Fast fashion and the ethics of the clothing industry

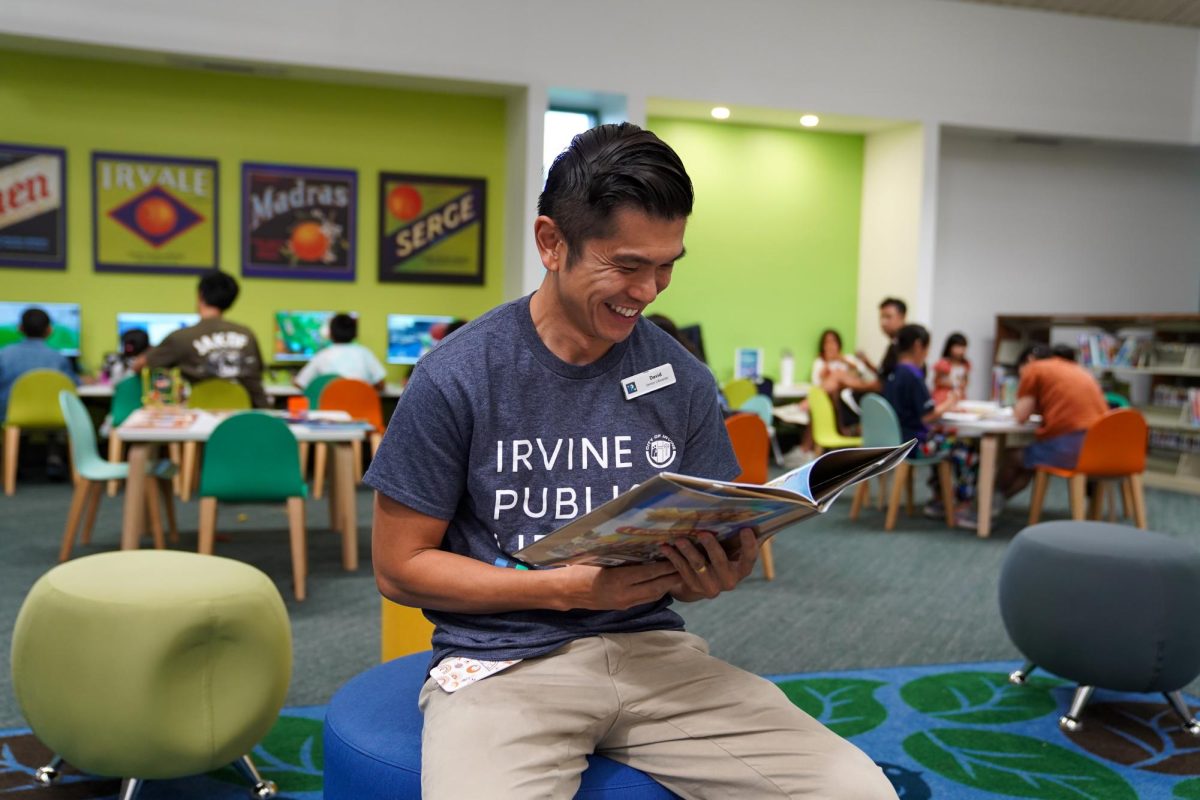

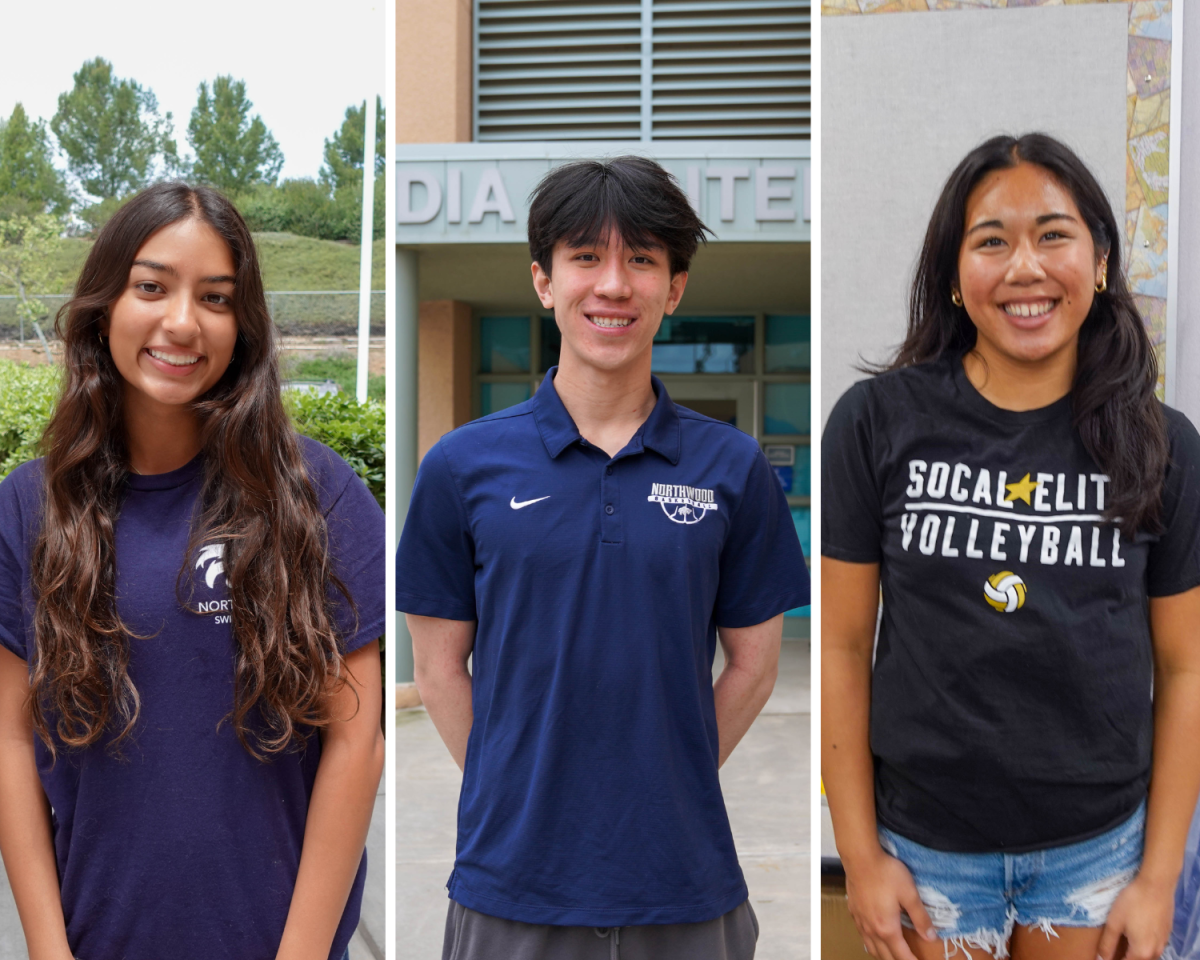

