Coverage-gate: the gatekeeping problem

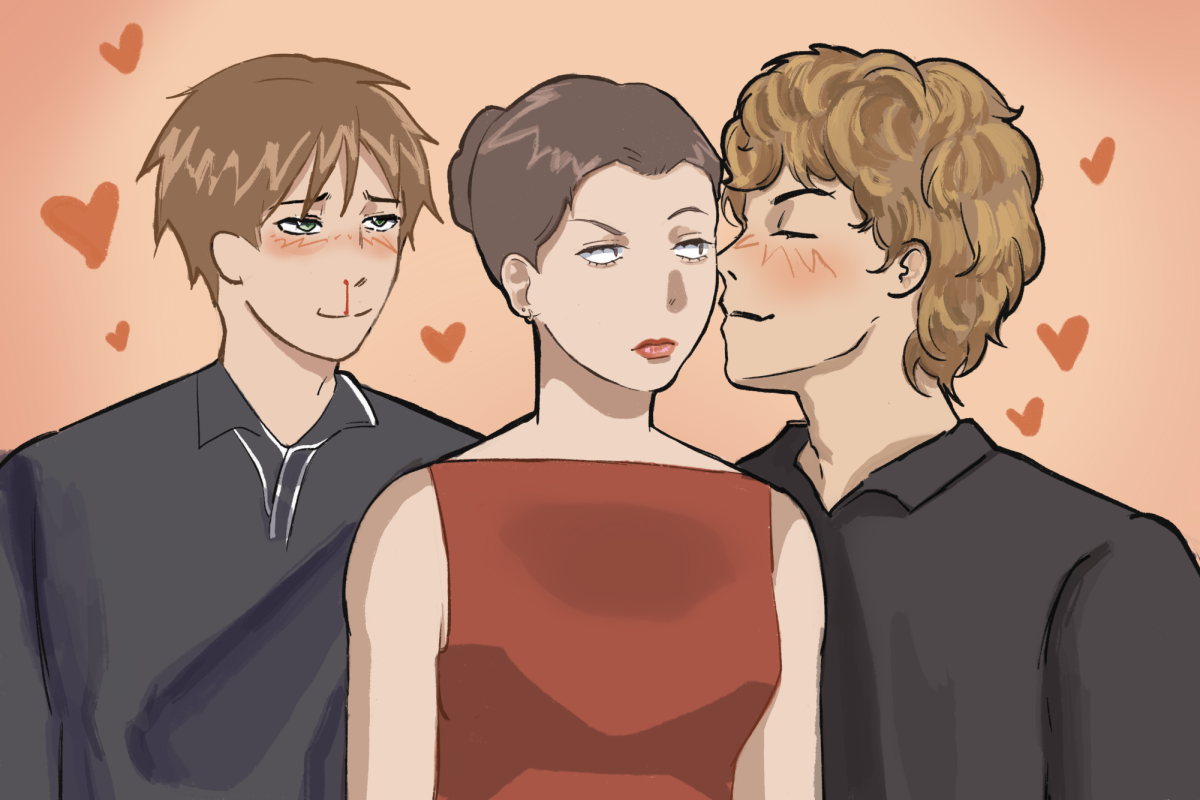

DESPIERTA (WAKE UP): Chileans protest for a new socio-economic order.

December 16, 2019

The Hong Kong protests have been one of the biggest stories in the news for several months. A quick search for “Hong Kong protest” in the New York Times for the past week yields 191 results (at the time of writing), and for good reason too. As protestors violently fight in support of the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement to protect their democratic liberties and autonomy, they face rubber bullets and tear gas from riot police. Over 2,000 thus far have been arrested and at least 10 have died since the riots began in June.

A similar violent protest has also been going on for six weeks over increased metro fares in Chile. In less than a month, over 2,000 have been arrested and at least 24 people have died in a crackdown of authority. Police have left several blinded by rubber pellets and hosed down crowds with water cannons. A search for “Chilean protest” on the New York Times for the past week yields 92 results (at the time of writing), far fewer than Hong Kong despite both being similarly controversial, violent and timely. This drastic difference is an example of gatekeeping: the unequal coverage of stories caused by corporate news outlets favoring viewership over holistic understanding.

The political and economic relations of different nations significantly change how news outlets cover events. In the U.S., most large news outlets support western business interests and downplay others. Therefore, a democratic protest against a communist economic rival like China is more valuable to media outlets than revolts against Chile’s U.S.-backed democratic government. Hong Kong matters more. While it makes sense for news outlets to cover what seems more impactful, that doesn’t mean that we should disproportionately favor certain news stories.

We can see this in the first few paragraphs of the New York Times article “Hong Kong Police Shoot Protester Amid Clashes” describing a police officer’s attack on a protester in vivid detail.

“The officer then tackles the protester he shot,” the article reads. “The protester is seen lying quietly on the ground, surrounded by what appear to be pools of his own blood.”

Take another New York Times article titled “‘Chile Woke Up’: Dictatorship’s Legacy of Inequality Triggers Mass Protests,” which mentions government responsibility in the crisis and makes sure to cover President Sebastián Piñera’s attempts to “restore order” and “quell the protests” early on. Although perspectives on these protests span the whole spectrum, articles on Hong Kong spend more time criticizing the police while articles on Chile carefully paint the public as a frustrated mob.

