Special education teachers at Northwood—as well as throughout the district—are dealing with heavy workloads and high expenses related to their profession.

Thus, staff members with special education credentials should be provided with stronger contract protections to address these issues.

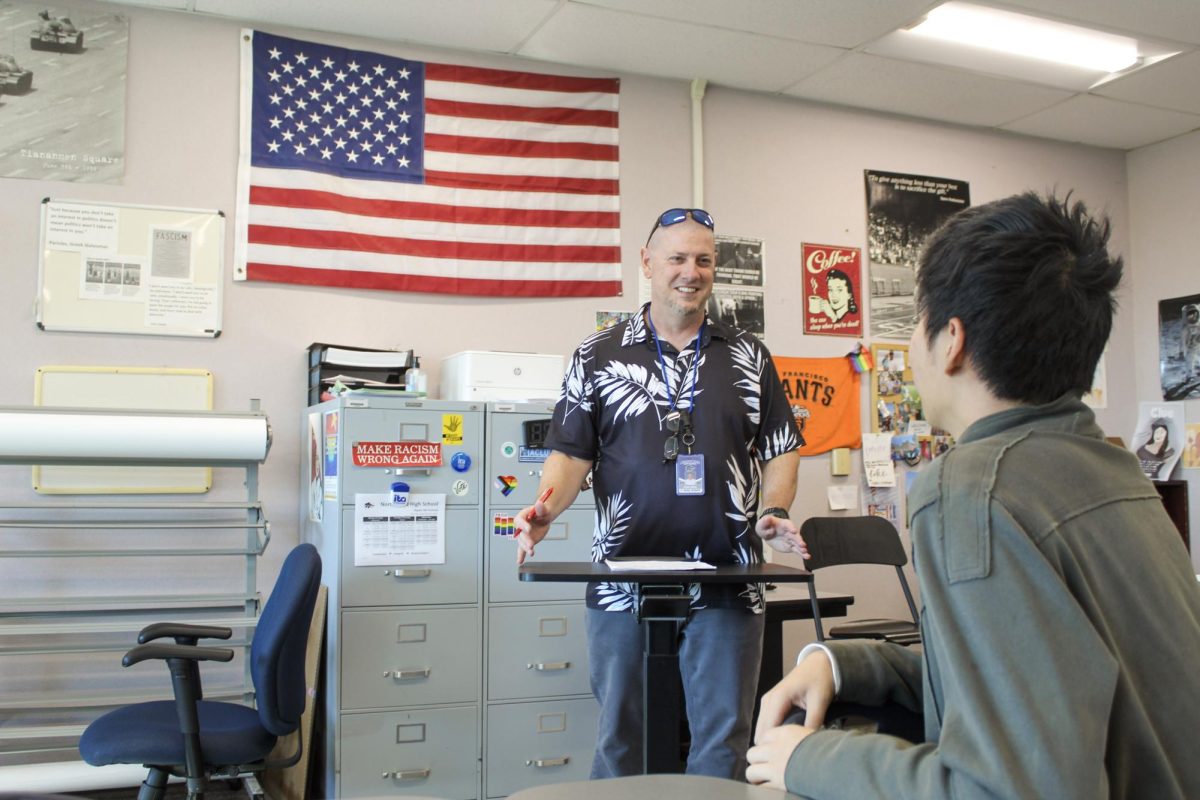

The Irvine Teachers Association has been holding productive conversations with IUSD to provide assistance for special education teachers and is hopeful for positive reform. One barrier outside of the district’s control is a lack of federal funding.

While some argue that allocating additional funding towards special education would be too costly, if the federal government paid its share of districts’ per-pupil costs for special education as it pledged in the IDEA Act in 1975, the burden for local officials would be reduced. In fact, the federal government has delivered only about 10% of districts’ costs instead of the promised 40%.

