Just a quick consensus to make sure we’re all on the same page: racism is bad, yes? So is sexism, homophobia and all of the other excuses humans have come up with to treat each other terribly. Then why does it feel like our campus has recently taken a turn in the other direction?

A “microaggression,” coined by Black psychiatrist Chester Pierce, refers to subtle, often unconscious actions or statements motivated by bias, which, while not overt enough for marginalized communities to directly address, still have real and lasting impacts as thinly veiled forms of discrimination.

Although some people may roll their eyes at another new word to call someone ignorant, words have power. Labeling these prejudices reassures minorities that they are not alone in the shared experience of being made to feel uncomfortable, disrespected and even humiliated by those who don’t understand what it’s like to constantly toe the line of being an outsider.

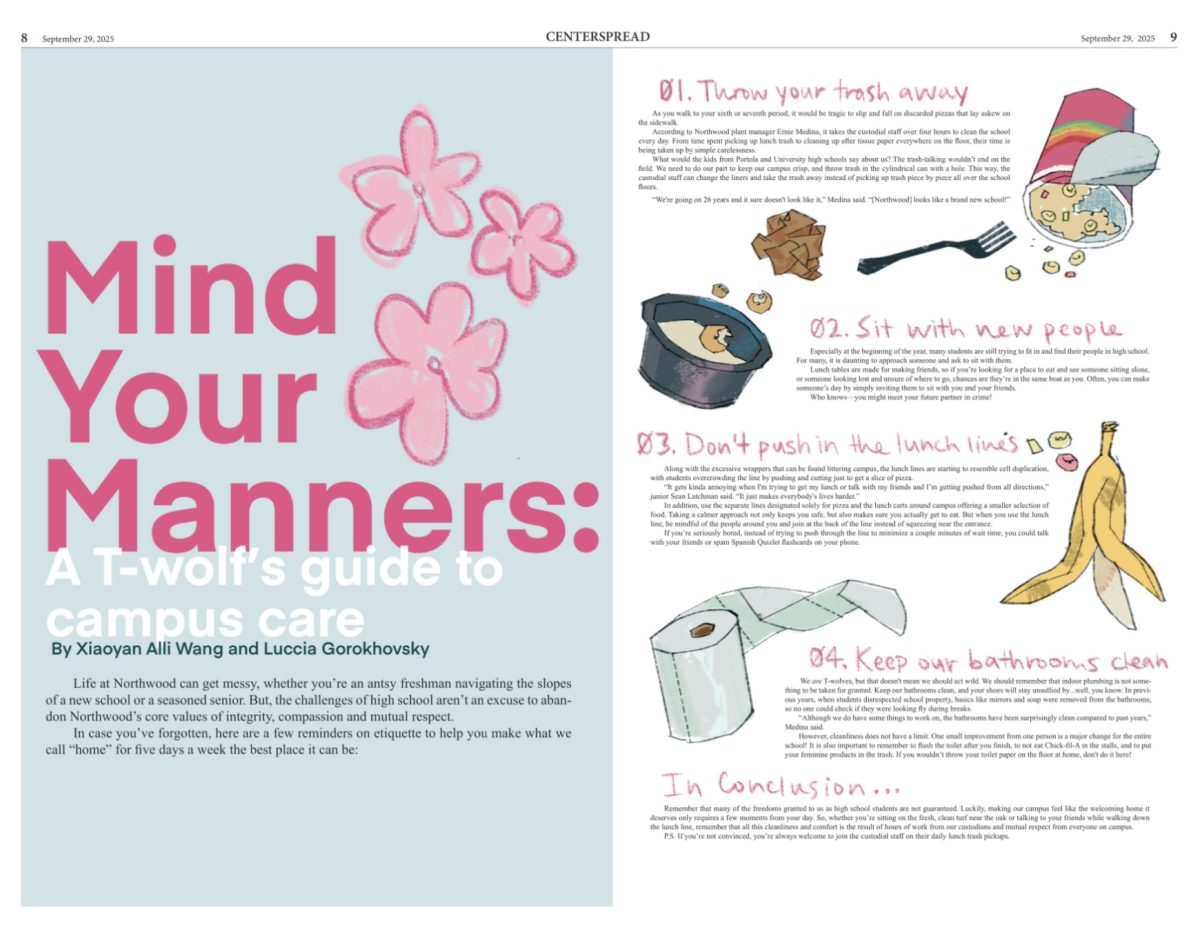

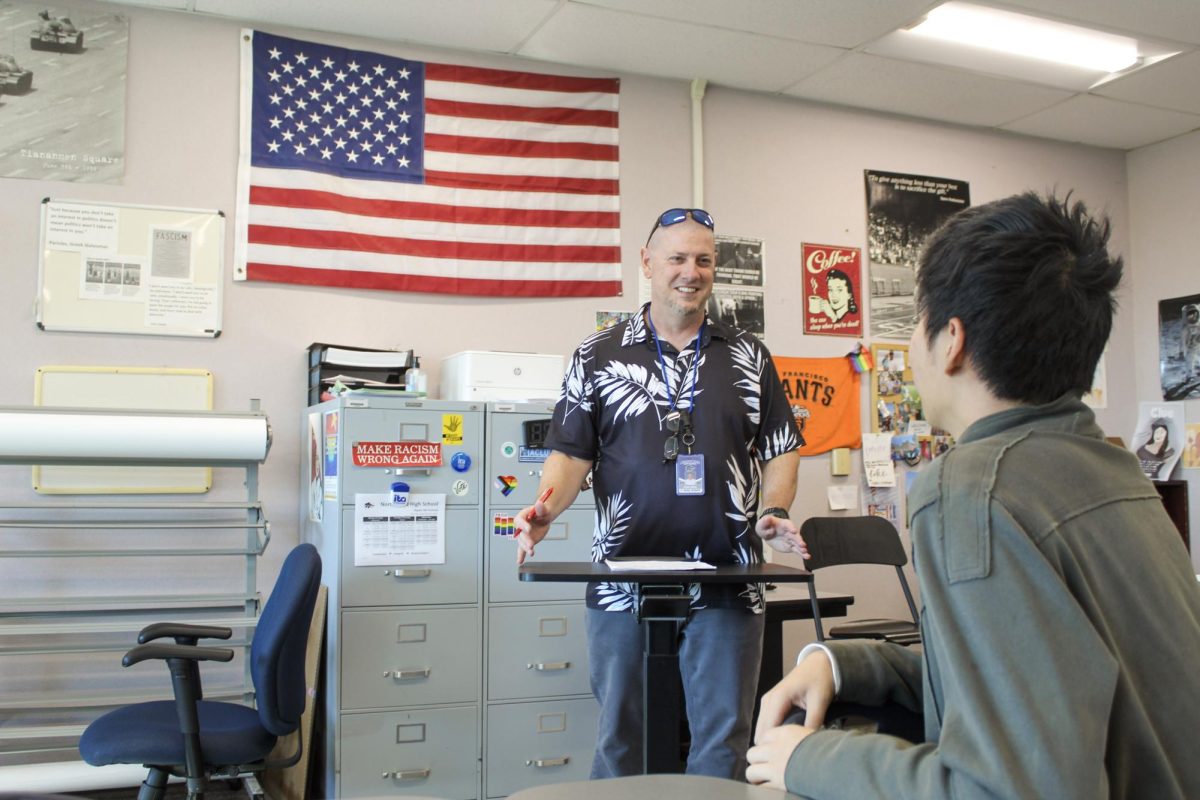

While most Northwood students would agree that these behaviors hold no place on our campus, it’s hard to ignore the troubling signs that suggest otherwise—just a walk by The Oak during a passing period raises the question of whether we’ve been truly upholding an anti-discriminatory mindset.

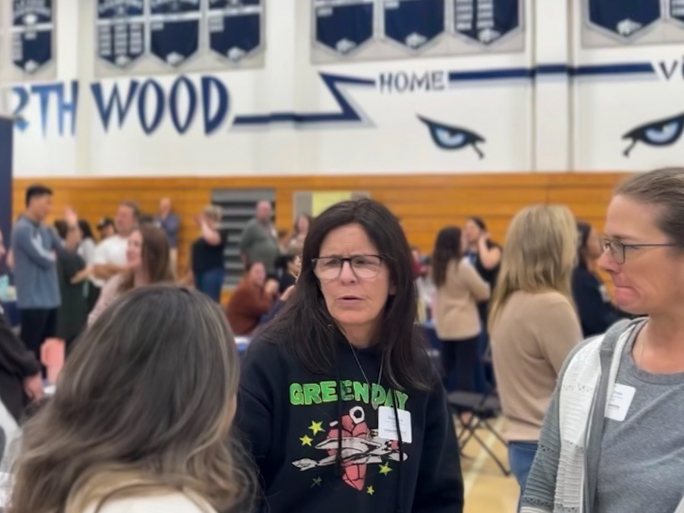

“Kids do report that they feel active discrimination, microaggressions, things like that,” principal Leslie Roach said. “We were hearing a lot more uses of derogatory language, like outside or during lunchtime.”