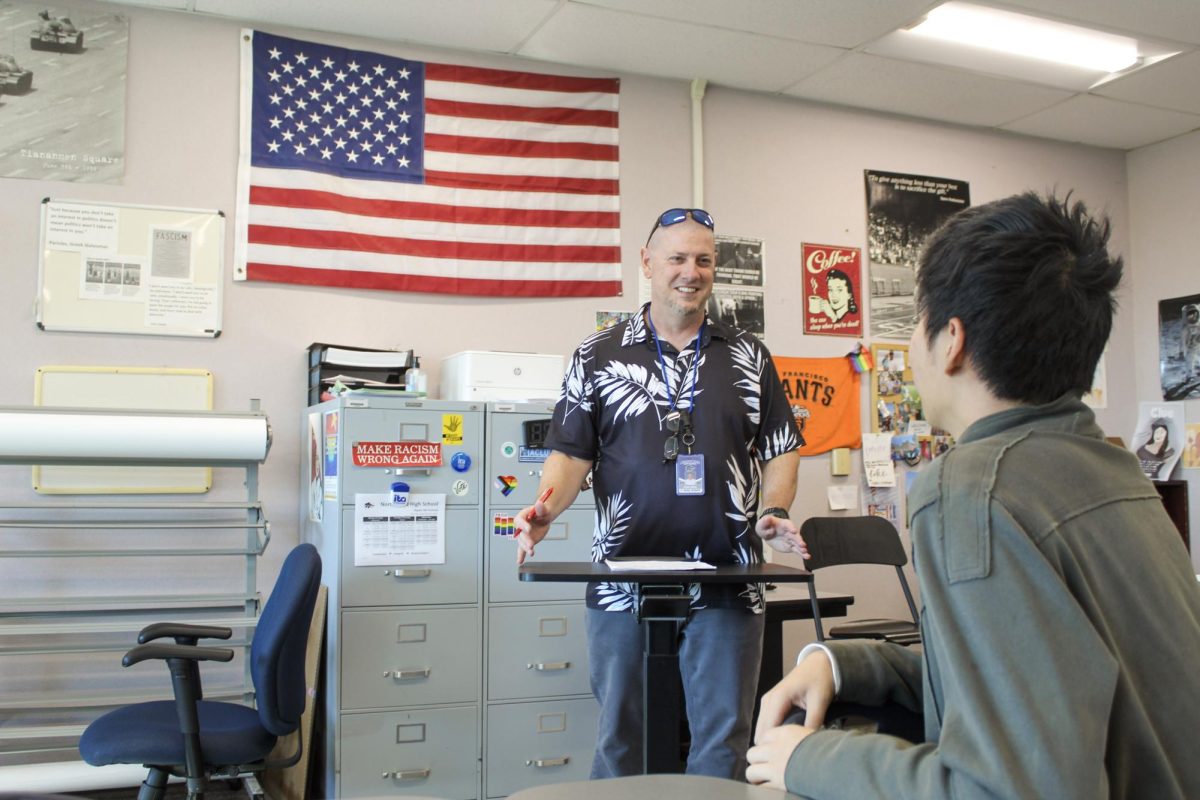

THE DEVIL WEARs POLYMERS: Senior Ally Chao shops at Cotton On.