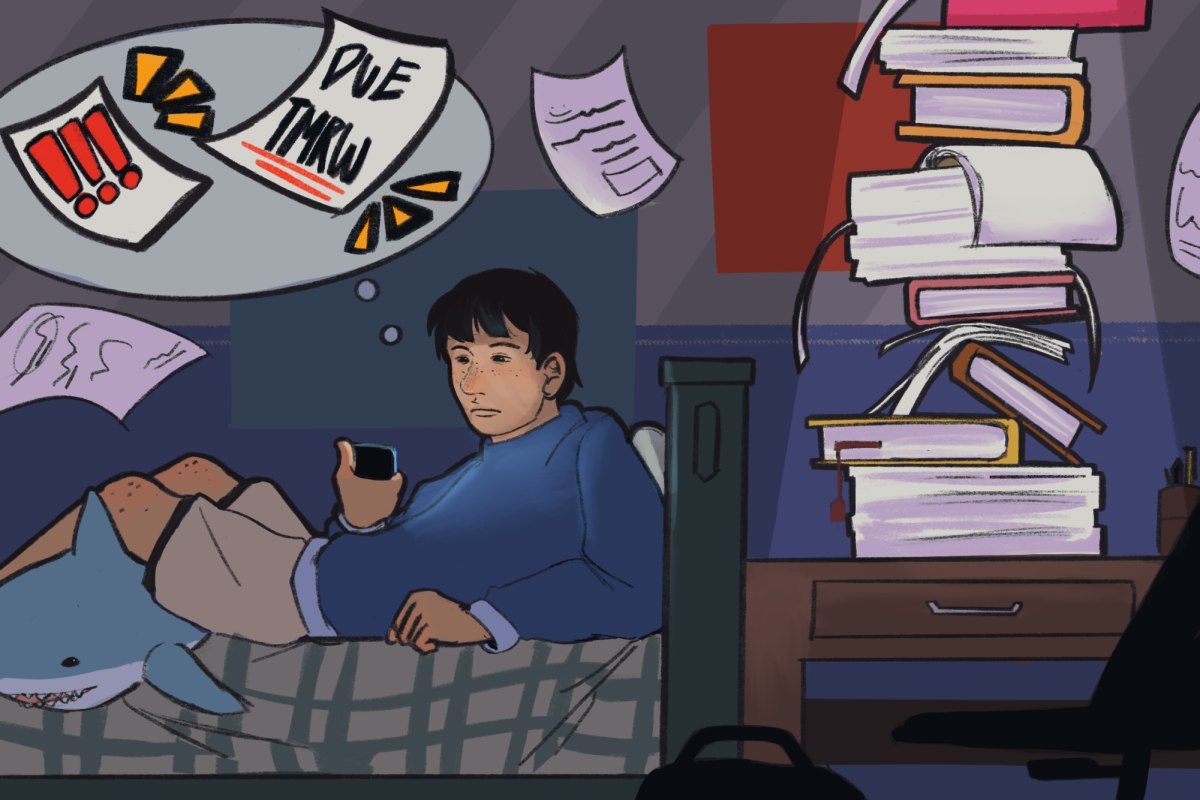

Meanwhile, many special education teachers put in extra unpaid hours in the summer, as lead teachers administer tests and plan meetings with staff, the principal and parents to create each student’s Individualized Education Plan.