This pick-and-choose nature of gatekeeping is not unique to the New York Times, or even other U.S.-based news outlets. An article on the Hong Kong protests from the South China Morning Post, a Hong Kong-based news outlet, comments that “police do not believe anyone was hit” by rubber rounds (as if that justifies firing the rounds) and that the “police express utmost condemnation in the rioters’ flagitious act of assaulting police officers.” This stance continues throughout the article as it takes every opportunity to defend the riot police, quite opposite to what we see in the New York Times; the South China Morning Post is expectedly more inclined to avoid censorship for criticizing its government’s police force.

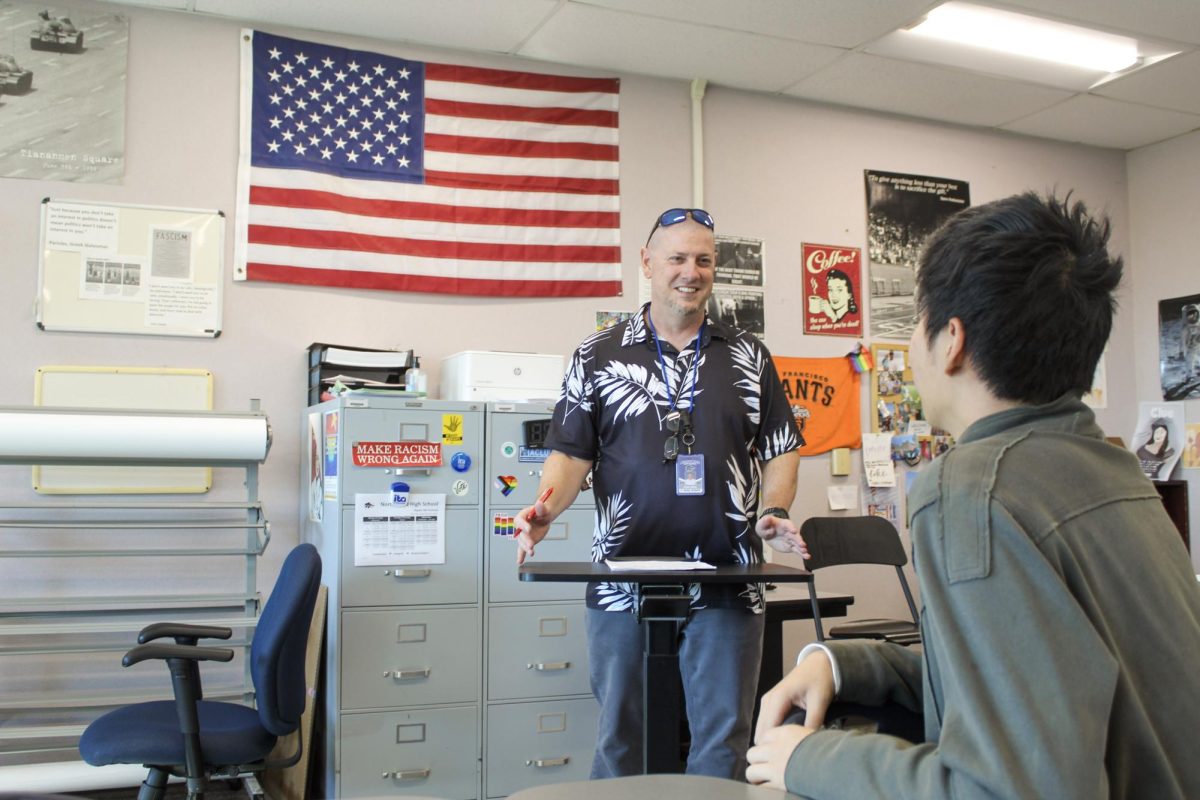

Gatekeeping is dangerous because it distorts our collective understanding of current events. The media is considered the “fourth estate” because it is the foundation for the opinions of the populace that inform how we interact in our social, political and economic spheres. At its worst, a misguided understanding can fuel unnecessary conflict due to misunderstandings per location. As such, the journalistic ethics and unbiased coverage are among central principles that we learn in Beginning Journalism at Northwood.

It is worth noting that this only covers the discrepancies between the New York Times’ coverage of protests in Hong Kong and Chile and could be criticized for cherry-picking sources. However, with thousands of articles on these topics, citing examples of articles from all the different news outlets would be impossible; as such, a more focused analysis of a popular reputable source like Times most clearly paints the picture of gatekeeping in media. But some quick exploration of the various media outlets and their articles will reveal similar results. There is far less coverage of Chile. It is also worth noting that gatekeeping does not only occur with these protests; the Hong Kong and Chile protests only happened to be a convenient basis of comparison.

Proper media coverage should practice meticulous journalism that actively seeks out conflicting perspectives above the “if it bleeds, it leads” mentality. Spending more time to output quality, well-researched information serves the purposes of journalism far more effectively than outputting excessively shallow information that suits a convenient narrative. As an audience, recognizing that these media outlets are not infallible is the first step. Actively seeking out alternative sources, such as independent journals, foreign news sources or academic journals, allows for a more holistic view of undercovered events. This brings attention to important problems, which puts pressure on wrongdoers, accelerates activism and paves the way for collaborative solutions. We should be aware of significant events around the globe, whether or not they appeal to our narrative. The people involved in the riots in Hong Kong are devoted to a cause with just as much value as those involved in Chile.