends, kids age out of the system or spend most of their childhood never being adopted or adequately cared for.

Adryan Gregg

Dec 26, 2023 at 3:46 pm

This is great for my research on “Flaws In The Foster Care System”

Barbara Foreman

Aug 28, 2021 at 8:38 pm

You did a great job written this. I also was a foster kid now working on reform. We got a small group kayla’s apples. If you would like to join. We would love your out of what needs to take place. We have been meeting with sentors.

Linda Bullock

Jun 3, 2021 at 5:39 am

I have a question about the foster care system. Do the biological parents receive a monetary bonus? for agreeing to take their biological children out of a foster care home(which may prove to be the safest and more loving home for the children)? If this is happening, how can anyone be sure the biological parent is doing this because they are truly wanting to change and take proper care of their child?

CJ Pittz

Nov 15, 2021 at 9:16 am

As someone in the foster care program I know that the parents have to go through multiple programs and if they relapse they have to restart. the biological parent cannot take the child out unless the government approves it.

dylan

Feb 9, 2022 at 9:48 am

so what i’m understanding is that the gov. and foster system don’t care as much if the child is being abused ect but they care more about if it’s safe or not for the parent to raise their child? sorry if that doesn’t make sense

Fern

Dec 9, 2021 at 4:45 am

The biological parents receive no bonus. The State actually receives cash bonuses for every child that is placed into foster care and adopted out. This creates a huge problem with some States placing profit over recertification.

dylan

Feb 9, 2022 at 9:49 am

it seems that gov and foster care system cares more about the cash over the child in a lot of cases.

Alena Cordeiro

Oct 11, 2022 at 6:16 pm

Thats exactly what they care about.