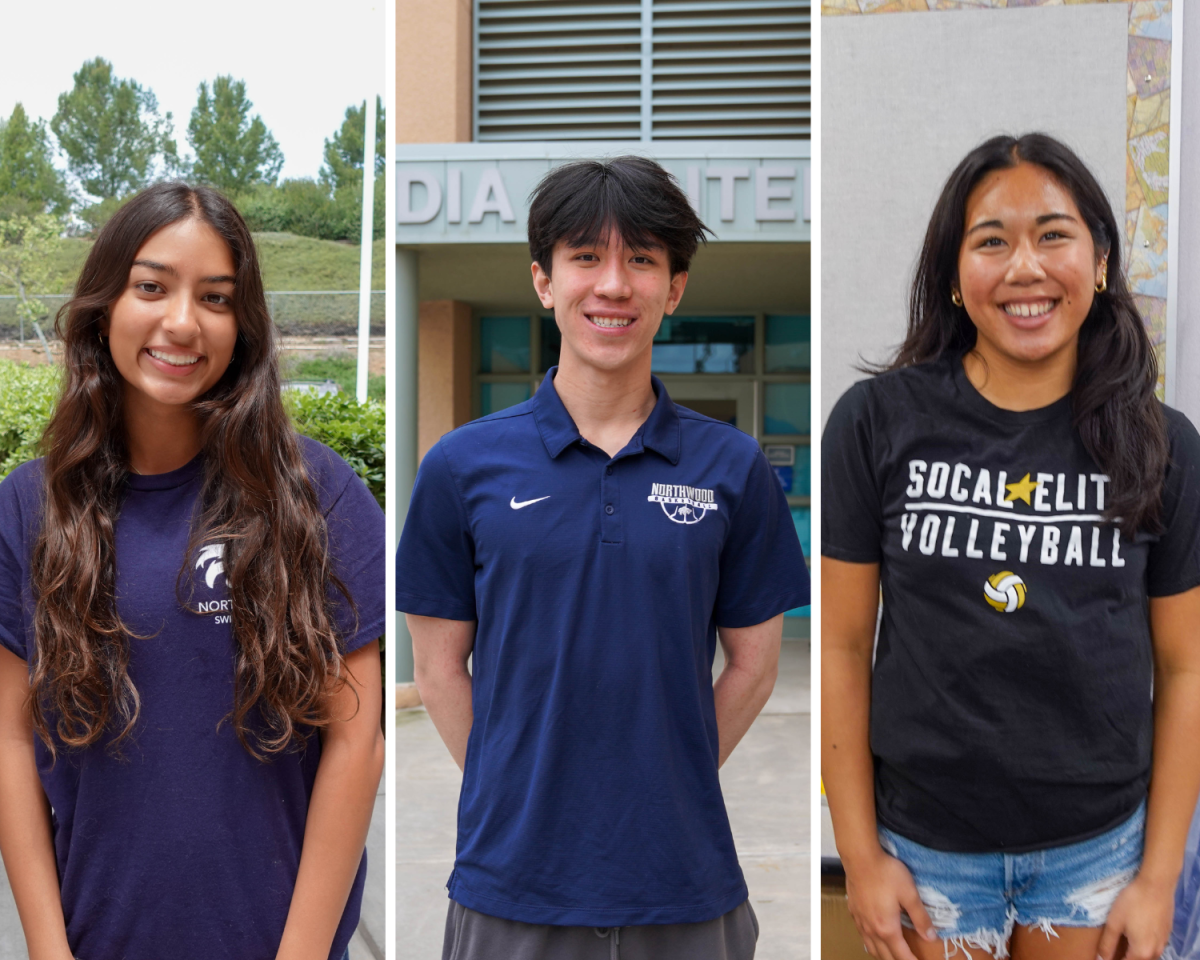

In addition, education specialists are in charge of managing 20-25 students at a time, numbers that IUSD and ITA hope to reduce.

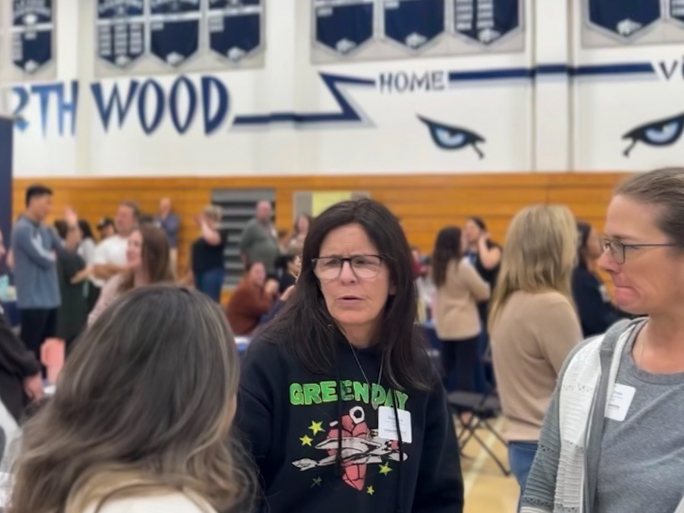

“Sometimes your case load will be quiet,” educational specialist Jennifer Petrosian said. “Other times, your case load blows up, and all of your kids need support. It’s always changing.”

Because contracts lack such language to compensate teachers, it has discouraged many from the profession. Due to the shortage, student-teacher ratios have risen, creating a difficult teaching environment for current educators.

When working beyond their contractual hours, teachers can request stipend pay from the district; however, because this is not spelled out within contracts, the district can legally refuse payment.

Similarly, education specialists often spend their own money on classroom materials specific to each student, which can become costly quickly, and, though they can apply for reimbursement, leadership changes or budget cuts could end this aid at any given time.