October 28, 2019

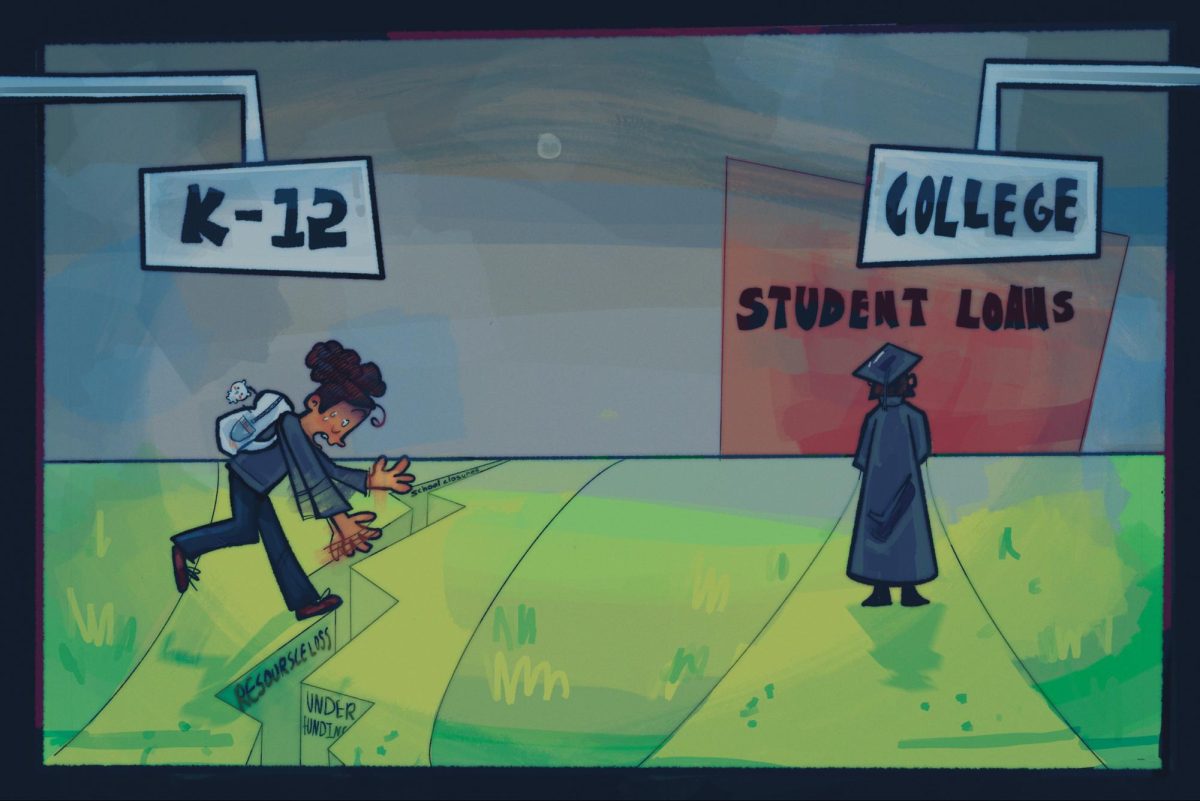

Fast fashion, by definition, is inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends. In real terms, it is the blatant exploitation of disadvantaged workers and an already crumbling environment in order to curb a few additional charges under the guise of “free market” capitalism.

Beginning in the 1990s, fast fashion started as a way to accelerate the turnaround time on seasonal collections. It started mainly due to an increased interest in fashion as well as a higher spending power on the part of consumers. To appease consumer appetites, companies began outsourcing the production of their pieces to third world countries, where production is cheaper and more efficient than it is domestically.

But what makes it cheaper? The blatant exploitation of workers in third world countries. Most companies use forced and/or child labor. In both undeveloped and developing countries, labor laws are known to be rather lax, akin to those we had here in the U.S. during the Market Revolution, the period of industrialization in early America. These laws are so lax that they basically permit any and every human rights violation in the book because there’s no one to represent the labor force. This allows corporations to create “sweatshops” around the world, where they can pay their “workers” little to no money whatsoever and no one bats an eye.

The truth of it is, fast fashion is a disease that began in the early ‘90s and spread all over the world, eroding human rights everywhere, even in countries that claim to have protective labor laws. For example,

Forever 21, which recently filed for bankruptcy, was a huge perpetrator of this system of “business,” taking advantage of what is known as the underground workforce of Los Angeles, according to the Los Angeles Times. The company spent most of its run paying workers $6 per hour, a wild human rights’ abuse. Yet, this is still a lot better than sweatshops in third world countries, like those run in Sri Lanka by Beyónce, where women were being paid 68 cents per hour for 60 hour weeks, according to an investigative report run by The Sun.

