With students’ increased reliance on artificial intelligence, teachers’ jobs have become significantly more challenging. At Northwood, the academic honesty policy prohibits plagiarism, including through the use of AI without “explicit instruction” from teachers. However, actually determining whether students used AI is a tough process.

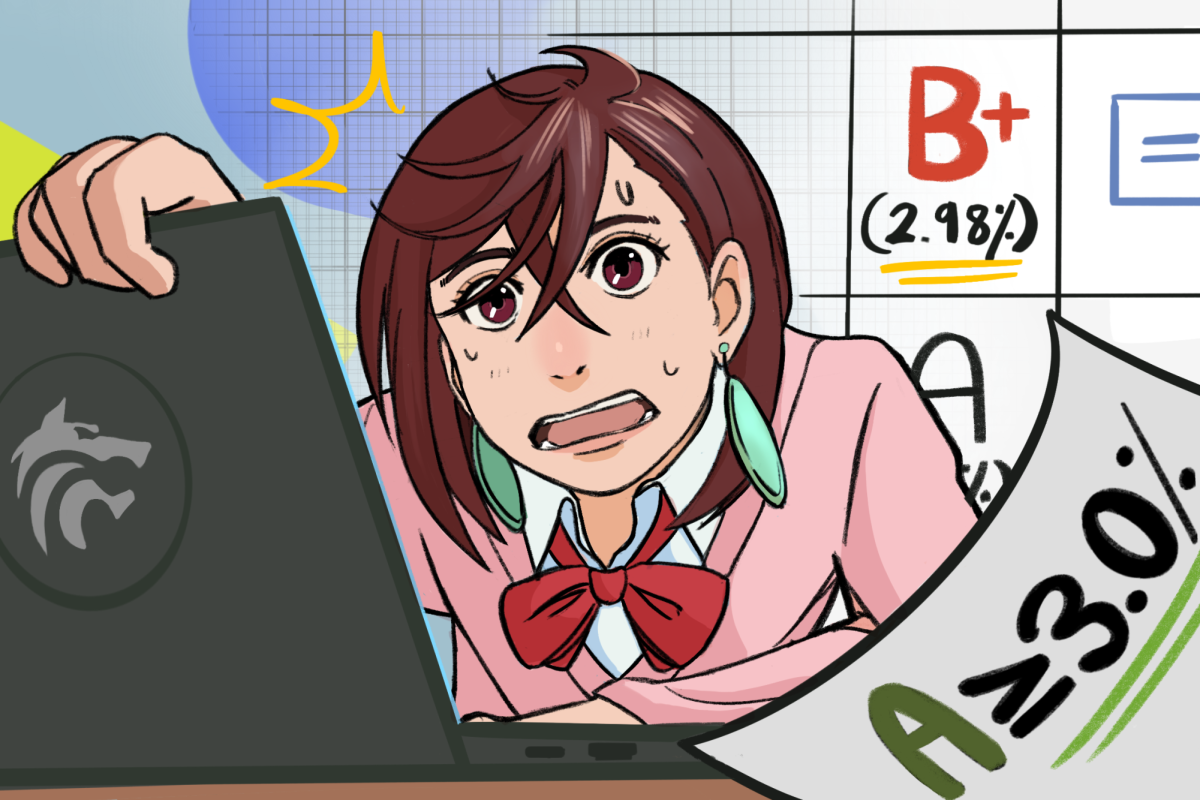

Many are familiar with Turnitin’s AI writing detector, which provides teachers with a similarity report that highlights the percentage of a student’s work that may be plagiarized. However, it does have its flaws, with the platform often detecting false positives or flagging work as AI-generated when students use extensions like Grammarly.