ITA officials are quick to point out that IUSD has been supportive of their efforts and has provided resources to assist special education teachers, and they simply hope to enshrine some of these protections in future contracts.

The issue of funding could be solved by passing the IDEA Full Funding Act, supported by over 20 senators and 60 house members, which would gradually increase funding nationally for disabled students by 1.2% a year until schools are funded the promised 40% by the federal government.

With this in place, IUSD could amend contracts to ensure that the special education department is better supported without placing strain on the district’s budget.

Everyone is entitled to fair education regardless of their needs, and without adequate contracts for teachers to encourage them into the profession, that equitable support is not there.

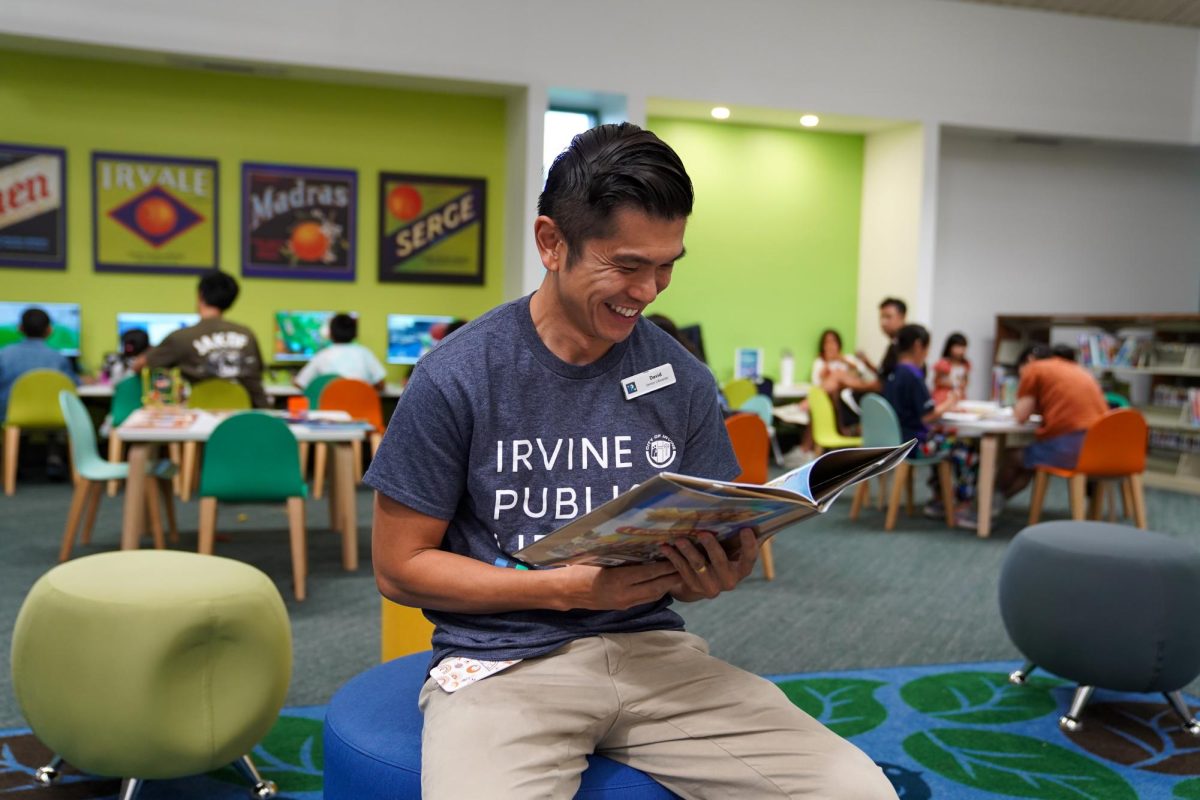

Several nonprofit organizations are currently campaigning to increase funding for IDEA, such as The National Center for Learning Disabilities. Also, others provide teachers with classroom essentials, such as the nonprofit organization DonorsChoose.

But, ultimately, private financial assistance is not enough to solve the funding crisis or protect teacher careers. It’s clear that teachers are paying the price, whether it is with their money or their time.

Action must be taken to permanently legitimize funding promises made to special education teachers.