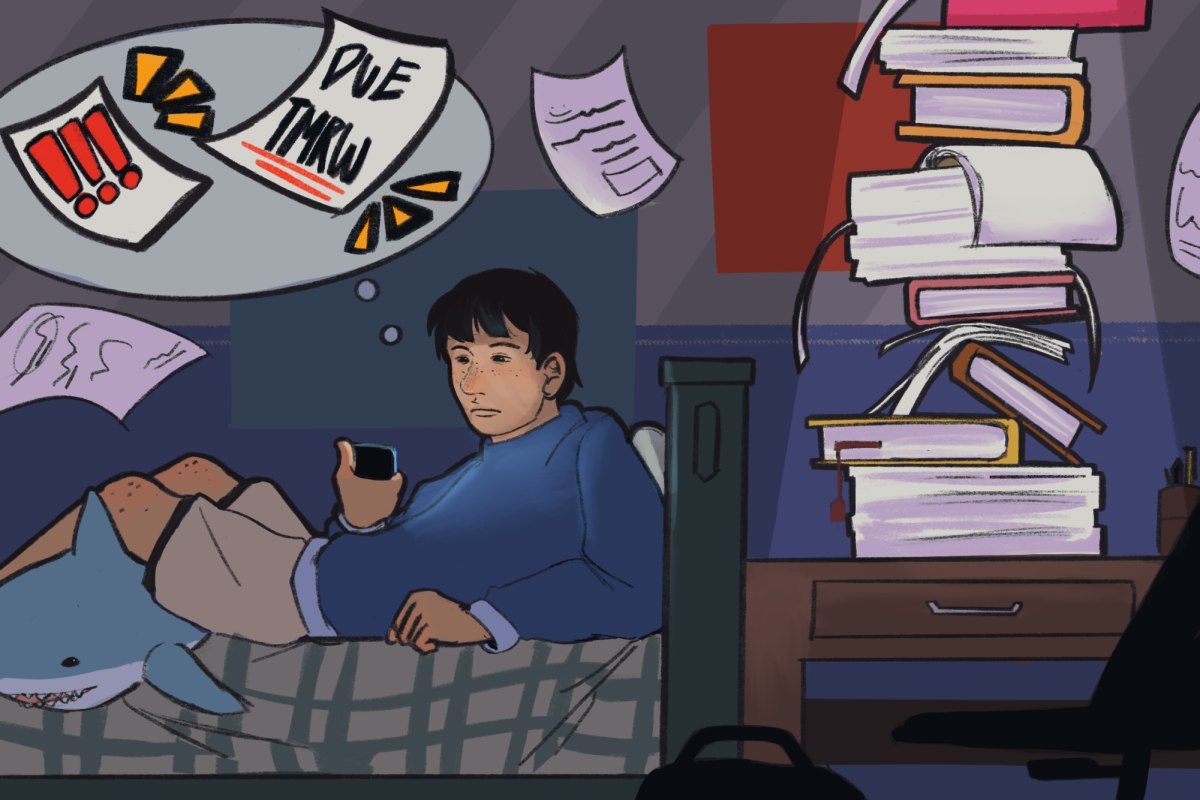

One factor contributing to this trend is the rise of slur usage in digital spaces—not by the perpetrators of the historic weaponization of these words, but by the targeted groups. As a part of the effort to push back against systemic discrimination, minorities have been “reclaiming” this language and removing its originally malicious intentions. However, this trend, along with the rise of dark humor, has led many in younger generations to forget about the harm that certain words can still cause, even when used jokingly.

Let’s put on the long-forgotten empathy hats from our primary education and think about some recent additions to our lexicon from social media. When we call a friend “acoustic” to mock their behavior, what are we saying to people with Autism Spectrum Disorder who have only just gotten people to stop saying the R-slur? When we call girls “bops,” what does it say about how we reduce the value of women down to their sexuality?

“I think it sometimes comes out of kids thinking they’re being funny,” Roach said. “But it’s derogatory towards race, gender, sexual orientation, all of the things that people feel they can say because they don’t feel it’s that big of a deal, or they’re just kidding.”

As students sharing a campus and citizens of the world, our greatest responsibility is to use our influence to stop our peers from contributing to harmful actions and encourage self-reflection. Often, simply asking someone to repeat the derogatory comment can be enough to make them realize the weight of their words.

Equally important is holding ourselves accountable: we must actively work to be more mindful of our language and its impact. The hope is that, as we mature and interact with the world as adults, we’ll better understand the tangible impacts that our actions have on our surroundings—but until then, we just have to help spark this enlightenment faster.