Furthermore, according to Vox, based on a study conducted by Quantis, “apparel and footwear production currently accounts for 8.1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, or as much as the total climate impact of the entire European Union.”

This is largely because corporations finding cheaper alternatives almost always leads to rapid overproduction. But excessive unnecessary materials are not the only things that weigh on the environment. The other most obvious source of waste is the fact that most brand-name companies burn the leftover pieces from out-of-date collections, rather than recycling or reselling them. And, while straight-up burning clothes is a practice most often restricted to luxury brands, retail brands aren’t much better about the clothes they don’t sell.

According to Redress, companies will use any number of processes to get rid of their unsold pieces— dumping them on “secondary” markets or destroying local businesses by flooding retail-branded clothes at lower prices into lower-income communities, to name a few—but rarely will any company recycle their pieces. Recycling fabric is a costly practice, given that current technology has yet to figure out how to fully recycle synthetic fabric, so companies often opt-out to avoid footing the bill.

The good news is that we as consumers hold the greatest amount of power in this equation. By choosing to be more conscious about where we spend our money and being vocal about why we’re opting out of certain stores, we can put an end to fast fashion a lot easier than we think. Fast fashion is not a necessary evil— the world ran without it for most of history— but rather an easy way for companies to save a dime through exploiting cheap labor, which means there is a world of fashion without it. Apps like Good on You, which give brands “sustainability ratings” based on their carbon footprint, their treatment of people and animals, and whether they are making strides to reform the fashion industry, are available to download across platforms. These grassroots organizations do the heavy lifting for you, so the next time you are at Irvine Spectrum Center, you can be more cautious of your consumption, how it affects the planet and those inhabiting it.