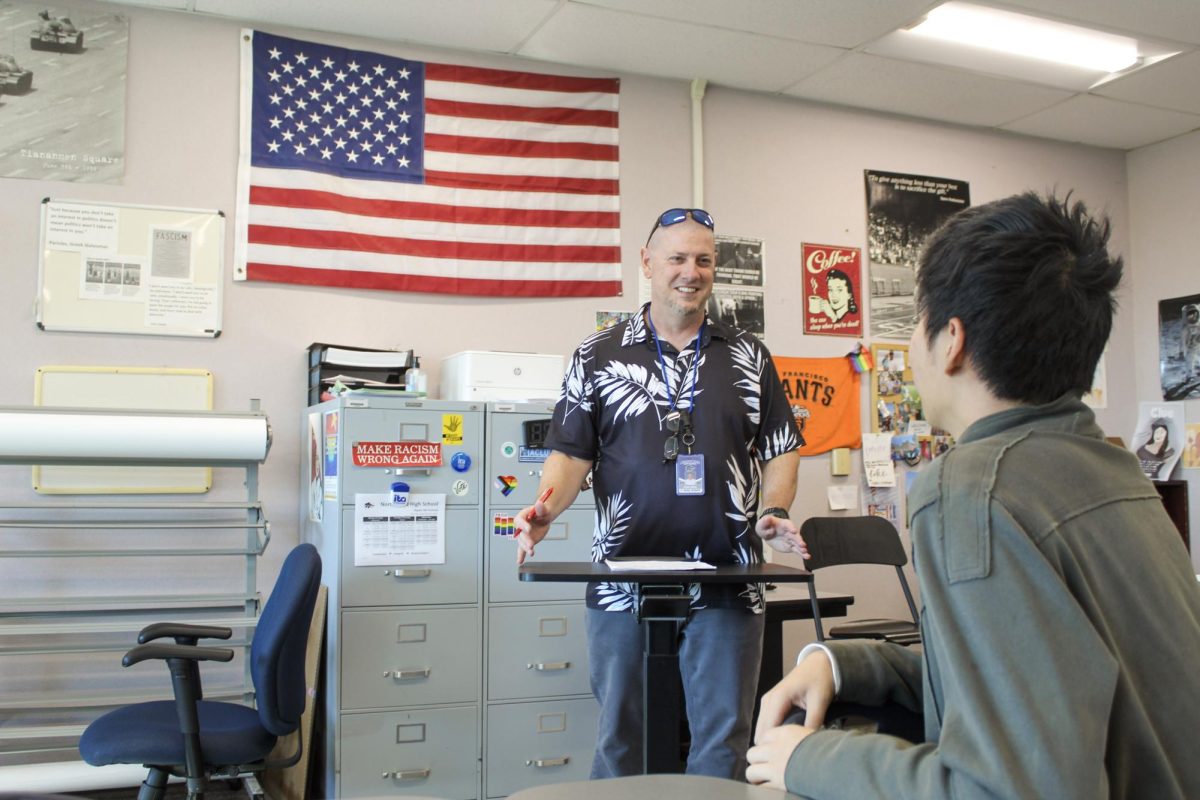

If a student is flagged for AI use, teachers will bring the student in for a conversation to discuss the integrity of their writing.

“As opposed to being accusatory, [us] teachers know that we’re working in a very gray area, and we just want to make sure that we’re getting the full picture before jumping to conclusions,” English teacher Sarah Riggan said. “It is really tricky, though, to discern what is student work versus what is the AI-polished version of the work.”

Still, students express concern about this evaluation process.

“Submitting work through Turnitin is stressful because I think it’s pretty unpredictable whether or not I’ll get flagged even if I didn’t use AI, and it would be kind of hard to prove myself to teachers who probably think I did when they see a percentage,” junior Elyse Wong said. “My biggest concern is ruining that trust I have with my teachers if they think I’m lying.”

To reduce the risk of incorrect flagging, teachers are trying to isolate student voices through on-demand, in-class writing assignments where students produce work without technology assistance, unless required for translation services.

“I do think that you can kind of evaluate that writing with some of the other writing they’ve done and see, ‘hey, this does not sound like that student,’ and I think that makes it easier to determine whether AI was used,” English teacher Derek Roche said.

Similar to the English department, most summative work in science classes, like models or CEJS, is done in-class. While all teachers have access to Turnitin, some science teachers choose not to use the program. Instead, pay attention to a student’s growth in their drafted initial scientific ideas to their final product.

“We ask students to show their work—show your thinking, show evidence of your thinking, justify your thinking,” Science teacher Gabrielle Kim-E said. “So even though a response looks good, it makes sense, but ‘how did you get there…’ so we’ll expect some sort of evidence and how they got to that answer.”

Currently, teachers are still figuring out if and how AI can be used responsibly in their classrooms without sacrificing students’ critical thinking skills. Staff members formally discussed AI usage but haven’t fleshed out a policy that’s fair for every discipline due to the differing expectations for each subject, according to English teacher Sara Katlen.

The best way for students to avoid getting flagged is to turn off any AI features on their devices. Teachers ultimately want students to produce authentic work that reflects their own capabilities.

“I just want students to understand that nobody expects you to be perfect—that’s an unfair expectation,” Katlen said. “I think there is such a sense of pride and accomplishment that comes from authentically doing something and then learning how to do it better. That’s empowering.”